The information in this resource is intended only to provide educational information. This profile describes the estimated benefits, activities, resources, and leadership needed to implement a strategy to improve child health. This information can be useful for planning and prioritization purposes.

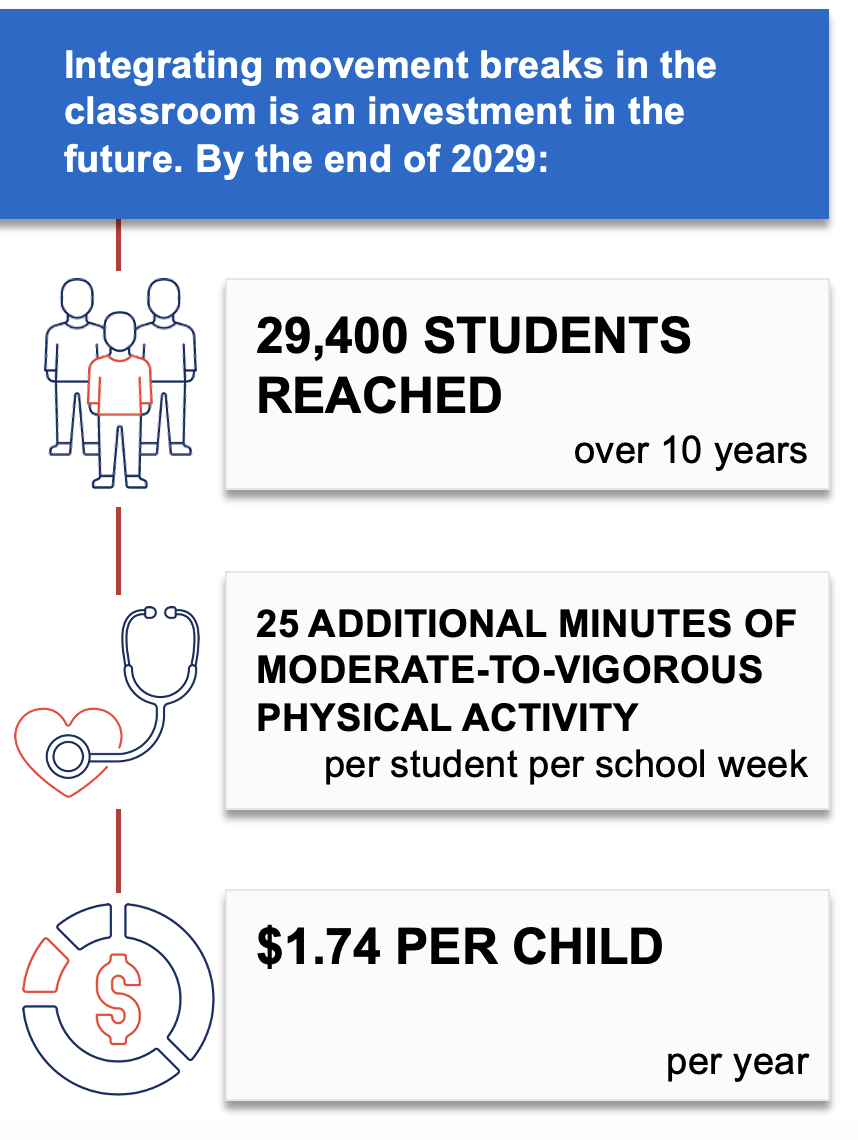

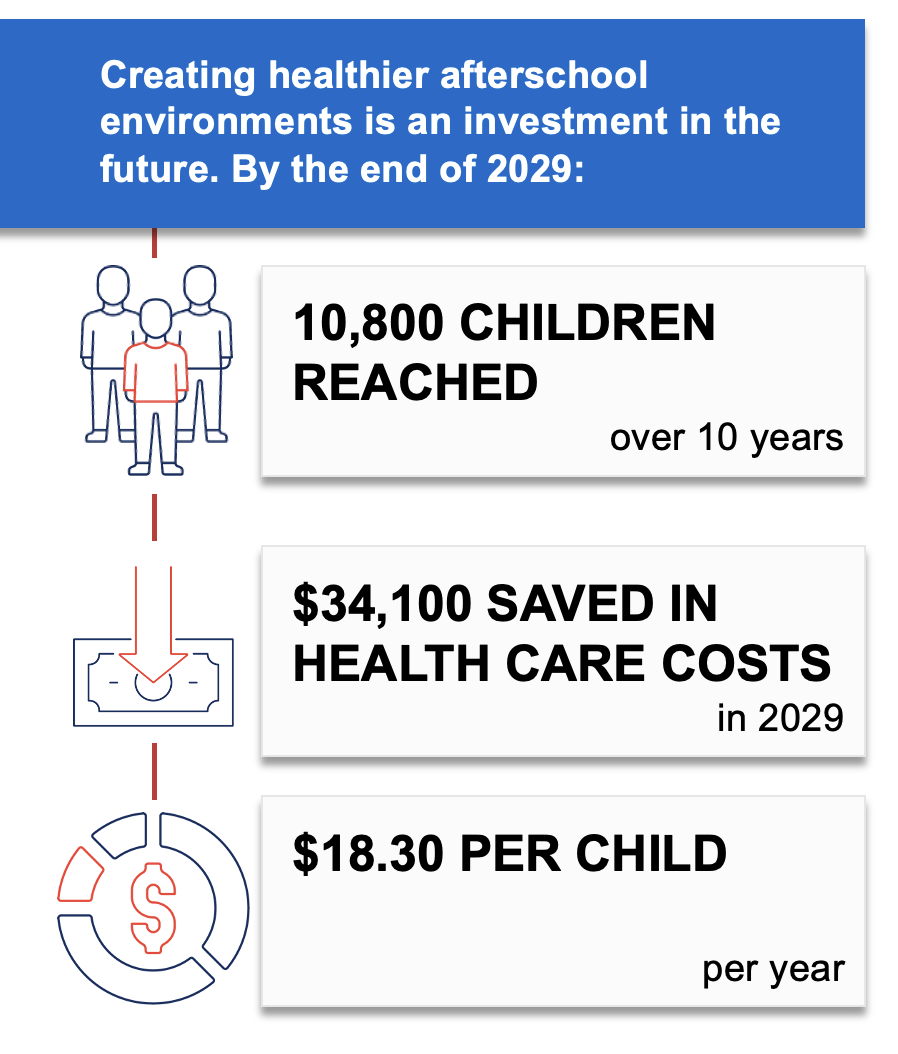

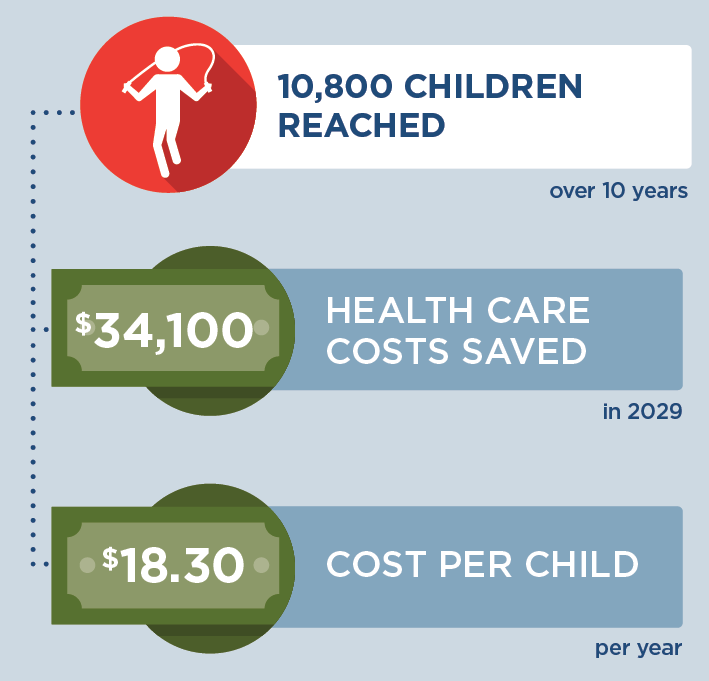

- Policy requiring schools to provide opportunities for students to participate in physical activity during the school day for at least 30 minutes a day or 150 minutes a week.

What population benefits?

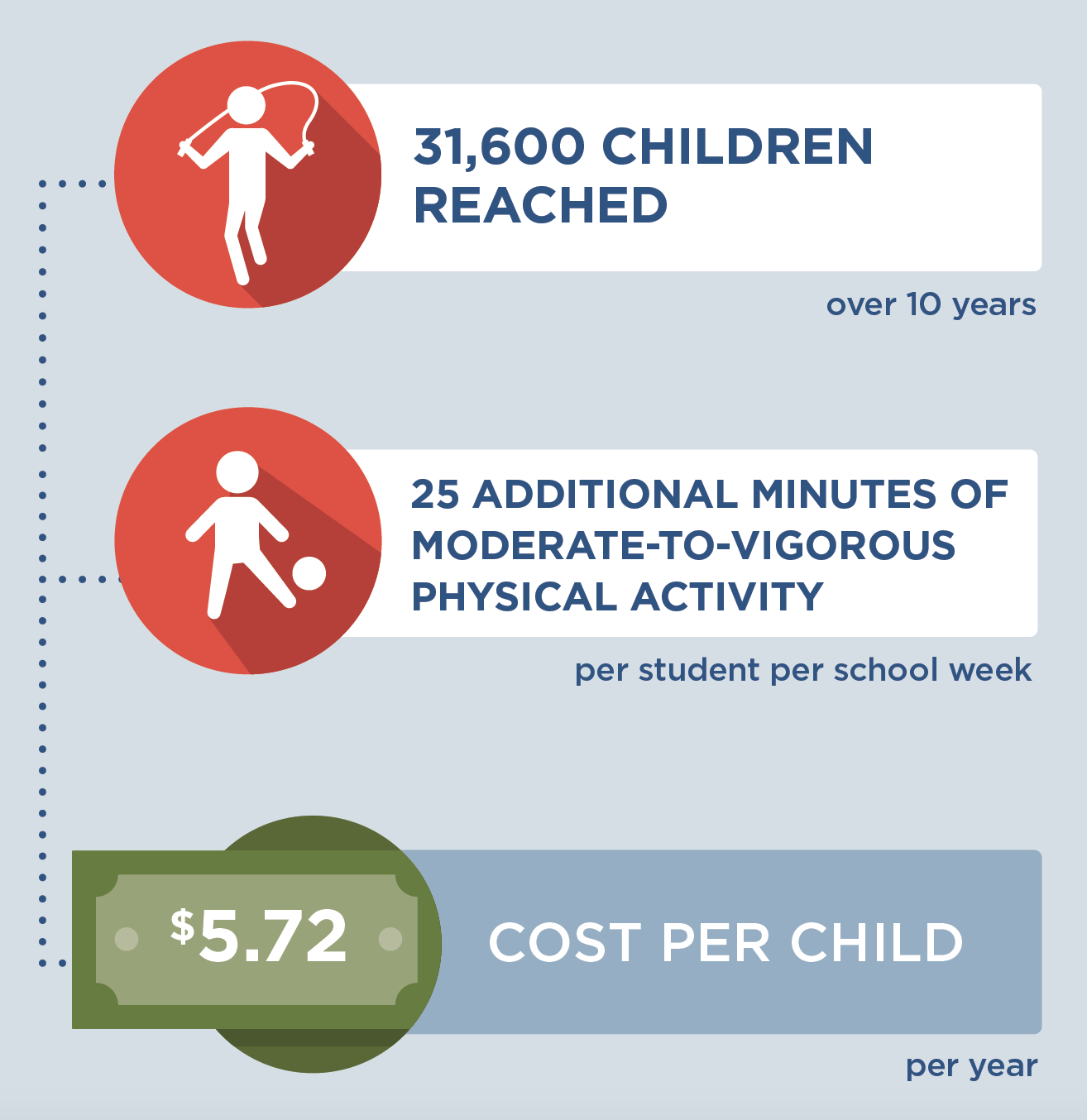

Children in grades K-8 (ages 5-14).

What are the estimated benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

Increase students’ moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels and, in turn, promote healthy weight.

What activities and resources are needed?

| Activities | Resources | Who Leads? |

| Coordinate and support implementation of the active school day policy | • Time for school health and wellness staff (Director, Assistant Director, Physical Education Director, Coordinators, and business office staff) to provide support | School district |

| Train Wellness Champions, physical education teachers, and lunch monitors in physical activity promotion | • Time for training consultant to train physical education teachers, Wellness Champions, and lunch monitors • Time for Wellness Champions to attend trainings on policy and implementation strategies (either recess or movement breaks in the classroom) • Time for physical education teachers to attend training on quality PE strategies • Time for lunch monitors to attend trainings on recess strategies (in schools implementing recess strategies) • Travel costs for lunch monitors to attend trainings • Cost of space rental, food, and promotional flyers for trainings |

School district |

| Develop and maintain materials to support implementation | • Cost to develop an online portal or printed materials to support implementation • Cost to maintain the online portal or replace printed materials in subsequent years |

School |

| Implement strategies that promote physical activity in schools | • Time for Wellness Champions and instructional coaches to lead implementation of strategies promoting physical activity • Time for Wellness Champions and school principals to review performance on strategy implementation |

School district |

| Purchase equipment and materials for a more active school day | • Cost of equipment and curricula for promoting physical activity in physical education and in recess or the classroom | School district |

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Cradock AL, Barrett JL, Kenney EL, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Long MW, Resch SC, Pipito AA, Wei ER, Gortmaker SL. Using cost-effectiveness analysis to prioritize policy and programmatic approaches to physical activity promotion and obesity prevention in childhood. Prev Med. 2017 Feb;95 Suppl: S17-S27. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.017. Supplemental Appendix with strategy details available at: https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1- s2.0-S0091743516303395-mmc1.docx

- Browse more CHOICES research briefs & reports in the CHOICES Resource Library.

- Explore and compare this strategy with other strategies on the CHOICES National Action Kit.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES Strategy Profile: Active School Day. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; December 2023.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose. The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Adapted from the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist