In this coffee chat, guest speakers from the Lowell Community Health Center shared how they have engaged partners in developing community-tailored strategies that can promote nutrition and physical activity and reduce disparities through their REACH LoWELL initiative.

Topic: Active Living

Coffee Chat: Roundtable Discussions: Advancing Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Health Equity

In this coffee chat, we shared an overview of our community and hosted roundtable discussions for participants to share and connect with others about their work to advance nutrition, physical activity, and health equity.

Fact Sheet: Movement Breaks in the Classroom (Grades K-5)

The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose.

Not all students have access to safe streets, playgrounds, or spaces to be physically active. Movement breaks in the classroom provide students with the opportunity to be physically active and help them meet the national physical activity standards1 of at least 60 minutes per day.

- Movement breaks are short physical activity opportunities done in the classroom.

- Only one in four children2 meets the national recommendations1 of physical activity. Movement breaks can supplement other school physical activity opportunities, like recess and physical education, to help more children meet physical activity guidelines.3,4

- Students enjoy having opportunities to be physically active in the classroom, and movement breaks allow students to refocus and bring full attention back to academic work.5-7

Movement breaks can help teachers create a positive classroom climate and culture.8

- Movement breaks in the classroom can increase students’ time spent on tasks3,4 and engagement in learning.4

- Movement breaks can help with classroom management when implemented appropriately.4,5

- Students say they can focus and learn better and are more excited about school after movement breaks.6,7

- Teachers enjoy leading movement breaks. When teachers participate in the breaks, they can also experience the health benefits of being physically active.4

Childhood is a crucial period for developing movement skills and healthy habits. Providing students with physical activity will help them build a foundation for overall health and well-being.

- Regular physical activity can reduce anxiety, stress, and symptoms of depression and improve self-esteem.1

- Active students generally have better heart and lung health, stronger muscles and bones, and healthier body weight than inactive students.1

- Students who are physically active tend to have better grades, attendance at school, memory, and attention.9

Experts agree that students should have opportunities for classroom physical activity. Teachers can help students meet the physical activity recommendations by incorporating movement breaks in the classroom.10-12

- Providing resources and proper training in effective ways to promote movement in the classroom can increase teacher uptake and confidence in implementation and provide children with opportunities for physical activity.4

- Some tips to help teachers run movement breaks are:

✓Introduce and demonstrate activity breaks using a video or other examples.7 Tailor the breaks to the context of your classroom.4

✓Be consistent with the days and times you do movement breaks.7

✓Outline expectations for students and make sure children are aware of their physical space.7 Modify activities to allow all students to participate in the breaks.4 Deep breaths after the movement break can help students transition to the next activity.5

✓Participate in the movement break activities with the students when possible.4

✓Explain the benefits of moving during the school day and provide students with positive reinforcement, especially those who may find movement breaks more challenging.7

✓Consider students’ preferences when doing breaks.3 Students like movement breaks that allow choice, imagination, and that are at an appropriate level of difficulty. They do not like breaks that are too difficult or silly.6

Additional Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. Available at: https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Classroom Physical Activity. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/classroom-pa.htm

- Carter J, Greene J, Neeraja S, Bovenzi, M, Sabir M, Carter S, Bolton AA, Barrett JL, Reiner JR, Cradock AL. Boston, MA: Movement Breaks in the Classroom {Issue Brief}. Boston Public Schools, Boston Public Health Commission, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; August 2022. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-movement-breaks

- CHOICES Strategy Profile: Movement Breaks in the Classroom. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; October 2022. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/movement-breaks-profile

- The Community Preventive Services Task Force. Physical Activity: Classroom-based Physical Activity Break Interventions. The Community Guide. 2021:8. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/physical-activity-classroom-based-physical-activity-break-interventions

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018:118. Accessed November 29, 2021. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

- Data Resource Center for Child & Adolescent Health. National Performance Measure 8.1: Percent of children, ages 6 through 11, who are physically active at least 60 minutes per day. Childhealthdata.org. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://www.childhealthdata.org/browse/survey/results?q=9184&r=1

- The Community Preventive Services Task Force. Physical Activity: Classroom-based Physical Activity Break Interventions. The Guide to Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide). Published August 9, 2021. Accessed November 29, 2021. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/physical-activity-classroom-based-physical-activity-break-interventions

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strategies for Classroom Physical Activity in Schools. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018:25. Accessed November 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/classroom-pa.htm

- Campbell AL, Lassiter JW. Teacher perceptions of facilitators and barriers to implementing classroom physical activity breaks. J Educ Res. 2020;113(2):108-119. doi:10.1080/00220671.2020.1752613

- Watson A, Timperio A, Brown H, Hesketh KD. Process evaluation of a classroom active break (ACTI-BREAK) program for improving academic-related and physical activity outcomes for students in years 3 and 4. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):633. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6982-z

- Cline A, Knox G, De Martin Silva L, Draper S. A Process Evaluation of A UK Classroom-Based Physical Activity Intervention—‘Busy Brain Breaks.’ Children. 2021;8(2):63. doi:10.3390/children8020063

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School-Based Physical Activity Improves the Social and Emotional Climate for Learning.Cdc.gov. Published March 29, 2021. Accessed March 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/school_based_pa_se_sel.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010:84. Accessed November 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/health_and_academics/pdf/pa-pe_paper.pdf

- SHAPE America. Shape of the Nation: Status of Physical Education in the USA. SHAPE America – Society of Health and Physical Educators. 2016:142. Accessed November 29, 2021. https://www.shapeamerica.org/advocacy/son/

- Institute of Medicine. Educating the Student Body: Taking Physical Activity and Physical Education to School. National Academies Press. 2013:420. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/18314/educating-the-student-body-taking-physical-activity-and-physical-education

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Classroom Physical Activity. Cdc.gov. Published July 27, 2022. Accessed Oct 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/classroom-pa.htm

Suggested Citation

Get the Facts: Movement Breaks in the Classroom (Grades K-5). Prevention Research Center on Nutrition and Physical Activity Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; March 2023.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders. The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose.

Coffee Chat: Engaging decision-makers to advance healthy eating, physical activity, and health equity priorities

In this coffee chat, Oami Amarasingham, Deputy Director of the Massachusetts Public Health Association, shares tips and insights to help participants learn how to successfully engage decision-makers to advance prevention.

Strategy Profile: Creating Healthier Afterschool Environments

The information in this resource is intended only to provide educational information. This profile describes the estimated benefits, activities, resources, and leadership needed to implement a strategy to improve child health. This information can be useful for planning and prioritization purposes.

- Creating healthier afterschool environments is a strategy to improve nutrition and physical activity policies & practices through the Out of School Nutrition and Physical Activity (OSNAP) initiative for children in grades K-5 attending state-administered 21st Century Learning afterschool programs.

What population benefits?

Children in grades K-5 attending state-administered 21st Century Learning afterschool programs.

What are the estimated benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

Increase vigorous physical activity and improve nutritional quality of snacks and beverages offered in afterschool programs, and, in turn, promote healthy child weight.

What activities and resources are needed?

| Activities | Resources | Who Leads? |

| Issue regulations to improve nutrition and physical activity policies and practices in afterschool programs | • Time to issue and communicate regulations | State government |

| Provide training and technical assistance to regional Healthy Afterschool trainers on how to lead learning collaborative sessions | • Time for state Healthy Afterschool coordinator to lead trainings • Time for regional Healthy Afterschool trainers to be trained and receive technical assistance • Travel costs • Training material costs |

State healthy afterschool coordinator |

| Conduct regional learning collaboratives with afterschool program staff including training and technical assistance on goals and implementation activities | • Time for regional Healthy Afterschool trainers to lead learning collaboratives and provide technical assistance • Time for afterschool program staff to attend learning collaboratives and receive technical assistance • Training material costs • Travel costs |

Regional healthy afterschool trainer |

| Assess and implement actions to change program practices to meet Healthy Afterschool standards | • Time for afterschool program staff to conduct program practice self-assessments and implement changes at their program • Increase in food costs to provide snacks in compliance with nutrition standards to children attending Healthy Afterschool programs |

Afterschool program director |

| Develop CEU-accredited course for local program staff | • Cost to create a CEU-accredited course | State healthy afterschool coordinator |

| Provide educational materials and incentives to local program staff | • Material and incentive costs | State government |

| Monitor compliance to ensure afterschool programs are following programmatic requirements | • Time for state monitoring and compliance staff to monitor compliance • Travel costs |

State government monitoring and compliance staff |

| Establish a Healthy Afterschool recognition and monitoring website | • Time to create and maintain website | State government website developer |

Strategy Modification

This strategy could be modified to benefit children who participate in out-of-school programs administered by other organizations (e.g., YMCA or Boys and Girls Club of America). With this modification, the activities necessary to carry out the voluntary recognition program may not be included (e.g., issuing regulations, creating a healthy afterschool nutrition website, and monitoring compliance). With this modification, the impact on health is expected to be similar, and the impact on reach and cost may vary.

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Cradock AL, Barrett JL, Kenney EL, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Long MW, Resch SC, Pipito AA, Wei ER, Gortmaker SL. Using cost-effectiveness analysis to prioritize policy and programmatic approaches to physical activity promotion and obesity prevention in childhood. Prev Med. 2017 Feb;95 Suppl: S17-S27. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.017. Supplemental Appendix with strategy details available at: https://ars.els-cdn.com/ content/image/1-s2.0-S0091743516303395-mmc1.docx

- Browse more CHOICES research briefs & reports in the CHOICES Resource Library.

- Explore and compare this strategy with other strategies on the CHOICES National Action Kit.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES Strategy Profile: Creating Healthier Afterschool Environments. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; May 2023.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose. The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Adapted from the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist

Strategy Profile: Movement Breaks in the Classroom

The information in this resource is intended only to provide educational information. This profile describes the estimated benefits, activities, resources, and leadership needed to implement a strategy to improve child health. This information can be useful for planning and prioritization purposes.

- Movement Breaks in the Classroom is a strategy to promote physical activity during the school day by incorporating five-to-10-minute movement breaks in K-5 public elementary school classrooms.

What population benefits?

Children in grades K-5 attending public elementary schools.

What are the estimated benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

Increase students’ moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels and, in turn, promote healthy child weight.

What activities and resources are needed?

| Activities | Resources | Who Leads? |

| Identify and compile materials and content for training and implementation | • Time for physical activity coordinator to identify and compile materials/content to train teachers • Time for physical activity coordinator to develop a movement break library to support teachers with implementation |

Physical activity coordinator |

| Recruit schools and coordinate training | • Time for physical activity coordinator to communicate and plan training activities with schools | Physical activity coordinator |

| Train classroom teachers in movement breaks | • Time for physical activity coordinator to provide training • Time for classroom teachers to attend trainings |

Physical activity coordinator |

| Materials and equipment provided to teachers to implement movement breaks | • Material costs | School districts or local government |

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

The Community Preventive Services Task Force. Physical Activity: Classroom-based Physical Activity Break Interventions. The Community Guide. 2021:8. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/physical-activity-classroom-based-physical-activity-break-interventions

Selected CHOICES research brief including cost-effectiveness metrics:

Carter J, Greene J, Neeraja S, Bovenzi, M, Sabir M, Carter S, Bolton AA, Barrett JL, Reiner JR, Cradock AL. Boston, MA: Movement Breaks in the Classroom {Issue Brief}. Boston Public Schools, Boston Public Health Commission, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; August 2022. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-movement-breaks-boston

Good N, Bolton AA, Barrett JL, Reiner JF, Cradock AL. Massachusetts: Movement Breaks in the Classroom {Issue Brief}. The CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; June 2023. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-movement-breaks-ma

- Browse more CHOICES research briefs & reports in the CHOICES Resource Library.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES Strategy Profile: Movement Breaks in the Classroom. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; October 2022.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose. The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Adapted from the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist

Brief: Movement Breaks in the Classroom in Boston, MA

The information in this brief is intended only to provide educational information.

A version of this brief was published in May 2022. This brief was updated in August 2022 to reflect revised projections for Boston’s population.

This brief summarizes a CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership model examining a strategy to integrate movement breaks into school classrooms in Boston, MA. This strategy incorporates five-to-10-minute classroom physical activity breaks during class time in kindergarten to fifth grade classrooms.

The Issue

One in three first-graders in Boston has overweight or obesity.1 Being physically active can support children in growing up at a healthy weight, though not all schools provide students with the recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week or 30 minutes per day.2,3 Regular physical activity can boost brain health, including improved cognition and reduced symptoms of depression.4 Students who are physically active also tend to have better grades, attendance at school, and stronger muscles and bones.4

Experts suggest that schools provide opportunities for classroom physical activity,5 but few schools offer it.6 Movement breaks supplement other critical school physical activity opportunities, like recess and physical education, and help children meet recommendations for physical activity.5 Providing all students with opportunities to be physically active will ensure more students are growing up at a healthy weight and ready to learn.

About the Movement Breaks in the Classroom Strategy

We can provide healthier opportunities for all children by initiating strategies with strong evidence for effectiveness. To implement the Movement Breaks strategy, teachers, Wellness Champions, and staff would receive training, equipment, and materials to incorporate short activity breaks in the classroom to help children move more.7,8 Initiating strategies with strong evidence for effectiveness like Movement Breaks in the Classroom helps fulfill Boston Public School’s (BPS) Physical Education and Physical Activity Policy requirements for schools to offer physical activity opportunities during the school day.3 This strategy also aligns with BPS’ Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child approach, which supports students’ holistic health by promoting positive classroom environments that foster physical activity and learning.

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

A CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes over a 10-year time horizon (2020-2030) of implementing movement breaks with the costs and outcomes associated with not implementing them. We assumed that elementary schools in Boston Public Schools serving grades K-5 would receive training, equipment, and materials to implement movement breaks. The model assumes that 56% of those trained would implement the movement breaks in classrooms.

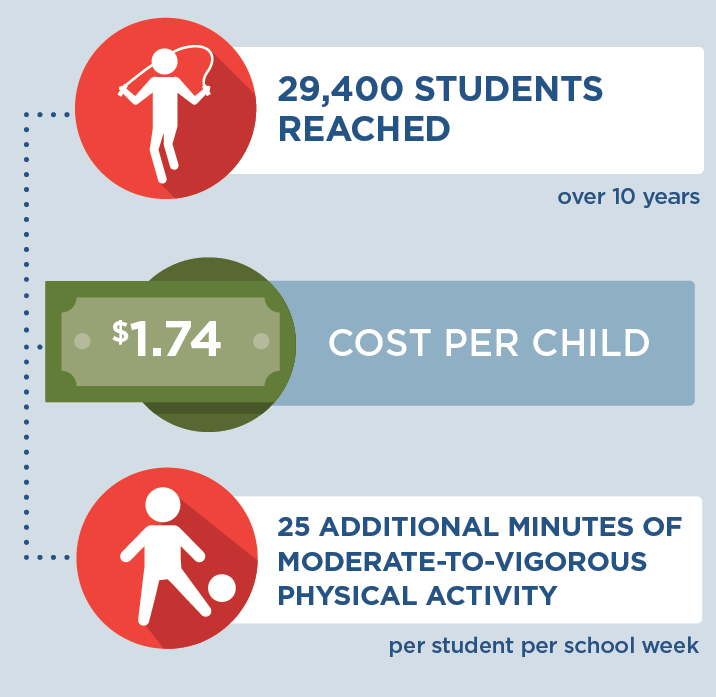

Implementing movement breaks in the classroom is an investment in the future. By the end of 2030: |

Conclusions and Implications

If movement breaks were incorporated into classrooms, we project that over 10 years, 29,400 students would benefit. The students would increase their moderate-to-vigorous-physical activity levels by 25 minutes per school week, helping them meet wellness goals of 150 minutes of physical activity per week.3 This strategy would also prevent 37 cases of childhood obesity (in 2030) and save $35,300 in health care costs related to excess weight over 10 years. The average annual cost to implement this program in every public elementary school (Grades K-5) in Boston would be $1.74 per student, or just over $1,000 per school per year.

In addition to promoting a healthy weight, classroom physical activity benefits students in other important ways. By training and equipping over 600 teachers and other school staff yearly to incorporate movement breaks in the classroom, this strategy could help all Boston Public Schools cultivate a positive school climate and improve social emotional learning.9 Participation in movement breaks are associated with students spending more time on task,5 and teachers report that students are more engaged, supportive of each other, and responsive to teacher instructions after participating in a movement break.10

Childhood is a crucial period for developing healthy habits. Many preventive strategies can play a critical role in helping children establish healthy behaviors early on in life. Providing movement breaks in the classroom is an easy and relatively low-cost way to increase physical activity and support the overall health and wellness of all Boston students.

References

-

School Health Services, Department of Public Health. Results from the Body Mass Index Screening in Massachusetts Public School Districts, 2017. 2020:88. https://www.mass.gov/doc/the-status-of-childhood-weight-in-massachusetts-2017

-

Boston Public Schools, Health and Wellness Department. School Health Profiles [2018]: Boston, MA.

-

Boston Public Schools. Physical Education & Physical Activity Policy. 2020:8. Superintendent’s Circular. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rSGwpFaa4LsPKxjhdsHxz2IaXg3ZFVtE/view?usp=embed_facebook

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020-04-21T09:02:35Z 2010.

-

The Community Preventive Services Task Force. Physical Activity: Classroom-based Physical Activity Break Interventions. The Community Guide. 2021:8.

-

Classroom Physical Activity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed Oct 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/classroom-pa.htm

-

Erwin HE, Beighle A, Morgan CF, Noland M. Effect of a low-cost, teacher-directed classroom intervention on elementary students’ physical activity. J Sch Health. 2011;81(8):455-461.

-

Murtagh E, Mulvihill M, Markey O. Bizzy Break! The effect of a classroom-based activity break on in-school physical activity levels of primary school children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2013;25(2):300-307.

-

School-Based Physical Activity Improves the Social and Emotional Climate for Learning. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,. Accessed March 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/school_based_pa_se_sel.htm

-

Campbell AL, Lassiter JW. Teacher perceptions of facilitators and barriers to implementing classroom physical activity breaks. J Educ Res. 2020;113(2):108-119

Suggested Citation:Carter J, Greene J, Neeraja S, Bovenzi M, Sabir M, Carter S, Bolton AA, Barrett JL, Reiner JR, Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL. Boston, MA: Movement Breaks in the Classroom {Issue Brief}. Boston Public Schools, Boston Public Health Commission, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; August 2022. For more information, please visit www.choicesproject.org |

A version of this brief was published in May 2022. This brief was updated in August 2022 to reflect revised projections for Boston’s population.

The design for this brief and its graphics were developed by Molly Garrone, MA and partners at Burness.

This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the Boston Public Health Commission through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only. This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Fact Sheet: Physical Activity is Key for Young Kids’ Health (Ages 3 through 5)

The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose.

Early childhood is a critical time to establish movement skills and learn healthy habits. Regular physical activity is vital for healthy growth and development.

- Being active improves bone health,1–3 helps maintain a healthy weight,2,3 and strengthens important muscles in the bodies of young children.

Young kids should get at least three hours each day of total physical activity to enhance their growth and development.3,5

- Many (but not all) young children get recommended levels of physical activity.4,5

- Participating in a variety of activities like playing dress up, or more moderate intensity activities like riding tricycles, and more vigorous intensity activities like skipping and jumping helps young children grow up healthy

- However, only about one-third of kids’ physical activity during child care hours is done at moderate-to-vigorous intensity levels.6

Increasing physical activity in early care and education settings is a national health priority.7

- Only about one-third of physical activity that happens during a child’s time in an early care and education setting is done at moderate-to-vigorous intensity levels.6 Most opportunities should allow for moderate-to-vigorous intensity movements, like running.8

- Every day, early educators can offer multiple active play opportunities, like playing on a playground, in addition to structured activities, like playing tag.

- ✓Planning safe, fun outdoor activities that can occur in imperfect weather7,8,9and integrating physical activity into educational lessons can help children move more.4,10

- Young kids are generally physically active in short bursts,8,11 so offering a variety of activities and opportunities throughout the day can help young kids accumulate enough movement.

- While in early care and education settings, all young children should have about 15 minutes per hour of active and outdoor play opportunities (or about two hours per eight-hour day in care).4,8

Early care and education settings are important places for helping the children who spend time there to move more.11

- Having open spaces and accessible portable play equipment, like balls or soft building blocks, can promote physical activity for all children,4,12–14 even in smaller early care spaces.

- Children should have daily opportunities to play outside.4,8,13

- Early care educators can support physical activity through:

- ✓Modifying games and activities to help all children stay moving throughout the duration of the activity, including children with disabilities or lower fitness levels.15,16

- ✓Participating in physical activity with the children.* This motivates children to move,10,17 especially those who are less active.17

- ✓Sharing ideas for games to play or suggesting ways to go back into games to help children stay moving.17

- ✓Not taking physical activity opportunities away from children as a punishment.4,8

*Added benefit!: Initiating and engaging in physical activity with children can help educators be more physically active too. Being physically active reduces the risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and depression and also leads to better sleep and less anxiety.3

Additional Resources

The following additional resources may be useful to:

✓Help children move more

- Stolley M. Hip Hop to Health Jr. SNAP-Ed Toolkit. Available at https://snapedtoolkit.org/interventions/programs/hip-hop-to-health-jr

- Go NAP SACC (Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care). Available at https://gonapsacc.org

✓Provide more guidance on physical activity and young children

- Early Care and Education. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/strategies/childcareece.html

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2018. Available at https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

- Health Benefits of Physical Activity for Children. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adults/health-benefits-of-physical-activity-for-children.html

References

- Carson V, Lee EY, Hewitt L, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between physical activity and health indicators in the early years (0-4 years). BMC Public Health. 2017;17(5):854. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4860-0

- Pate RR, Hillman CH, Janz KF, et al. Physical Activity and Health in Children Younger than 6 Years: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1282-1291. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001940

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018:118. Accessed November 29, 2021. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

- Institute of Medicine. Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies. (Birch LL, Parker L, Burns A, eds.). The National Academies Press; 2011. doi:10.17226/13124

- Bruijns BA, Truelove S, Johnson AM, Gilliland J, Tucker P. Infants’ and toddlers’ physical activity and sedentary time as measured by accelerometry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):14. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-0912-4

- Tassitano RM, Weaver RG, Tenório MCM, Brazendale K, Beets MW. Physical activity and sedentary time of youth in structured settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):160. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-01054-y

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Increase the proportion of child care centers where children aged 3 to 5 years do at least 60 minutes of physical activity a day — PA-R01. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/physical-activity/increase-proportion-child-care-centers-where-children-aged-3-5-years-do-least-60-minutes-physical-activity-day-pa-r01

- American Academy of Pediatrics, National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care (U.S.), American Public Health Association, United States, eds. Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards, Guidelines for Early Care, and Education Programs. Fourth edition. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2019.

- Timmons BW, Leblanc AG, Carson V, et al. Systematic review of physical activity and health in the early years (aged 0-4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab Physiol Appl Nutr Metab. 2012;37(4):773-792. doi:10.1139/h2012-070

- Physical Activity Alliance. Physical Activity for Preschoolers during the COVID Pandemic. Published online April 2021. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://paamovewithus.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/PAA-Preschool-Covid-FINAL-04-13-2021.pdf

- Ruiz RM, Tracy D, Sommer EC, Barkin SL. A novel approach to characterize physical activity patterns in preschool-aged children. Obesity. 2013;21(11):2197-2203. doi:10.1002/oby.20560

- Hoyos-Quintero AM, García-Perdomo HA. Factors Related to Physical Activity in Early Childhood: A Systematic Review. J Phys Act Health. 2019;16(10):925-936. doi:10.1123/jpah.2018-0715

- Tonge KL, Jones RA, Okely AD. Correlates of children’s objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in early childhood education and care services: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2016;89:129-139. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.019

- Terrón-Pérez M, Molina-García J, Martínez-Bello VE, Queralt A. Relationship Between the Physical Environment and Physical Activity Levels in Preschool Children: A Systematic Review. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2021;8(2):177-195. doi:10.1007/s40572-021-00318-4

- Physical Activity for Students With Special Needs. Action for Healthy Kids. Published September 6, 2018. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.actionforhealthykids.org/physical-activity-for-students-with-special-needs/

- Including All Children: Health for Kids With Disabilities. Action for Healthy Kids. Published September 4, 2018. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.actionforhealthykids.org/including-all-children-health-for-kids-with-disabilities/

- Kippe KO, Fossdal TS, Lagestad PA. An Exploration of Child–Staff Interactions That Promote Physical Activity in Pre-School. Front Public Health. 2021;9:998. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.607012

Suggested Citation

Get the Facts: Physical Activity is Key for Young Kids’ Health (Ages 3 through 5). Prevention Research Center on Nutrition and Physical Activity Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; May 2022.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders. The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose.

Strategy Profile: Safe Routes to School

The information in this resource is intended only to provide educational information. This profile describes the estimated benefits, activities, resources, and leadership needed to implement a strategy to improve child health. This information can be useful for planning and prioritization purposes.

- Safe Routes to School is a program that supports the use of physically active modes of transportation to and from school, and aims to help children in grades K-8 safely walk and bicycle to school through infrastructure improvements, education, enforcement, and promotional activities.

What population benefits?

Children in grades K-8 who switch from passive to active travel to school after their school adopts an active transport program.

What are the estimated benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

Increase physical activity and, in turn, promote healthy child weight.

What are the additional benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

The costs of implementing this strategy could be offset by savings from…

↓ Decrease in driving, parking, and vehicle ownership and operation costs

↓ Decrease in travel time for families using their own vehicles for transportation

↓ Decrease in pedestrian and bicycle injuries and vehicle crash costs

↓ Decrease in air, greenhouse gas, water, and noise pollution costs

What activities and resources are needed?

| Activities | Resources | Who Leads? |

| Oversee implementation of Safe Routes to School program | • Time for Safe Routes to School coordinator(s) to oversee and manage implementation of the program • Time for Safe Routes to School committee to select and provide guidance on projects, including advise and award grants, provide technical assistance to programs, communicate between Safe Routes to School programs and partners, and advocate for programs |

Safe Routes to School coordinator(s) and committee members |

| Attend Safe Routes to School committee meetings | • Time for Safe Routes to School committee members to attend meetings • Travel costs for Safe Routes to School committee members |

Safe Routes to School committee members |

| Improve infrastructure around schools | • Infrastructure project costs | Local government or other organization and schools |

| Adopt key components of Safe Routes to School Framework (e.g., education, encouragement, equity, enforcement, and evaluation) | • Non-infrastructure project costs | Local government or other organization and schools |

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Selected CHOICES research brief including cost-effectiveness metrics:

McCulloch SM, Barrett JL, Reiner JF, Cradock AL. Wisconsin: Safe Routes to School {Issue Brief}. Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Division of Public Health, Madison, WI, & East Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, Menasha, WI and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; May 2021. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-safe-routes-to-school-wisconsin/

Reiner J, Barrett J, Giles C, Cradock AL. Houston: Safe Routes to School {Issue Brief}. Houston Health Department, Houston, TX and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; December 2019. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-srts-houston-tx

Pelletier J, Reiner J, Barrett J, Cradock AL, Giles C. Minnesota: Safe Routes to School (SRTS) {Issue Brief}. Minnesota Department of Health (MDH), St. Paul, MN, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; March 2019. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-saferoutes-to-school-minnesota

- Browse more CHOICES research briefs & reports in the CHOICES Resource Library.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES Strategy Profile: Safe Routes to School. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; April 2022.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose. The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Adapted from the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist

Strategy Profile: Active Physical Education (Active PE)

The information in this resource is intended only to provide educational information. This profile describes the estimated benefits, activities, resources, and leadership needed to implement a strategy to improve child health. This information can be useful for planning and prioritization purposes.

- Active PE is a policy that requires that 50% of time provided in physical education classes for grades K-8 be spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Physical education teachers are trained to promote physical activity during PE classes using the SPARK or CATCH curricula.

What population benefits?

Children in grades K-8 (5-14 years old).

What are the estimated benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

Increase students’ moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels and, in turn, promote healthy child weight.

What activities and resources are needed?

| Activities | Resources | Who Leads? |

| Oversee training and implementation of Active PE in schools | • Time for state PE coordinator to oversee implementation and training | State PE coordinator |

| Monitor compliance with moderate-to-vigorous physical activity policy | • Time for state PE coordinator to monitor compliance with policy | State PE coordinator |

| Train PE teachers through state trainings | • Time for SPARK/CATCH training consultant to lead trainings • Time for PE teachers to attend trainings • Travel costs for PE teachers and SPARK/CATCH training consultants to attend trainings |

SPARK/CATCH training consultant |

| Purchase PE equipment and curricula | • PE equipment costs • SPARK or CATCH curricula costs |

Schools |

| Train principals in assessing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in PE classes at a state principals association event | • Time for training consultant to lead trainings • Incremental time increase for principals to attend trainings on evaluating PE • Travel costs for training consultants |

Training consultant |

Strategy Modification

State and local health agencies modified this strategy in the following ways. 1) Some health agencies modified this strategy to be a best practice or implementation guideline instead of a policy. With this modification, the strategy would cost less because activities to monitor compliance, including training principals, would not occur. Additionally, a percentage – instead of all PE teachers – might be trained using this modification, which would mean reaching fewer children. 2) Some health agencies modified this strategy to use a train-the-trainer model. This modifies the training model so that the training consultants train school district master trainers and the master trainers lead trainings for the PE teachers. Modifying the strategy this way could cost less.

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Cradock AL, Barrett JL, Kenney EL, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Long MW, Resch SC, Pipito AA, Wei ER, Gortmaker SL. Using cost-effectiveness analysis to prioritize policy and programmatic approaches to physical activity promotion and obesity prevention in childhood. Prev Med. 2017 Feb;95 Suppl: S17-S27. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.017. Supplemental Appendix with strategy details available at: https://ars.els-cdn.com/ content/image/1-s2.0-S0091743516303395-mmc1.docx

Selected CHOICES research brief including cost-effectiveness metrics:

Hopkins H, Lange J, Olson E, Taylor-Watts S, Jenkins L, McCulloch S, Barrett J, Reiner J, and Cradock AL. Iowa: Active Physical Education (PE) {Issue Brief}. Iowa Department of Public Health, Iowa Department of Education, Des Moines, IA, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; April 2021. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-active-pe-iowa

- Access the SPARK PE curriculum at https://sparkpe.org

- Access the CATCH PE curriculum at https://catchinfo.org/modules/physical-education

- Browse more CHOICES research briefs & reports in the CHOICES Resource Library.

- Explore and compare this strategy with other strategies on the CHOICES National Action Kit.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES Strategy Profile: Active Physical Education (Active PE). CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; April 2022.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose. The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Adapted from the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist