The information in this brief is intended only to provide educational information.

This brief summarizes a CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership model examining a strategy to incorporate movement breaks, five-to-10-minute physical activity breaks during class time, into school classrooms in Massachusetts.

The Issue

Every child should have opportunities to be physically active. Students who are physically active tend to have better grades,1 attendance in school,1 and stronger muscles and bones.2 Regular physical activity can improve cognition, reduce symptoms of depression, help children maintain a healthy weight, and prevent risk of future chronic disease.2

Experts suggest that schools can provide students with opportunities to be physically active to help meet the national recommendation of 60 minutes per day.2 Incorporating five-to-10-minute movement breaks during class time can supplement other school physical activity opportunities, like physical education and recess. While some Massachusetts public schools offer classroom movement breaks at the middle school level,3 there are little to no data suggesting classroom movement breaks are provided for all younger students. Helping all classroom teachers integrate best practices for movement breaks will ensure more students have an opportunity to be active and help children grow up healthy and ready to learn.

About the Movement Breaks in the Classroom Strategy

To implement this evidence-based strategy,4 the Massachusetts Departments of Public Health and Elementary and Secondary Education would collaborate to connect school districts to the School Wellness Coaching Program. This program helps school districts integrate movement breaks into their local wellness policies and meet state and federal physical activity recommendations. Teachers in kindergarten to fifth-grade classrooms would receive training, technical assistance, and materials to support implementation. School wellness champions could also elect to be trained. This strategy aligns with the School Wellness Coaching Program5 and the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child initiative6 to create school environments that prioritize students’ health, well-being, and ability to learn.

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

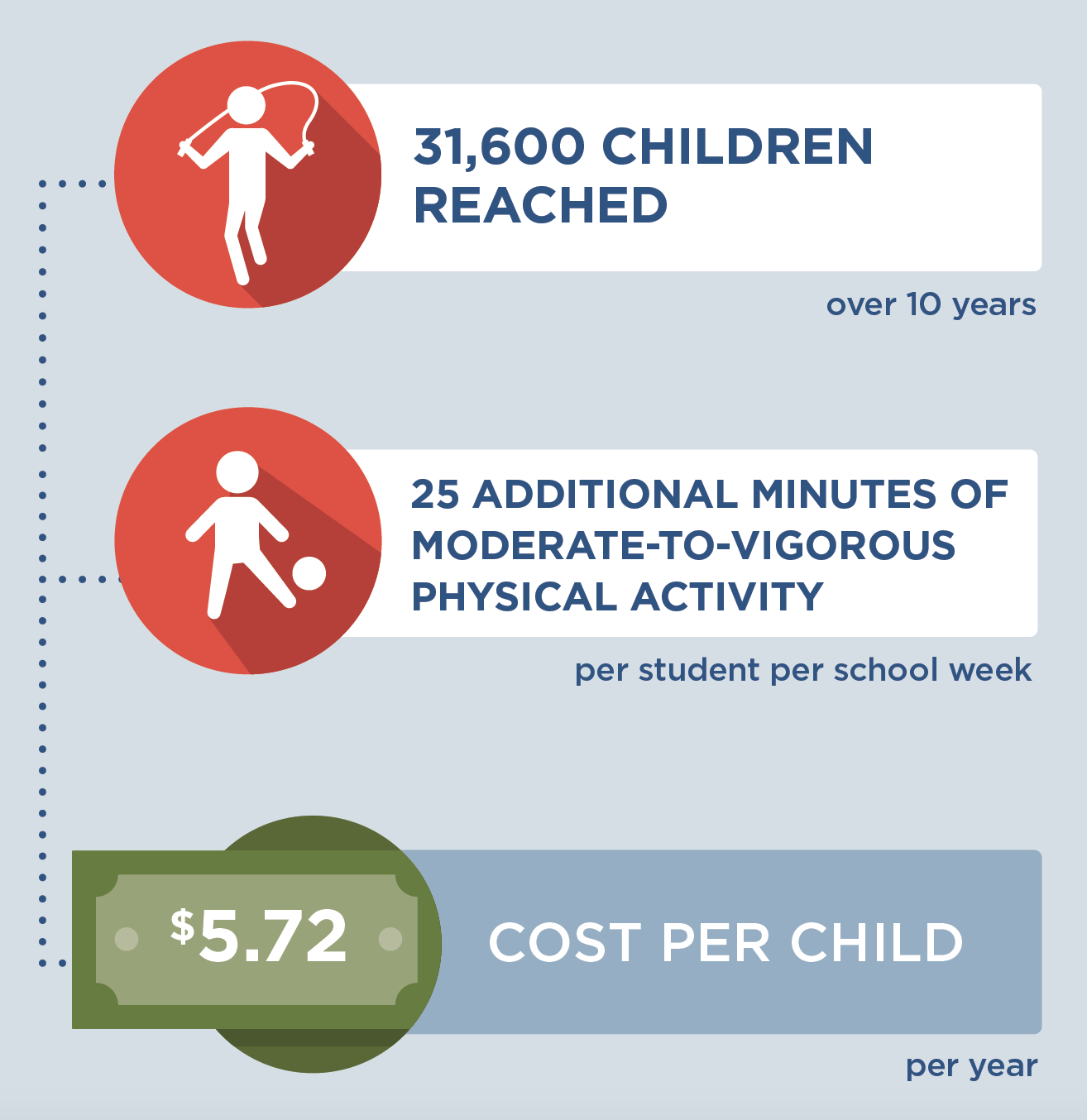

CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes over a 10-year time horizon (2020-2029) of implementing movement breaks in the classroom with the costs and outcomes associated with not implementing the program.

Integrating movement breaks in the classroom is an investment in the future. By the end of 2029: |

Conclusions and Implications

Not all students have access to safe streets, playgrounds, or spaces to be physically active. If movement breaks were incorporated into classrooms in Massachusetts, 31,600 elementary school students would benefit. These students could increase their moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels by 25 minutes per school week, helping them reach the recommended physical activity levels.2 We project that 36 cases of obesity would be prevented in 2029 and $30,800 in health care costs related to excess weight would be saved over 10 years. This strategy would cost less than $6 per child per year to implement in Massachusetts and is likely to be cost-effective at commonly accepted thresholds7 based on net cost per population health improvement related to excess weight ($66,200 per quality-adjusted life year gained).

Classroom movement breaks provide all students with the opportunity to be physically active. This is particularly important for those students with fewer options outside of school. By training and equipping over 200 teachers and other school staff to incorporate movement breaks in the classroom, this strategy could help Massachusetts public schools cultivate a positive school climate and improve social emotional learning.8 Additionally, movement breaks allow students an opportunity for a “brain break” to refocus, reconnect and bring their attention back to their academic work. Students who participate in movement breaks spend more time on task4 and teachers report that students are more engaged, supportive of each other, and responsive to teacher instructions after participating in a movement break.9

Regular physical activity is important for healthy growth and development. Many preventive strategies can play a critical role in helping children establish healthy habits early on in life. Movement breaks provide an opportunity to invest in students and support their healthy growth and academic success.

References

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020-04-21T09:02:35Z 2010.

-

US Dept of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2018. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School Health Profiles 2018: Characteristics of Health Programs Among Secondary Schools. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2019:205. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/profiles/pdf/2018/CDC-Profiles-2018.pdf

-

The Community Preventive Services Task Force. Physical Activity: Classroom-based Physical Activity Break Interventions. The Community Guide; 2021. Accessed Jun 20, 2023. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/tffrs-physical-activity-classroom-based-physical-activity-break-interventions.html

-

School Wellness Initiative for Thriving Community Health (SWITCH). Initiatives: Massachusetts School Wellness Coaching Program. Published 2022. Accessed Oct 5, 2022. https://massschoolwellness.org/initiatives

-

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Student and Family Support (SFS): Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC). Published 2021. Accessed Oct 5, 2022. https://www.doe.mass.edu/sfs/wscc

-

Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC. Updating cost-effectiveness–the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014 Aug 28;371(9):796-7. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1405158. PMID: 25162885.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School-Based Physical Activity Improves the Social and Emotional Climate for Learning. CDC Healthy Schools. Published 2021. Accessed March 9, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/school_based_pa_se_sel.htm

-

Campbell AL, Lassiter JW. Teacher perceptions of facilitators and barriers to implementing classroom physical activity breaks. Journal of Educational Research. 2020;113(2):108-119. DOI: 10.1080/00220671.2020.1752613

Suggested Citation:Good N, Bolton AA, Barrett JL, Reiner JF, Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL. Massachusetts: Movement Breaks in the Classroom {Issue Brief}. The CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; June 2023. For more information, please visit www.choicesproject.org The design for this brief and its graphics were developed by Molly Garrone, MA and partners at Burness. This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health through the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only. This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders. |