The information in this resource is intended only to provide educational information. This profile describes the estimated benefits, activities, resources, and leadership needed to implement a strategy to improve child health. This information can be useful for planning and prioritization purposes.

- Program to reduce television viewing among young children ages 2-5 in licensed early care and education centers by training educators in an evidence-based curriculum and engaging families in reducing television time at home

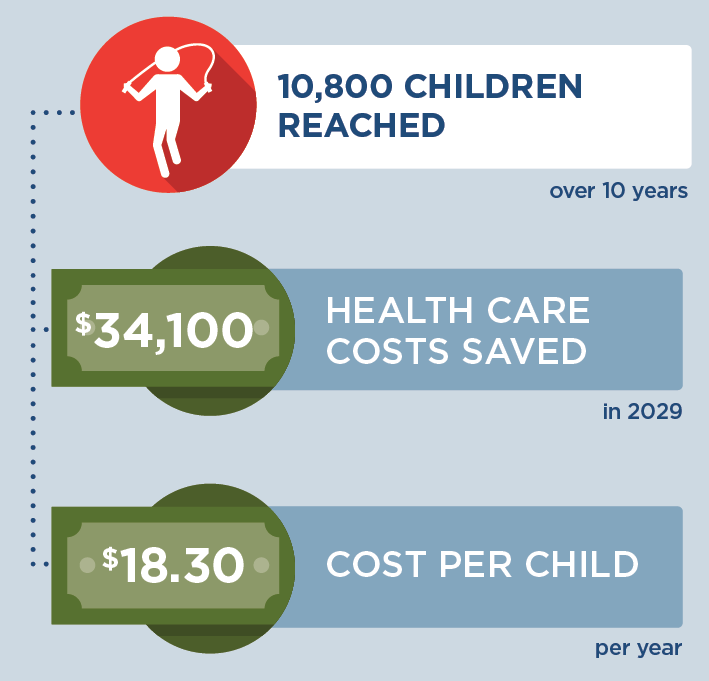

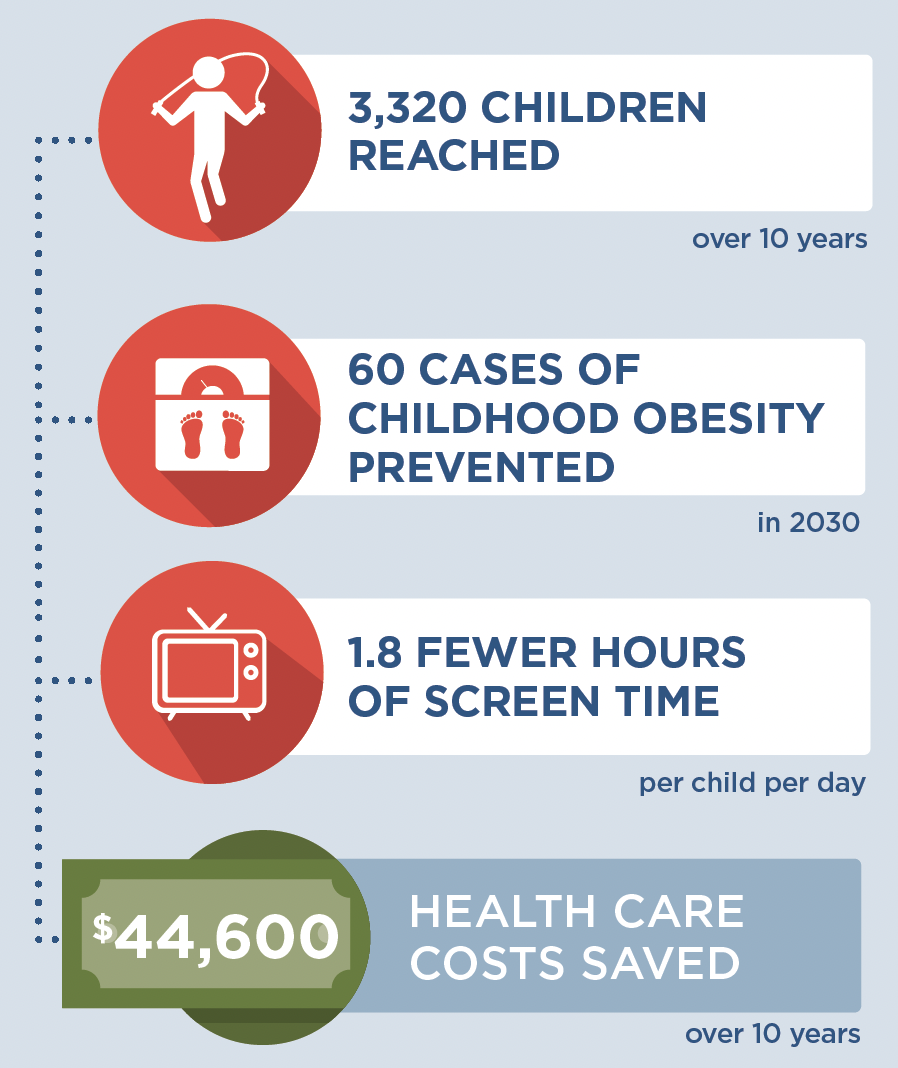

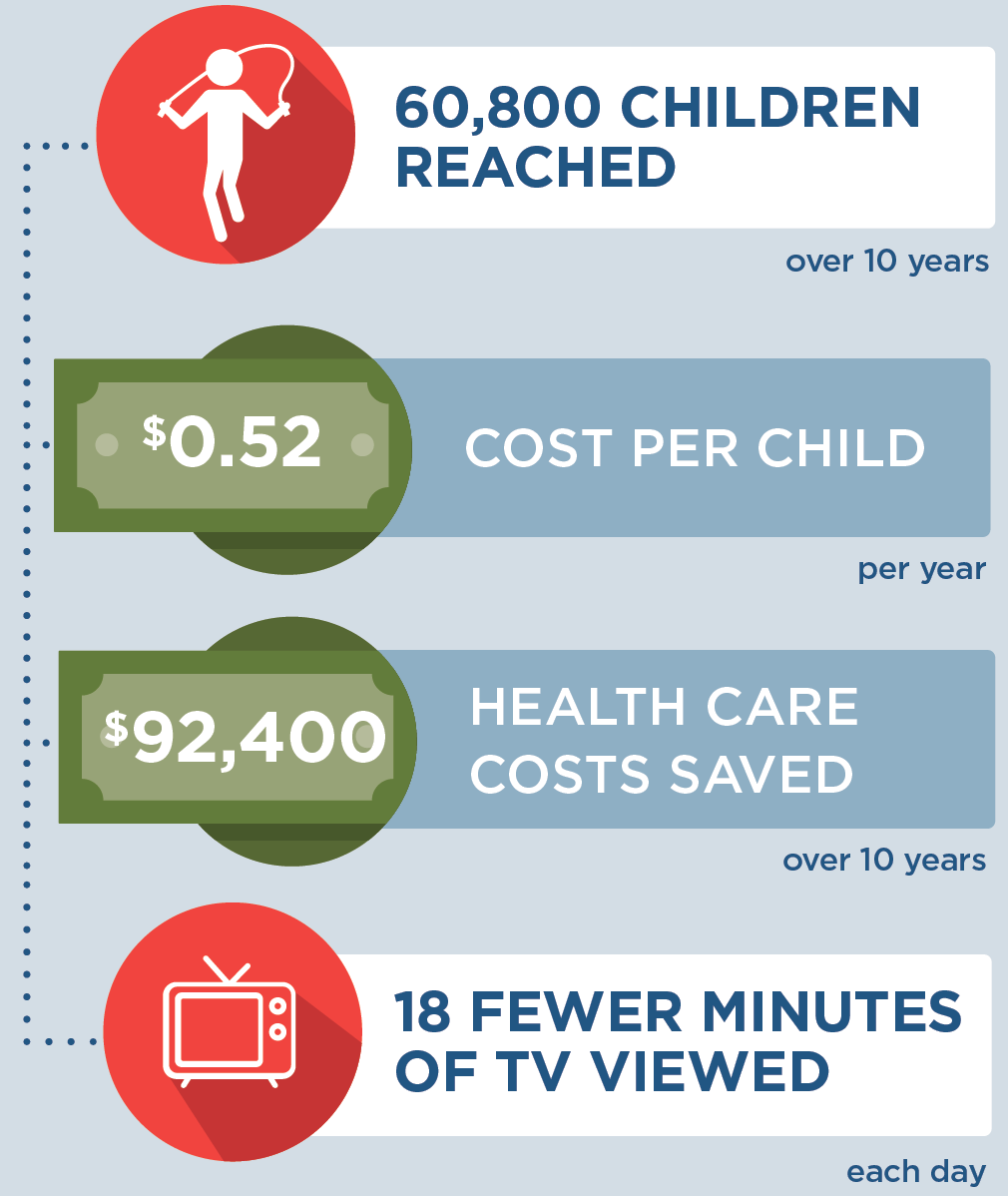

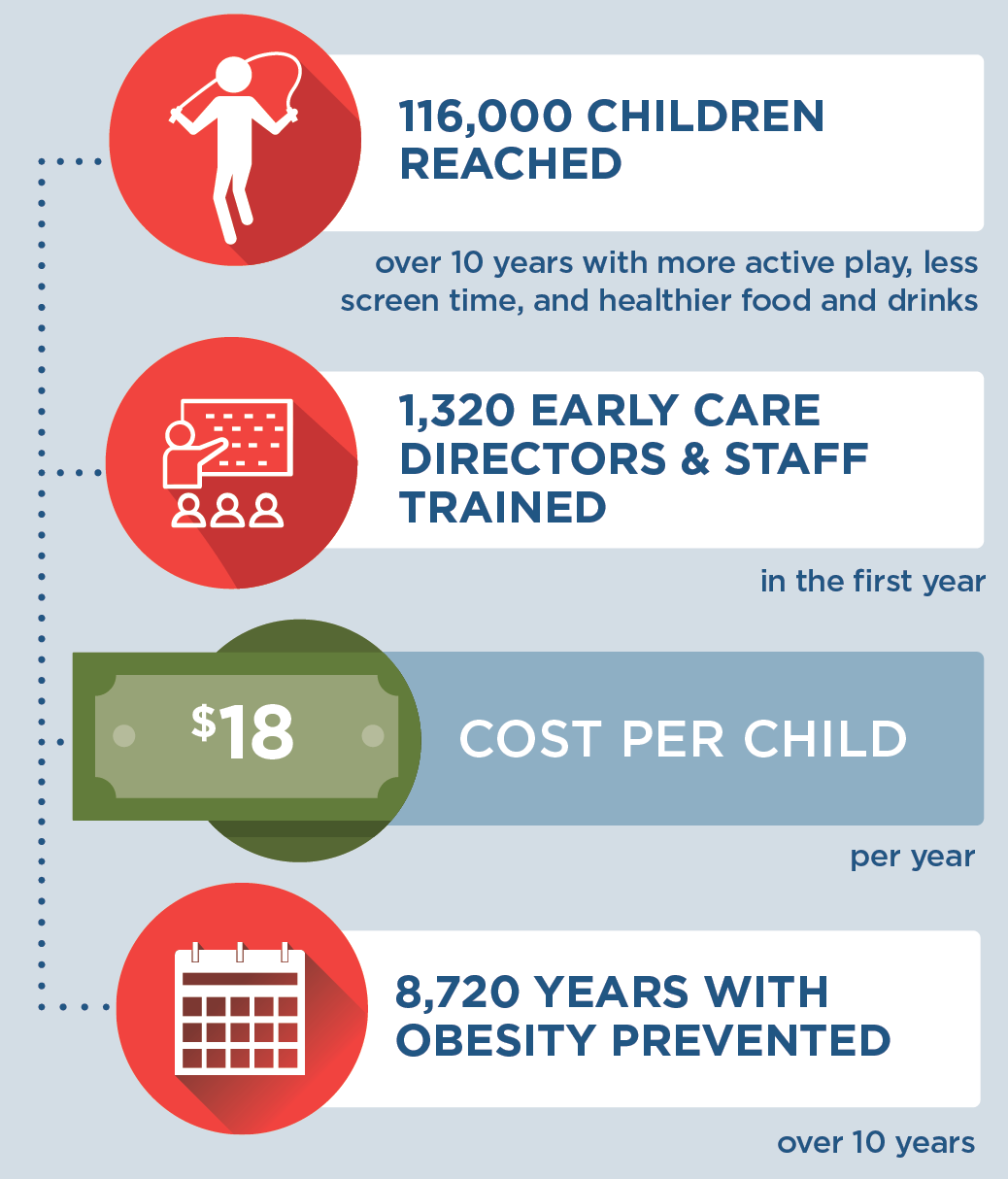

What population benefits?

Children ages 2-5 attending licensed early care and education centers.

What are the estimated benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

Reduce child daily television time which can help promote healthy child weight.

What activities and resources are needed?

| Activities | Resources | Who Leads? |

| Train early care and education directors and staff on an evidence-based curriculum (Fit5Kids) to reduce television time | • Time for state early care and education agency training consultant to prepare for and lead trainings • Time for early care and education program directors and staff to attend trainings • Travel costs |

State early care and education training consultant |

| Provide training materials for early care educators and administrators to engage children and families in reducing television time | • Cost of training materials | State government |

| Provide materials to children and families to promote reduced TV time | • Cost of materials for children and families • Cost of the book “The Berenstain Bears and Too Much TV” |

Early care and education programs |

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Kenney EL, Mozaffarian RS, Long MW, Barrett JL, Cradock AL, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Gortmaker SL. Limiting television to reduce childhood obesity: cost-effectiveness of five population strategies. Child Obes. 2021 Oct;17(7):442-448. doi: 10.1089/ chi.2021.0016.

- Browse more CHOICES research briefs & reports in the CHOICES Resource Library.

- Explore and compare this strategy with other strategies on the CHOICES National Action Kit.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES Strategy Profile: Program in Early Care and Education Settings to Reduce TV Viewing. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; September 2023

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose. The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Adapted from the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist