The information in this brief is intended only to provide educational information.

A version of this brief was published in May 2022. This brief was updated in February 2023 to reflect revised projections for Boston’s population.

This brief summarizes a CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership model examining a strategy to reduce the amount of screen time viewed at home by young children in Boston, MA. Community health workers would provide counseling and resources on strategies to limit children’s screen time to children and families who participate in home visiting programs.

The Issue

In 2017, three in 10 first graders in Boston had overweight or obesity.1 Access to healthy foods, beverages, and opportunities to participate in regular physical activity are key priorities for communities in supporting children growing up at a healthy weight. However, not all families have access to the same resources.

Limiting children’s screen time is also a high priority for communities.2 Food companies use television to market unhealthy foods and drinks to children, which can increase children’s food intake and their risk for excess weight gain.3 Moreover, food companies have disproportionately marketed fast food and sugary drinks to Black and Hispanic youth4 and children from lower income households watch more screen media than their peers,5 putting them at greater risk for unfavorable health outcomes.

Helping families manage screen time can promote a healthy weight and advance health equity. Home visiting programs engage community health workers to improve health behaviors and reduce the risk of chronic diseases for families with children. Home visiting programs specifically support children who are exposed to conditions that could negatively impact their health.6

About the Home Visits to Reduce Screen Time Strategy

This strategy supports the Boston Public Health Commission’s goal of preventing obesity and chronic disease using a health equity lens while also building and maintaining partnerships with home visiting programs across Boston. Through professional development trainings opportunities, community health workers would learn ways to support families and children in limiting their screen time. During a home visit, community health workers would share the importance of appropriate screen time limits and provide strategies and tools for families to use, including a screen time management device. Integrating this strategy through existing home visiting programs could help more children manage their screen time and grow up at a healthy weight.7

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes over a 10-year time horizon (2020-2030) of implementing the home visits to limit screen time strategy with the costs and outcomes associated with not implementing the program.

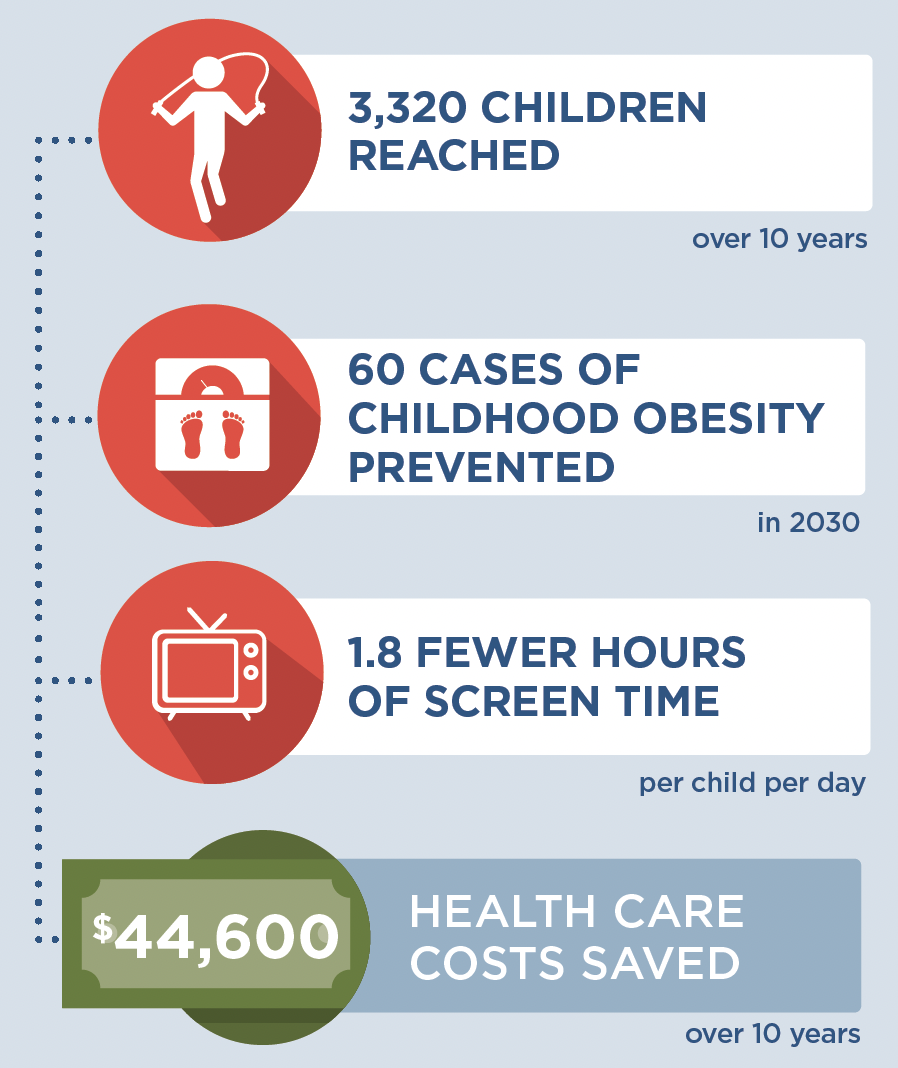

Implementing the home visits to reduce screen time strategy is an investment in the future. By the end of 2030: |

Conclusions and Implications

Incorporating counseling and providing resources to limit screen time through existing home visiting programs could reach 3,320 children ages 4-7. Over 10 years, we project that children whose families participated in the program would watch nearly two fewer hours of screen time per day, on average. This strategy could also prevent 60 cases of childhood obesity in 2030, saving $44,600 in health care costs related to excess weight over 10 years. It would cost $540 per child.

Community health workers play an important role in building healthier communities and promoting health equity. By training and equipping 119 community health workers annually by ensuring that everyone has access to what they need to grow up healthy and strong, this strategy could help reach those families and children that may be at higher risk of having or developing obesity. Children in households with low income could see greater health benefits from this strategy.7

In addition to promoting healthy weight, this strategy may also benefit children in other ways. Too much screen time can negatively impact children’s sleep and social wellbeing.8 Providing children and their families with strategies to move away from their screens allows for more time for developmentally appropriate activities like reading and active play. Strategies families can use to limit online video viewing and mobile device use may be particularly important as screen time from these sources has increased dramatically in recent years.5

Working with community health workers in Boston’s existing home visiting programs will help families build a foundation for overall health and wellbeing. These preventive strategies play a critical role in helping children establish healthy habits early on in life.

References

-

School Health Services, Dept of Public Health. Results from the Body Mass Index Screening in Massachusetts Public School Districts, 2017. School Health Services, Dept of Public Health; 2020. Accessed Feb 22, 2022. https://www.mass.gov/doc/the-status-of-childhood-weight-in-massachusetts-2017

-

Healthy People 2030: Building a healthier future for all. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office of the Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed Feb 4, 2022. https://health.gov/healthypeople

-

Russell SJ, Croker H, Viner RM. The effect of screen advertising on children’s dietary intake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(4):554-568. doi:10.1111/obr.12812

-

UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. Fast Food Advertising: Billions in spending, continued high exposure by youth. 2021. Fast Food Fact, UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. https://www.fastfoodmarketing.org/media/FACTS%20Summary%20FINAL%206.15.pdf

-

Rideout V, Robb MB. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Age Zero to Eight. 2020. Common Sense Census. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-kids-age-zero-to-eight-2020

-

Duffee JH, Mendelsohn AL, Kuo AA, Legano LA, Earls MF. Early Childhood Home Visiting. Pediatrics. Sep 2017;140(3). doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2150

-

Epstein LH, Roemmich JN, Robinson JL, et al. A randomized trial of the effects of reducing television viewing and computer use on body mass index in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. Mar 2008;162(3):239-45. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.45

-

Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. Sep 21 2011;8:98. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-98

Suggested Citation:Carter S, Bovenzi M, Sabir M, Bolton AA, Reiner JR, Barrett JL, Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL. Boston, MA: Home Visits to Reduce Screen Time {Issue Brief}. Boston Public Health Commission, Boston, MA, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; February 2023. For more information, please visit www.choicesproject.org |

A version of this brief was published in May 2022. This brief was updated in February 2023 to reflect revised projections for Boston’s population.

The design for this brief and its graphics were developed by Molly Garrone, MA and partners at Burness.

This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the Boston Public Health Commission through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only. This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.