A CHOICES study finds that strategies to reduce television exposure could help reduce childhood obesity at a relatively low cost.

Kenney EL, Mozaffarian RS, Long MW, Barrett JL, Cradock AL, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Gortmaker SL. Limiting Television to Reduce Childhood Obesity: Cost-Effectiveness of Five Population Strategies. Child Obes. 2021 May 10. doi: 10.1089/chi.2021.0016. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33970695.

The study’s research team, led by Erica Kenney, found that strategies to reduce television exposure could help reduce childhood obesity on a population level. Television watching is one of the strongest risk factors for childhood obesity as children are highly influenced by television advertising and are exposed to many advertisements for unhealthy foods and beverages.

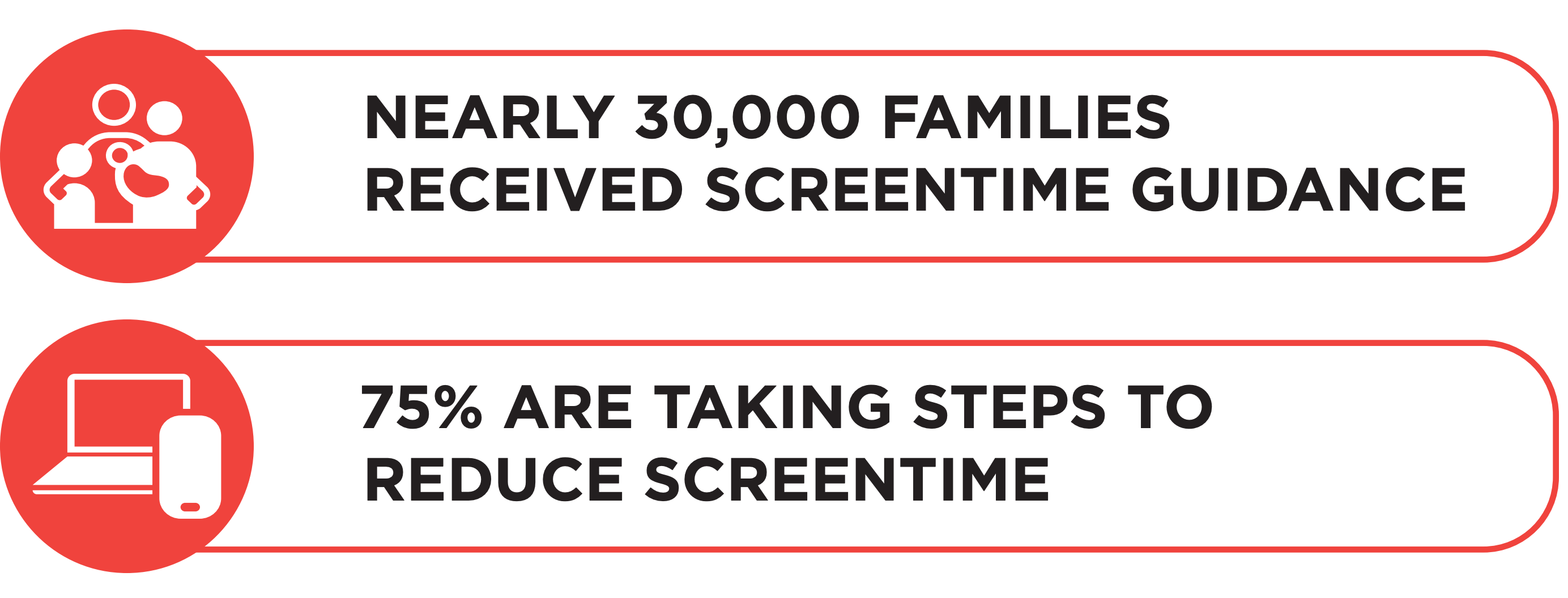

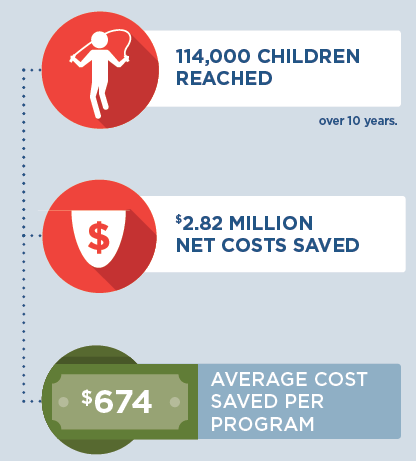

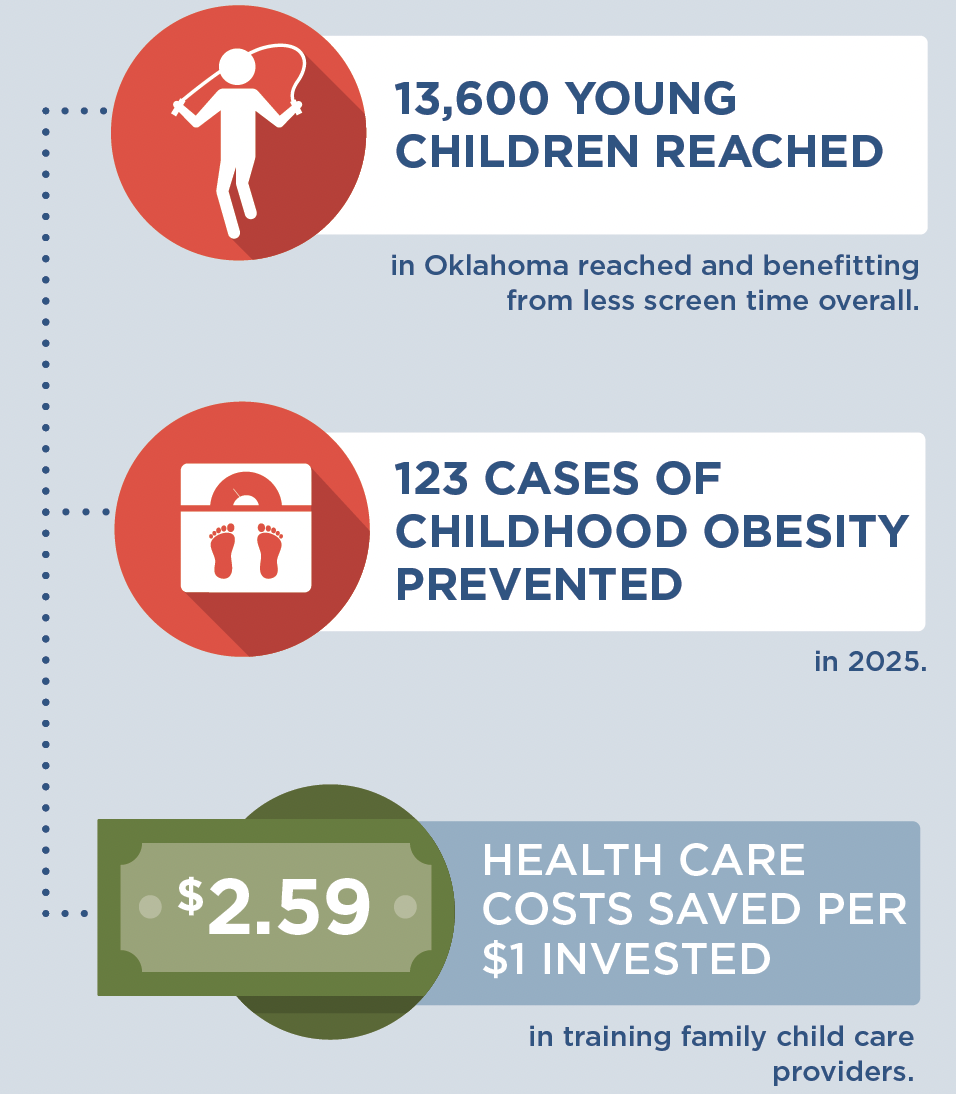

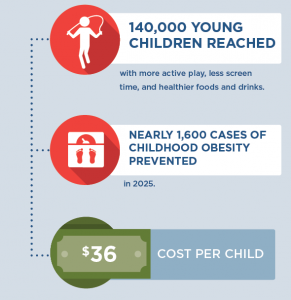

After systematically searching for evidence for intervention strategies that could be effective for reducing children’s TV viewing or advertising exposure if implemented at a population level, the study team used the CHOICES microsimulation model to estimate the cost, population reach, and impact on childhood obesity over 10 years (from 2020-2030) of five potential policy strategies. These strategies included: (1) eliminating the tax deductibility of food and beverage advertising; (2) targeting TV reduction during home visiting programs; (3) motivational interviewing to reduce home television time at Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) clinic visits; (4) adoption of a television-reduction curriculum in child care; and (5) limiting noneducational television in licensed child care settings.

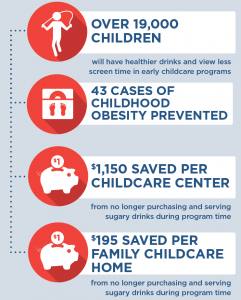

They found that, of the five potential strategies, eliminating the tax benefit to companies of advertising unhealthy foods and beverages to children would reach the most children, prevent the most cases of obesity, and save more in future health care costs than it costs to implement. In addition, incorporating counseling to reduce TV viewing into the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and requiring licensed childcare settings to limit noneducational television were also noted as low-cost, practical intervention strategies. However, these strategies would be limited to young children in those specific settings.

The researchers concluded that strategies to limit television exposure across a range of settings could help contribute to other efforts to prevent childhood obesity in the population at a low cost. Policymakers and public health providers should consider using these kinds of strategies as part of a larger obesity prevention toolkit.

“Policy intervention strategies to reduce exposure to noneducational television time can reduce obesity risk, yet they aren’t widely implemented. This cost-effectiveness modeling study suggests that over 10 years, implementing such strategies could help improve population health at a high value.” – lead author, Erica Kenney