A map of the United States, showing all the places where CHOICES has worked to evaluate childhood obesity prevention programs and policies.

Topic: Healthy Eating

Cost-Effectiveness of Strategies to Reduce Obesity Among Young Children

A research brief detailing which strategies provide the most value for money spent to reduce early childhood obesity.

Brief: Supporting Healthy Food and Beverage Choices in Afterschool Programs in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

The information in this brief is intended only to provide educational information.

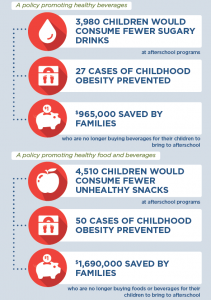

This brief summarizes a CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership model examining the potential impacts of a healthy snack policy in afterschool programs that already provide snacks through the National School Lunch Program or the Child and Adult Care Food Program.

The Issue

All children deserve the opportunity to grow up at a healthy weight. If current trends in childhood obesity continue, most of today’s children will have obesity at age 35.1 The health care costs of treating obesity-related conditions in adulthood were $147 billion in 2008.2 Snacks account for 25% of total calorie intake among most U.S. children and are frequently composed of sweet foods and sugar-sweetened drinks,3 beverages that increase the risk of excess weight gain.4 Promoting healthy food and beverage choices in afterschool programs is one opportunity to improve children’s diets and potentially reduce childhood obesity.5

In Allegheny County, nearly 10,000 children attend an afterschool program that typically allows participants to bring in snacks that they can consume during the program. When children bring in their own snacks to afterschool programs, those snacks are often less healthy than snacks served within federal reimbursable meal programs.6

About a Healthy Snack Policy

A policy that does not allow children to bring in their own snacks to afterschool programs and only offers healthy food and/or beverage choices that are part of federal reimbursable meal programs could support good nutrition. Snacks refer to both foods and beverages. In Allegheny County, UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, and Allegheny Partners for Out-of-School Time work with 120 sites across the county through Healthy Out-of-School Time and Quality Campaign. The majority of these sites (117) serve snacks though federal reimbursable meal programs, but allow children to bring in their own snacks. These sites could benefit from adopting a healthy snack policy. Activities to support adoption of this policy would include training site directors, who would in turn train program staff. During the academic year, Healthy Out-of-School Time and Quality Campaign site coordinators would provide technical assistance to support policy adoption.

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes of adopting a healthy snack policy in 117 Healthy Out-of-School Time and Quality Campaign afterschool programs over 10 years. Programs could adopt either a policy that does not allow children to bring in sugary drinks or a policy that does not allow children to bring in either sugary drinks or their own food to afterschool programs.

Implementing a healthy snack policy could support good nutrition and save families money. By the end of 2027: |

Conclusions and Implications

Adopting a healthy snack policy could promote better health for children in afterschool programs and save families money. For some programs, it may be more feasible to adopt a policy addressing sugary drinks only. Clear evidence links sugary drink consumption to excess weight gain.4

We estimate that providing the training, technical assistance, communication, coordination, and monitoring in afterschool programs to support the adoption of a healthy snack policy that only addresses sugary drinks would cost $53,500 over 10 years. It could also result in $965,000 in savings for families ($243 per child) who are no longer purchasing beverages for their children to bring to afterschool. Those children who regularly bring sugary drinks to afterschool programs and attend Healthy Out-of-School Time and Quality Campaign afterschool programs that adopt a healthy snack policy could reduce sugary drink consumption by 10 ounces per day on those days they attend programming. In addition, 27 cases of childhood obesity could be prevented in 2027 and $53,900 in obesity-related health care costs could be saved. Afterschool programs adopting a healthy snack policy can support healthy nutrition habits for children and lay a foundation for better health.

References

- Ward Z, Long M, Resch S, Giles C, Cradock A, Gortmaker S. Simulation of Growth Trajectories of Childhood Obesity into Adulthood. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017 Nov 30;377(22):2145-2153.

- Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual Medical Spending Attributable To Obesity: Payer-And Service-Specific Estimates. Health Affairs. 2009;28(5).

- Wang D, van der Horst K, Jacquier E & Eldridge AL. Snacking among US children: patterns differ by time of day. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2016; 48(6), 369-375.

- Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84(2):274–88.

- Khan LK, Sobush K, Keener D, Goodman K, Lowry A, Kakietek J, et al. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2009;58(RR-7):1–26.

- Kenney EL, Austin SB, Cradock AL, Giles CM, Lee RM, Davison KK, Gortmaker SL. Identifying sources of children’s consumption of junk food in Boston after-school programs, April-May 2011. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014 Nov 20;11:E205

Suggested Citation:Pagnotta M, Hardy H, Burry K, Flax C, Barrett J, Cradock A. Allegheny County: Supporting Healthy Food and Beverage Choices in Afterschool Programs [Issue Brief]. Allegheny County Health Department, Pittsburgh, PA, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; November 2019. |

This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the Allegheny County Health Department (ACHD) through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only.

Brief: Best Practice Guidelines for Healthy Childcare in Detroit

The information in this brief is intended only to provide educational information.

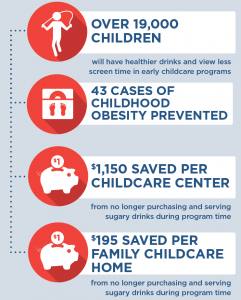

This brief summarizes a CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership model for Best Practice Guidelines for Healthy Childcare in Detroit, MI. We assume a proportion of licensed programs would voluntarily adopt guidelines to eliminate sugary drinks and limit screen time. Participation rates are based on the number of programs voluntarily achieving 3+ star ratings from Great Start to Quality Program.1

The Issue

All children deserve the opportunity to be healthy. However, if current trends in childhood obesity continue, most of today’s children will have obesity at age 35.2 The health impacts and health care costs of treating obesity-related conditions in adulthood, such as heart disease and diabetes, cost $147 billion in 2008.3 However, research shows that avoiding sugary drinks and viewing less TV can help kids grow up at a healthy weight.

Early childcare programs are essential partners in supporting healthy habit development. Approximately 11,000 2-5 year-olds attend licensed childcare centers and family homes in Detroit.4 Providing training and technical assistance on guidelines to eliminate sugary drinks and limit non-educational screen time to 30 minutes per week would positively impact the children attending licensed childcare programs.

About the Best Practice Guidelines for Healthy Childcare Model

Best Practice Guidelines for Healthy Childcare would be put forth by the Detroit Health Department. The United Way provides professional development for early childcare professionals and would offer new voluntary training and technical assistance opportunities to early childcare providers. In turn, providers would implement the guidelines in their programs. The guidelines would encourage early childcare programs to not serve sugary drinks and to reduce non-educational television time to 30 minutes per week during program time. We estimate that 62% of centers and 30% of family childcare homes would voluntarily adopt the guidelines.1

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes over a 10-year time horizon (2017-2027) of implementing Best Practice Guidelines for Healthy Childcare vs. not implementing the guidelines.

Implementing Best Practice Guidelines for Healthy Childcare is an investment in the future and would save early childcare programs money. By the end of 2027, the model projects: |

Conclusions and Implications

Every child deserves a healthy start in life. This includes ensuring that all children in childcare have less exposure to beverages with added sugar and no nutritional value and have less exposure to screen time. Implementing Best Practice Guidelines for Healthy Childcare has the potential to reach 19,400 children ages 2-5 years in licensed childcare programs in Detroit. These children would consume fewer beverages with added sugar and view less screen time. In particular, children in family childcare homes would watch 2.3 fewer hours of screen time daily if the guidelines are met. This intervention would cost $107,000 to implement, though childcare program providers would save money when they are no longer serving sugary drinks. Overall, the CHOICES model estimates that there is a 97% chance that the intervention would be cost-saving. That is, it could save more due to the reduction in spending associated with serving sugary beverages than it may cost to implement.

The first few years of childhood can be an important time to promote healthy lifestyle behaviors. Implementing Best Practice Guidelines for Healthy Childcare could lay the foundation by ensuring that all children in childcare settings drink beverages that promote their health and have less exposure to screen time.

References

- Great Start to Quality Participation Data, July 1 2019. https://www.greatstarttoquality.org/great-start-quality-participation-data Accessed July 17 2019.

- Ward Z, Long M, Resch S, Giles C, Cradock A, Gortmaker S. Simulation of Growth Trajectories of Childhood Obesity into Adulthood. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017 Nov 30;377(22):2145-2153.

- Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual Medical Spending Attributable To Obesity: Payer-And Service-Specific Estimates. Health Affairs. 2009;28(5).

- Per previous estimates that 79% of children in day care are ages 2-5 years old out of the 0-5 year old population

Suggested Citation:Hill AB, Mozaffarian RS, Barrett JL, Cradock AL. Detroit: Best Practice Guidelines for Healthy Childcare [Issue Brief]. Detroit Health Department and United Way for Southeastern Michigan, Detroit, MI, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; December 2019. The design for this brief and its graphics were developed by Molly Garrone, MA and partners at Burness. |

This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the Detroit Health Department through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only. Funded by The JPB Foundation. Results are those of the authors and not the funders.

WIC Food Package Changes: Trends in Childhood Obesity Prevalence

A CHOICES study analyzed changes in childhood obesity prevalence among children participating in WIC both before and after food package changes were enacted in 2009, and found that obesity prevalence among children participating in WIC has been decreasing since the 2009 changes.

Daepp MIG, Gortmaker SL, Wang YC, Long MW, Kenney EL. WIC Food Package Changes: Trends in Childhood Obesity Prevalence. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5):e20182841.

The aim of this study was to evaluate if the changes made to the foods that could be purchased through the U.S. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in 2009 had an impact on childhood obesity.

In 2009, the lists of foods that could be purchased with WIC vouchers (known as the WIC food packages), which includes basic food categories, were updated to better align with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The new package, still in use today, provided extra cash allowances for fruits and vegetables, cut the previous juice allowance in half, required low-fat or skim milk for 2-4 year olds, reduces cheese, and required whole-grain instead of refined-grain products (among other changes).

Earlier studies showed that this shift had resulted in significant changes in WIC participants’ diets and in lowering the amount of calories they consumed. The Centers for Disease Control showed that there had been some declines in childhood obesity prevalence among WIC participants in recent years.1 However, there had not yet been a direct test of whether the WIC package change may have catalyzed a turn-around in childhood obesity rates among WIC participants.

Using state-specific obesity prevalence data for 2-4 year olds participating in WIC from 2000 to 2014, the researchers estimated the annual trend in obesity prevalence across states, and then tested whether that trend significantly changed after the WIC package revision in 2009, adjusting for changes in demographics.

The researchers found that, before the 2009 WIC food package change, the prevalence of obesity across states among 2-4 year olds participating in WIC was growing 0.23 percentage points annually. However, after 2009, this alarming trend switched direction. Instead, the prevalence of obesity across states among 2-4 year olds participating in WIC started decreasing by 0.34 percentage points annually.

“Our study suggests that, in addition to its critical role in reducing the burden of food insecurity and improving nutrition among young children in low-income families, WIC also can help promote healthy weight,” says co-author Erica Kenney, CHOICES Co-Investigator and Professor of Public Health Policy in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “This is especially encouraging given that over half of all infants born in the U.S. are eligible for the program – there is a real opportunity here to have a positive impact on childhood obesity.”

These results suggest that the 2009 WIC food package change likely helped to reverse the rapid increase in obesity prevalence among WIC participants observed before the food package change, helping set the millions of young children who benefit from WIC on a path toward a healthier weight.

References

- Pan L, Freedman DS, Sharma AJ, Castellanos-Brown K, Park S, Smith RB, Blanck HM. Trends in Obesity Among Participants Aged 2-4 Years in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children – United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Nov 18;65(45):1256-1260. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6545a2

Brief: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) Intervention in West Virginia

The information in this brief is intended for educational use only.

This brief provides a summary of the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership simulation model of integrating Key 2 a Healthy Start, West Virginia’s implementation of Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC), into the state’s Tiered Reimbursement system, which provides subsidy incentives to child care centers meeting quality standards.

The Issue

Over the past four decades, childhood obesity has tripled.1 In WV, obesity rates in 2-4 year old WIC participants increased from 14% up to 16.4% in 2014.2 WV was one of four states that experienced increasing rates in this young population. Now labeled as an epidemic, health care costs for treating obesity-related health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes range from $147 billion to $210 billion per year.3 While multiple strategies are needed to reverse the epidemic, emerging prevention strategies directed at children show great promise for addressing the epidemic.4 A large body of evidence shows that healthy eating, physical activity, and limiting sugary drinks and screen time helps kids grow up at a healthy weight.

In West Virginia, 41% of 2-5 year olds attend a licensed child care center. Licensed centers can offer healthy, nurturing environments for children. Tiered Reimbursement can encourage and empower centers to voluntarily improve nutrition, physical activity, and screen time standards while increasing financial incentives.

About Key 2 A Healthy Start

Key 2 a Healthy Start is based on NAP SACC, an evidence-based intervention for helping child care centers attain best practices regarding nutrition, active play, and screen time.5,6 The program enables child care directors and staff to complete self-assessments of their nutrition, active play, and screen time practices and receive training and technical assistance to implement changes that create healthier environments and policies. Integrating Key 2 a Healthy Start into West Virginia’s Tiered Reimbursement system would incentivize and support participation in the intervention and broaden its availability.

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes of integrating Key 2 a Healthy Start into Tiered Reimbursement over 10 years versus the costs and outcomes of not implementing the intervention. This model assumes that 44% of licensed child care centers will participate in Tiered Reimbursement and thus participate in Key 2 a Healthy Start.

Implementing Key 2 a Healthy Start in child care centers throughout West Virginia is an investment in the future: |

Conclusions and Implications

Every child deserves a healthy start in life. This includes ensuring that all kids have access to healthy foods and drinks and to be physically active, no matter where they live or which child care they attend. A state-level initiative to bring Key 2 a Healthy Start to West Virginia’s child care centers through the Tiered Reimbursement system could prevent 593 cases of childhood obesity in the last year of the model. Additionally, healthy child care environments and policies would be implemented for over 38,000 children.

For every $1.00 spent on implementing Key 2 a Healthy Start, a savings of $0.10 in health care costs is estimated. These results reinforce the importance of Key 2 a Healthy Start as primary obesity prevention. Implementing small changes early for young children can help them develop healthy habits for life, thereby avoiding more costly and ineffective treatment options in the future.

Evidence is growing about how to help children achieve a healthy weight. Programs such as Key 2 a Healthy Start are laying the foundation for healthier futures by helping child care centers create environments and policies that nurture healthy habits. Leaders at the federal, state, and local level should use the best available evidence to determine which evidence-based interventions hold the most promise for children to develop and maintain a healthy weight.

References

- Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents: United States, 1963-1965 through 2011-2012. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics, 2014.

- Pan L, Freedman DS, Sharma AJ, et al. Trends in Obesity Among Participants Aged 2-4 Years in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children – United States, 2000–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2016;65:1256–1260. DOI.

- Gortmaker SL, Wang YC, Long MW, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Barrett JL, Kenney EL, Sonneville KR, Afzal AS, Resch SC, Cradock AL. Three interventions that reduce childhood obesity are projected to save more than they cost to implement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015 Nov;34(11):1932-9.

- West Virginia Bureau of Children and Families (2015).

- Ward DS, Benjamin SE, Ammerman AS, Ball SC, Neelon BH, Bangdiwala SI. Nutrition and physical activity in child care: results from an environmental intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Oct;35(4):352-6.

- Alkon A, Crowley AA, Neelon SE, Hill S, Pan Y, Nguyen V, Rose R, Savage E, Forestieri N, Shipman L, Kotch JB. Nutrition and physical activity randomized control trial in child care centers improves knowledge, policies, and children’s body mass index. BMC Public Health. 2014 Mar 1;14:215.

Suggested Citation:Jeffrey J, Giles C, Flax C, Cradock A, Gortmaker S, Ward Z, Kenney E. West Virginia Key 2 a Healthy Start Intervention [Issue Brief]. West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, Charleston, WV, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; April, 2018. |

This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only.

Brief: Childcare Policies Can Build a Healthier Future in Philadelphia

The information in this brief is intended for educational use only.

In June 2017, Philadelphia’s Board of Health passed a resolution recommending that ECE (early childhood education) providers limit screen time and sweet drinks, including juice, for the children in their care.1

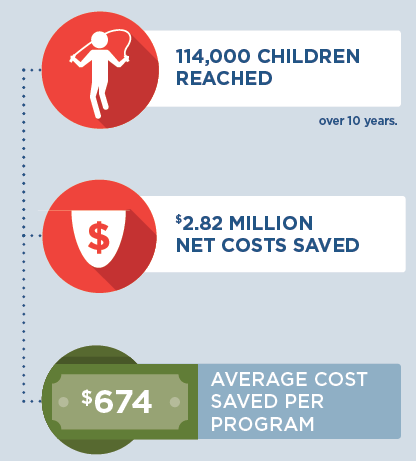

If all Philadelphia ECE providers implemented these voluntary recommendations, hundreds of children would see improved health outcomes, and $2.82 million could be saved over the next 10 years.

Analysis

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH) collaborated with a team of researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health2 to perform a cost-effectiveness analysis of policies to limit screen time and eliminate sweet drinks in early childhood settings. A cost-effectiveness analysis compares the health impact and health care cost savings resulting from implementing an initiative with maintaining the status quo. The analysis predicts how much would be spent or saved by implementing a policy or program.

PDPH and the Harvard Chan School called on local and national data and the expertise of partners3 to project costs and outcomes specific to Philadelphia’s ECE landscape. Projected costs, including training and technical assistance for ECE providers, would total $638,000 over 10 years. Projected savings, primarily from serving water instead of sweet drinks, would be $3.28 million.4 Over the same 10 year period, these changes would reach 114,000 children and prevent 279 cases of childhood obesity.

ECE Provider Savings

There are 1,661 licensed ECE providers in Philadelphia. Based on data PDPH collected from a sample of these providers, the Harvard researchers estimated the current frequency of serving sugary drinks and 100% juice in Philadelphia child care programs, average serving sizes, and average ounces served per day. They then multiplied the average ounces served per day by the price per ounce of each drink (from the USDA’s CNPP food price database). Finally, they adjusted for the fact that, since 100% juice can be reimbursed as “fruit” for the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), programs that participate in CACFP would incur costs to replace juice with whole fruit at breakfast or lunch and whole grains at snack; this analysis assumes that programs that do not participate in CACFP make the same substitutions.

These calculations yielded an average cost saving per child per day of about $0.013 for eliminating sugary drinks and $0.05 per child per day for eliminating 100% juice (that’s about $674 saved per year for the average center).

Many ECE providers in Philadelphia (including nearly 84% of centers) have already eliminated sugary drinks. Some (including nearly 18% of centers) have already eliminated 100% juice.4 Even so, if all licensed ECE providers in Philadelphia eliminated sugary drinks and 100% juice entirely, they (and their food vendors and CACFP sponsors) would save $3.28 million over 10 years. If centers that do not participate in CACFP replaced that juice with free water, these savings would increase to $4.89 million over 10 years.

|

Conclusions and Implications

Every child deserves a healthy start in life. Alarmingly, an estimated 33% of children born in 2000 and up to 50% of African American and Hispanic children will develop diabetes in their lifetimes.5 For many of these children, good nutrition (including fewer sweet drinks and less exposure to unhealthy food and beverage marketing online and on TV) can prevent or delay diabetes and other chronic conditions that are the leading causes of death and disability in our city.

Philadelphia’s licensed ECE providers serve around 40,000 children ages 2-5 each year. The Board of Health recommendations aim to support more providers in making small changes that will support healthier environments for all of these children and set them up for long, healthy lives.

The results of this cost-effectiveness analysis demonstrate the fiscal sense of the Board of Health’s recommendations to limit screen time and eliminate sweet drinks, including juice. The results reinforce the importance of investing in prevention efforts. Shortchanging prevention efforts can lead to more costly and complicated treatment options in the future, whereas teaching small changes to young children can help them develop healthy habits for life.

References

- City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health, Board of Health, Resolution on Childhood Obesity Prevention in Early Childhood Care, Approved June 8, 2017; http://www.phila.gov/health/pdfs/boardofhealth/Board%20of%20Health%20ECE%20Resolution%20Approved%20June%208%202017.pdf

The full recommendations state:

No sweetened drinks in early childhood settings

No fruit juice (including 100% juice) in early childhood settings

Water should be available, easily accessible to children throughout the day and offered with meals

Screen time for children aged 2 years and older limited to 30 minutes per week

No screen time for children under age 2 in early childhood settings - The Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health is working to help reverse the US obesity epidemic by identifying the most cost-effective childhood obesity interventions.

- Thank you especially to the Delaware Valley Association of Young Children, Mayor’s Office of Education, Public Health Management Corporation, and School District of Philadelphia.

- Full calculations are available from PDPH; contact Shannon Dryden at Shannon.Dryden@Phila.gov.

- Gregg EW et al Trends in lifetime risk and years of life lost due to diabetes in the USA, 1985-2011: a modeling study. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology 2(11) 867-874 downloaded from: http://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullTextImages?pii=S2213-8587%2814%2970161-5

Suggested Citation:Pharis M, Lawman H, Root M, Dryden S, Wagner A, Bettigole C, Mozaffarian, RS, Kenney EL, Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL, Giles CM, Ward ZJ. Philadelphia, PA: Childcare Policies Can Build a Better Future {Issue Brief}. Philadelphia Department of Public Health, Philadelphia, PA, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; December 2017. |

|

The design for this brief and its graphics were developed by Molly Garrone, MA and partners at Burness. This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the Philadelphia Department of Public Health through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only. Funded by The JPB Foundation. Results are those of the authors and not the funders. |

Brief: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) Intervention in New Hampshire

The information in this brief is intended for educational use only.

This brief summarizes a CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership simulation model in New Hampshire examining a potential strategy to expand child care providers’ access to the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (Go NAP SACC) by targeting the state’s largest providers via contracted training and technical assistance.

The Issue

Over the past three decades, more and more people have developed obesity.1 Today, nearly nine percent of 2-5 year olds have obesity.2 Now labeled as an epidemic, health care costs for treating obesity-related conditions such as heart disease and diabetes were $147 billion in 2008.3 While multiple strategies are needed to reverse the epidemic, emerging prevention strategies directed at children show great promise.4 A large body of evidence shows that healthy eating, physical activity, and less time watching TV helps kids grow up at a healthy weight.

In New Hampshire, 40% of 2-5 year olds attend licensed child care centers; 24% attend a large center or family child care program.5 Making NAP SACC more available can encourage and empower programs to voluntarily improve nutrition, physical activity, and screen time standards.

About NAP SACC and Expanding Access for NH Child Care Programs

Go NAP SACC is an evidence-based, trusted intervention that helps child care programs improve practices for nutrition, active play, and screen time and can reduce childhood obesity.6,7 Child care providers complete self-assessments of their nutrition, active play, and screen time practices and receive training and technical assistance to implement self-selected changes to create healthier environments. Increasing the number of provider slots offered through a contract with child care training and technical assistance specialists at Keene State College, managed by New Hampshire’s Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Public Health Services (DPHS), could broaden the current reach of the Go NAP SACC project, allowing more licensed child care programs to improve nutrition and physical activity policies and practices. Currently, Keene State works with 22 child care providers. Since 2010, over ninety licensed child care programs, caring for nearly 8,000 children, have participated in DPHS funded opportunities to improve 465 nutrition and physical activity policies and practices.

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes of expanding New Hampshire’s NAP SACC program led by partners at Keene State College over 10 years.

Implementing NAP SACC in New Hampshire’s largest child care programs is an investment in the future. By the end of 2025: |

Conclusions and Implications

Every child deserves a healthy start in life. This includes ensuring that all kids in child care have opportunities to eat healthy foods and be physically active, no matter where they live or where they go for child care. A state-level initiative to bring NAP SACC to New Hampshire’s largest child care programs by expanding its current opportunities could prevent over 600 cases of childhood obesity in 2025 and ensure healthy child care environments for 40,000 young children.

A separate model examined the potential for expanding access to Go NAP SACC via the state’s Quality Rating Improvement System, which is a single-tiered system referred to as Licensed Plus. While such an initiative could be a useful policy tool for creating sustainable access to Go NAP SACC for NH child care providers, the results of that model indicated that fewer children (12,000) would be reached and fewer cases of obesity prevented in 2025 (100) at a slightly higher cost per child ($81). The results of the two models suggest that New Hampshire’s current contracted strategy targeting the state’s largest providers may be more cost-effective. Results from both models reinforce the importance of investing in prevention efforts to reduce the prevalence of obesity. Shortchanging prevention efforts can lead to more costly and complicated treatment options in the future, whereas introducing small changes to young children can help them develop healthy habits for life.

The first few years of childhood may be the best time to promote healthy eating behaviors in children. Programs such as Go NAP SACC lay the foundation by helping child care providers create environments to nurture healthy eating habits and increase opportunities for physical activity for all of the children.

References

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016 Jun 7;315(21):2284-91.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, Fryar CD, Kruszon-Moran D, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016 Jun 7;315(21):2292-9.

- Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual Medical Spending Attributable To Obesity: Payer-And Service-Specific Estimates. Health Affairs. 2009;28(5).

- Gortmaker SL, Wang YC, Long MW, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Barrett JL, Kenney EL, Sonneville KR, Afzal AS, Resch SC, Cradock AL. Three interventions that reduce childhood obesity are projected to save more than they cost to implement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015 Nov;34(11):1932-9.5

- Child Care Aware. State Child Care Facts in the State of New Hampshire, 2016. Accessed 8/17/17 at: http://childcareaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/New-Hampshire.pdf; Personal communication from NH Division of Public Health Services.

- Ward DS, Benjamin SE, Ammerman AS, Ball SC, Neelon BH, Bangdiwala SI. Nutrition and physical activity in child care: results from an environmental intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Oct;35(4):352-6.

- Alkon A, Crowley AA, Neelon SE, Hill S, Pan Y, Nguyen V, Rose R, Savage E, Forestieri N, Shipman L, Kotch JB. Nutrition and physical activity randomized control trial in child care centers improves knowledge, policies, and children’s body mass index. BMC Public Health. 2014 Mar 1;14:215.

- Birch, L., Savage, J. S., & Ventura, A. (2007). Influences on the Development of Children’s Eating Behaviours: From Infancy to Adolescence. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research : A Publication of Dietitians of Canada = Revue Canadienne de La Pratique et de La Recherche En Dietetique : Une Publication Des Dietetistes Du Canada, 68(1), s1–s56.

Suggested Citation:Kenney EL, Giles CM, Flax CN, Gortmaker SL, Cradock AL, Ward ZJ, Foster S, Hammond W. New Hampshire: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) Intervention {Issue Brief}. New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Concord, NH, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; October 2017. |

The design for this brief and its graphics were developed by Molly Garrone, MA and partners at Burness.

This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only. Funded by The JPB Foundation. Results are those of the authors and not the funders. For more information, please visit: https://www.dhhs.nh.gov

Brief: NAP SACC in Early Achievers in Washington State

The information in this brief is intended for educational use only.

This brief provides a summary of the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership simulation model of integrating the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) into Washington’s Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS), Early Achievers, which awards quality ratings to early care and education (ECE) programs meeting defined standards.

The Issue

Over the past three decades, more and more people have developed obesity.1 Today, nearly nine percent of 2-5 year olds have obesity.2 Health care costs for treating obesity-related health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes were $147 billion in 2008.3 Emerging prevention strategies directed at children show great promise for addressing this issue.4 A large body of evidence shows that healthy eating, physical activity, and limited screen media time (like watching TV or smartphones) helps kids grow up at a healthy weight.

In Washington, over a quarter of 2-5 year olds attend a licensed ECE program.5 Because QRIS systems like Early Achievers incentivize ECE programs to meet high standards and provide training, they are an ideal way to help ECE programs engage in improving nutrition, physical activity, and screen time practices. The Department of Early Learning invested $91 million in Early Achievers in 2016-17.5

About NAP SACC and QRIS

NAP SACC, based on the best available scientific evidence, helps ECE providers improve nutrition, active play, and screen time practices.6,7 QRIS programs encourage providers to improve in quality by using a voluntary and rewarding (rather than regulatory and punitive) approach and offers a mechanism for implementing a time-intensive program like NAP SACC. ECE directors complete self-assessments of existing practices and receive training and technical assistance to implement changes that create healthier environments. In Washington’s hypothetical model, completing NAP SACC would be an option for ECE providers seeking to achieve Early Achievers Level 3 status. State-contracted coaches would train providers and conduct technical assistance for meeting NAP SACC goals.

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes of integrating NAP SACC into Early Achievers over 10 years (2015-2025) with costs and outcomes associated with not implementing the program. The approach assumes that 72% licensed ECE centers participate in Early Achievers, and 25% of both center-based and home-based providers adopt NAP SACC.

| Implementing NAP SACC in child care programs throughout Washington is an investment in the future. By the end of 2025:  |

Conclusions and Implications

Every child deserves a healthy start in life. This includes ensuring that all kids in child care have opportunities to eat healthy foods and be physically active, no matter where they live or where they go for child care. A state-level initiative to bring the NAP SACC self-assessment and improvement process to Washington child care programs through the Early Achievers system could prevent over a thousand cases of childhood obesity in 2025 and ensure healthy child care environments for over 160,000 children. For every $1 spent implementing this strategy with child care centers, we would save $0.08 in health care costs as a result of decreased obesity prevalence. For every $1 spent implementing this strategy with family home providers, we would save $0.02 in health care costs as a result of decreased obesity prevalence

These results reinforce the importance of investing in prevention efforts, to reduce the prevalence of obesity. Shortchanging prevention efforts can lead to more costly and complicated treatment options in the future. Introducing small changes to young children can help them develop healthy habits for life.

Evidence is growing about how to help children achieve a healthy weight. Programs such as NAP SACC are laying the foundation for healthier generations by helping ECE providers create environments that nurture healthy habits. Leaders at the federal, state, and local level should use the best available evidence to help children eat healthier diets and be more active.

References

- Flegal, K.M., Kruszon-Moran, D., Carroll, M.D., Fryar, C.D., Ogden, C.L. (2016). Trends in Obesity Among Adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA, 315(21), 2284-91.

- Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Lawman, H. G., Fryar, C. D., Kruszon-Moran, D., Kit, B. K., & Flegal, K. M. (2016). Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013–2014. JAMA, 315(21), 2292-2299.

- Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual Medical Spending Attributable To Obesity: Payer-And Service-Specific Estimates. Health Affairs. 2009;28(5).

- Gortmaker, S. L., Wang, Y. C., Long, M. W., Giles, C. M., Ward, Z. J., Barrett, J. L., …Cradock, A. L. (2015). Three interventions that reduce childhood obesity are projected to save more than they cost to implement. Health Affairs, 34(11), 1932–1939.

- DEL Early Achievers Data Dashboard and Market Rate Report, June 2015; Early Start Act Report.

- Ward, D.S., Benjamin S.E., Ammerman, A.S., Ball, S.C., Neelon, B.H., Bangdiwala, S.I. (2008). Nutrition and physical activity in child care: results from an environmental intervention. Am J Prev Med, 35(4):352-6.

- Alkon, A., Crowley, A.A., Neelon, S.E., Hill, S., Pan, Y., Nguyen, V., Rose, R., Savage, E., Forestieri, N., Shipman, L., Kotch, J.B. (2014). Nutrition and physical activity randomized control trial in child care centers improves knowledge, policies, and children’s body mass index. BMC Public Health, 14:215.

Suggested Citation:Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL, Pipito A, Kenney EL, Giles CM. Washington: NAP SACC: Researching an Intervention to Create the Healthiest Next Generation [Issue Brief]. Washington State Department of Health, Olympia, WA, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; August 2017. |

The design for this brief and its graphics were developed by Molly Garrone, MA and partners at Burness.

This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the Washington State Department of Health through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only. Funded by The JPB Foundation. Results are those of the authors and not the funders. For more information, please visit: http://www.doh.wa.gov/CommunityandEnvironment/HealthiestNextGeneration/CHOICES

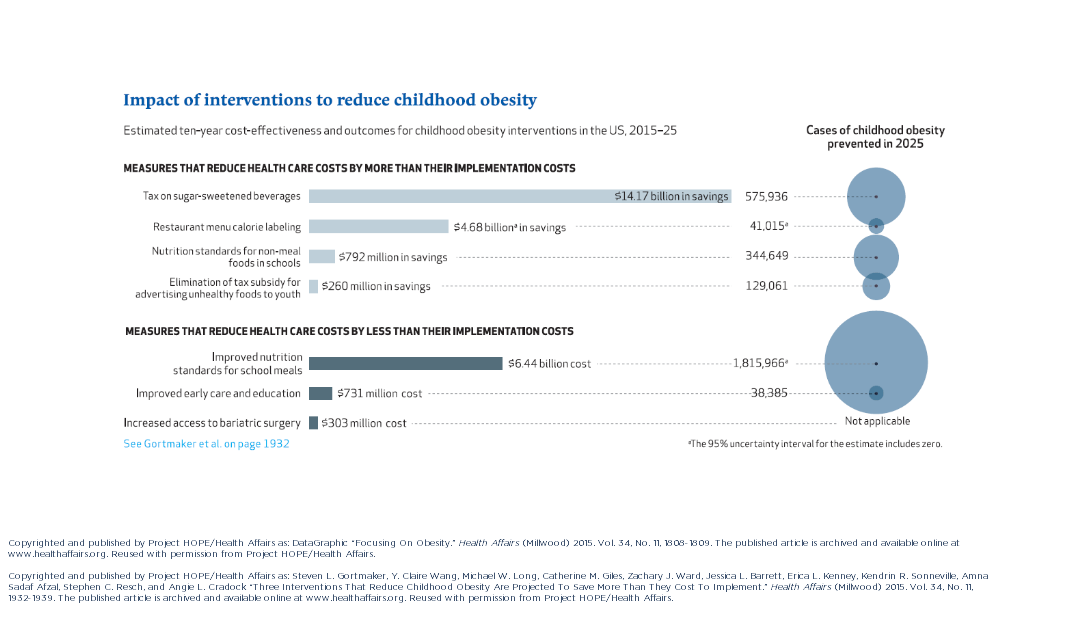

Three Interventions That Reduce Childhood Obesity Are Projected to Save More Than They Cost to Implement

A CHOICES paper identifying cost-effective nutrition interventions with broad population reach highlights the importance of primary prevention for policy makers aiming to reduce childhood obesity.

Gortmaker SL, Claire Wang Y, Long MW, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Barrett JL, Kenney EL, Sonneville KR, Afzal AS, Resch SC, Cradock AL. Three Interventions That Reduce Childhood Obesity Are Projected to Save More Than They Cost to Implement. Health Aff, 34, no. 11 (2015):1304-1311.

Reused with permission from Project HOPE/Health Affairs. The published article is archived and available online at www.healthaffairs.org.

The United States will not be able to treat its way out of the obesity epidemic with current clinical practice. Instead, reversing the tide of obesity will require expanded investment in primary prevention, focusing on a combination of interventions with broad population reach, proven individual effectiveness, and low cost of implementation.

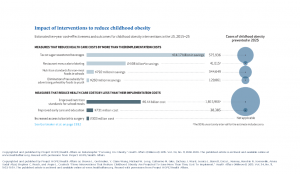

This study is the first of its kind to estimate the cost effectiveness of a wide variety of nutrition interventions high on the obesity policy agenda—documenting their potential reach, comparative effectiveness, implementation cost, and cost-effectiveness. Researchers identified three interventions that would more than pay for themselves by reducing healthcare costs related to obesity: an excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages; elimination of the tax subsidy for advertising unhealthy food to children; and nutrition standards for food and drinks sold in schools outside of school meals. Implemented nationally, these interventions would prevent 576,000, 129,100, and 345,000 cases of childhood obesity, respectively, in 2025. The projected net savings to society in obesity-related health care costs for each dollar spent would be $30.78, $32.53, and $4.56, respectively.

Additional interventions modeled include restaurant menu calorie labeling, increased access to adolescent bariatric surgery, improved early care and education, and nutrition standards for school meals. The study points out that the improvements in nutrition standards for both school meals and foods and beverages sold outside of meals through current Smart Snacks in School regulation make the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 one of the most important national obesity prevention policy achievements in recent decades.

Though researchers analyzed interventions separately, no strategy on its own would be sufficient to reverse the obesity epidemic. The study also emphasizes the importance of obesity prevention that spans across multiple settings throughout the life course. While childhood interventions are necessary to reduce obesity during the early years of life and ensure that children enter into adulthood at a healthy weight, it is critical that environments spanning the life course continue to support healthy eating and drinking behaviors.

“Policy makers looking to reverse the childhood obesity epidemic and reduce long-term obesity prevalence need to focus on implementing cost-effective preventive interventions that reach a large percentage of our nation’s children,” says lead investigator of the CHOICES Project, Dr. Steve Gortmaker, who also serves as a Professor of the Practice of Health Sociology and the Director of the Prevention Research Center on Nutrition and Physical Activity at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The study notes that interventions affecting both children and adults are particularly attractive, since near-term health care cost savings can be achieved by reducing adult obesity, while laying the ground work for long-term cost savings by reducing childhood obesity. The sugar-sweetened beverage excise tax, for example, would save $14.2 billion in net costs over the course of the decade, primarily due to reductions in adult health care costs.

Interventions that can achieve near-term health cost savings among adults and reduce childhood obesity offer policy makers an opportunity to make long-term investments in children’s health while generating short-term returns.