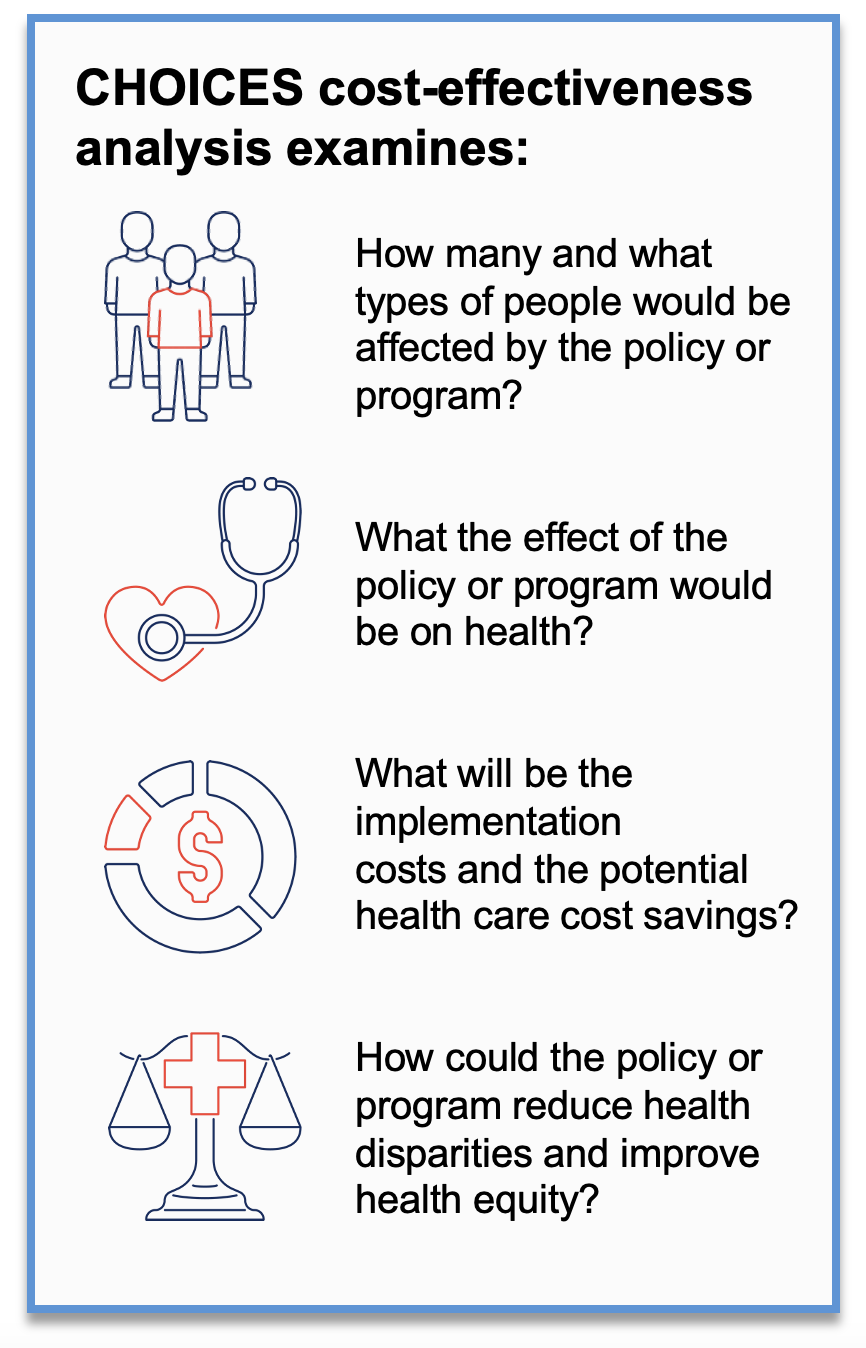

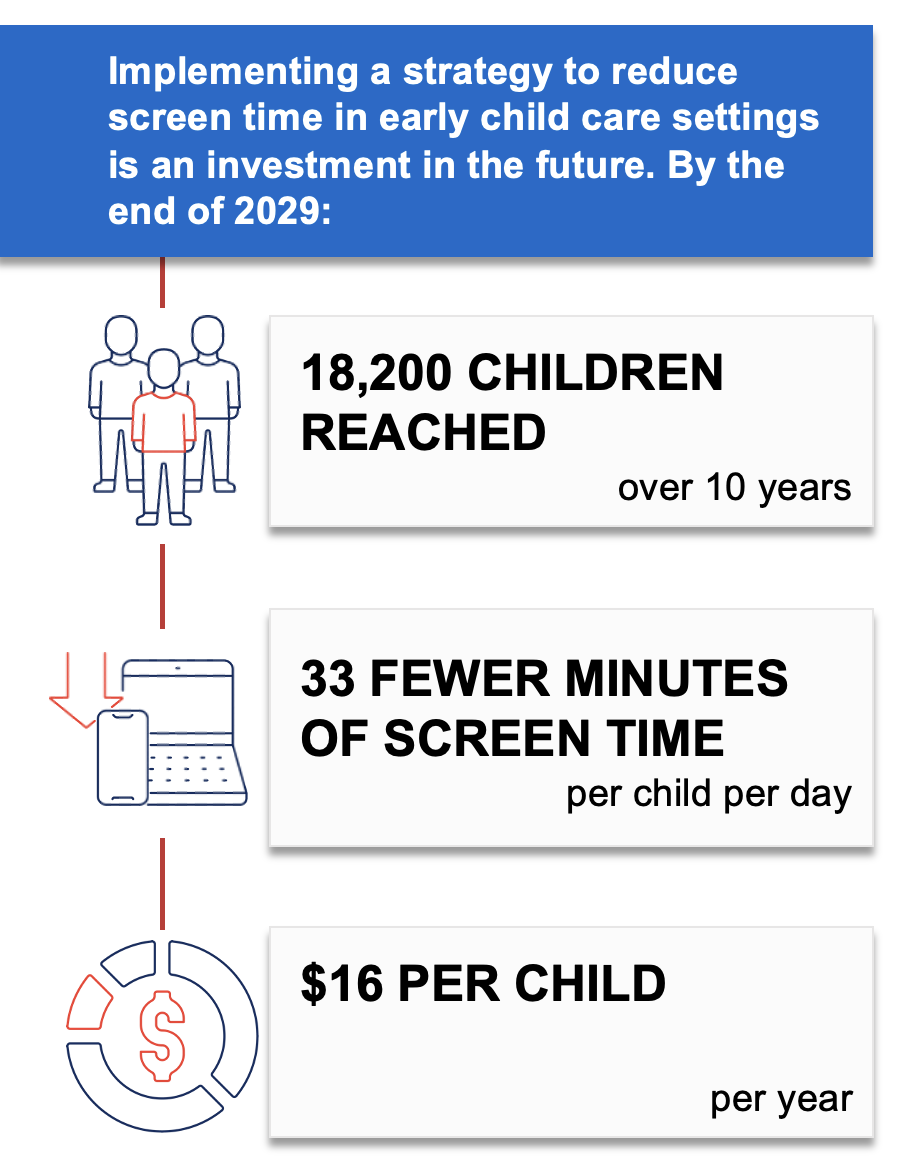

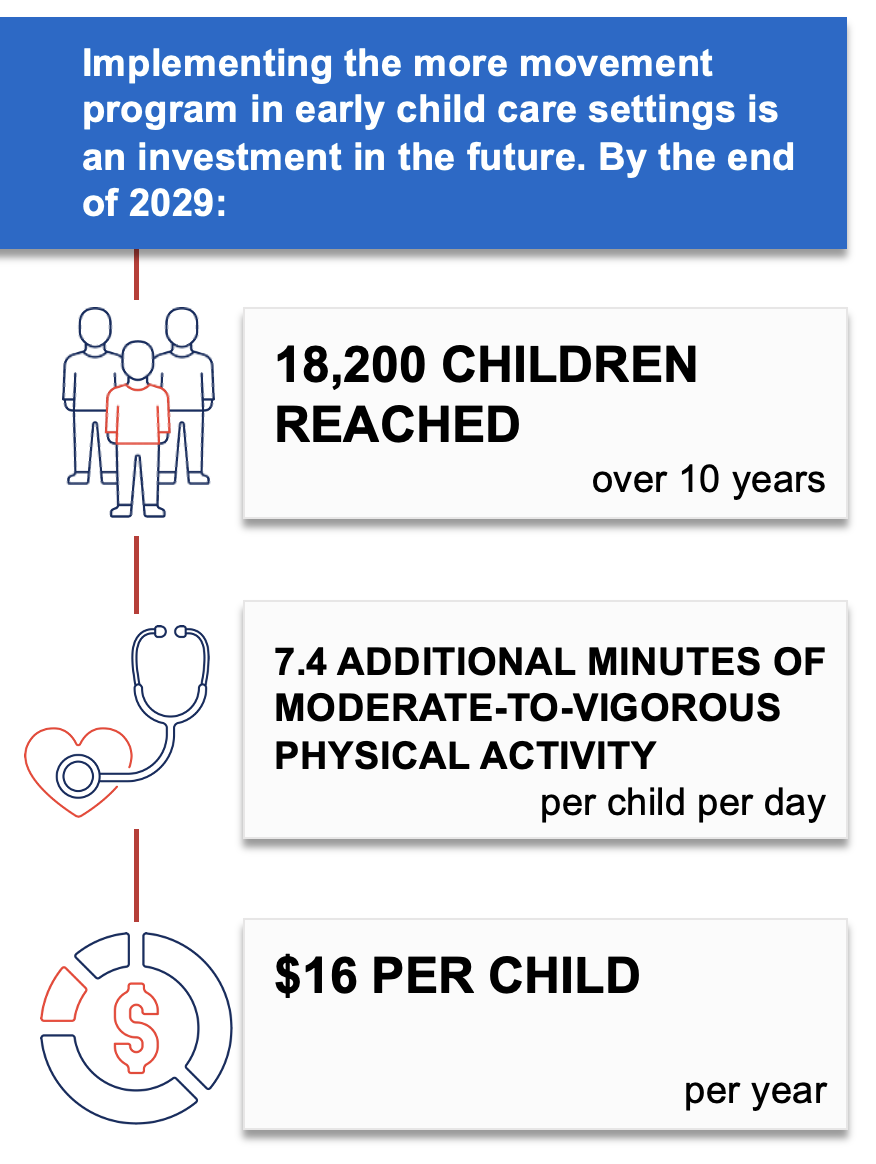

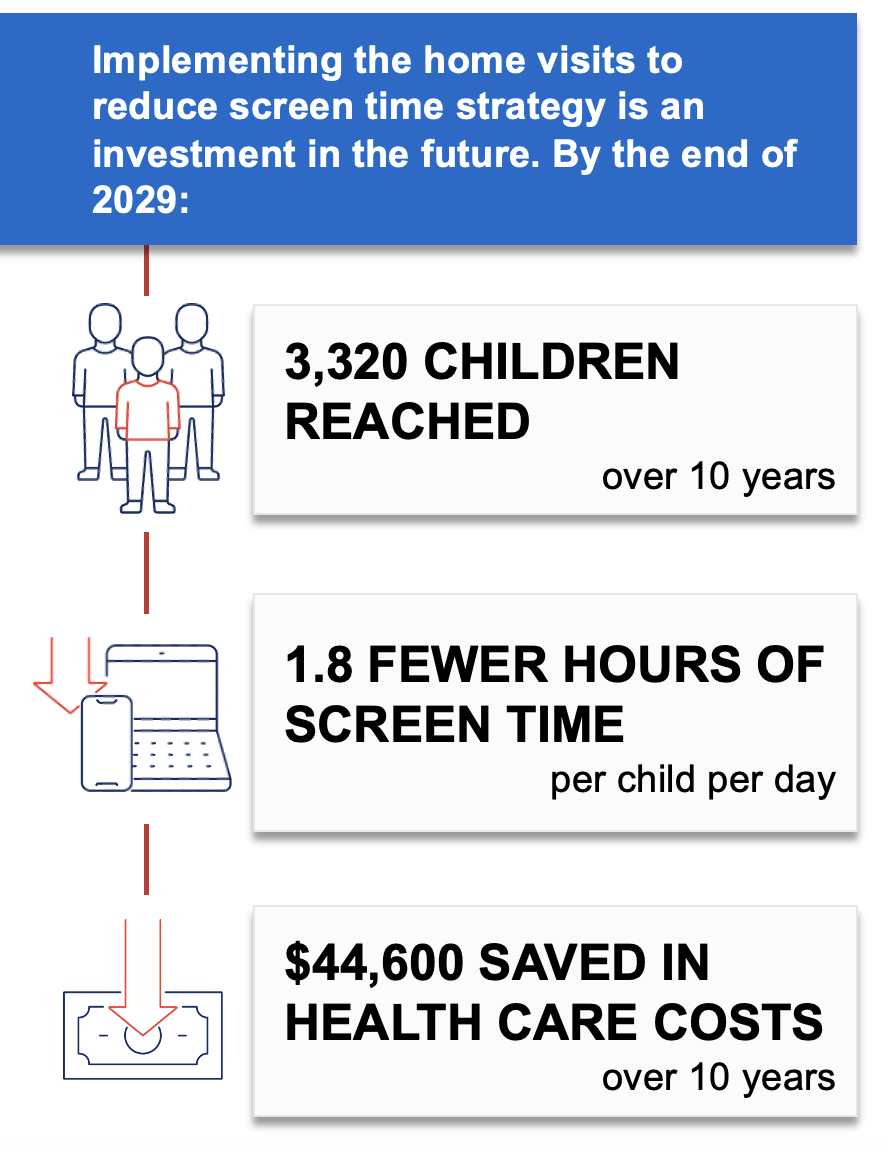

In this coffee chat hosted by the CHOICES Community of Practice, Dr. Steven Gortmaker, Principal Investigator of the CHOICES Project at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, highlights the new features available in the Action Kit 2.0, including more detailed information on costs and health equity impacts. Dr. Gortmaker also discusses how this information can be helpful for planning and prioritization purposes to ensure responsible investments to improve child health, nutrition, physical activity, and health equity.

View the resource round-up from this coffee chat