The information in this resource is intended only to provide educational information. This profile describes the estimated benefits, activities, resources, and leadership needed to implement a strategy to improve child health. This information can be useful for planning and prioritization purposes.

- Promoting increased water consumption among elementary and middle school students (grades K-8) with the installation of chilled drinking water dispensers in school cafeterias with viable plumbing in schools that participate in the National School Lunch Program.

What population benefits?

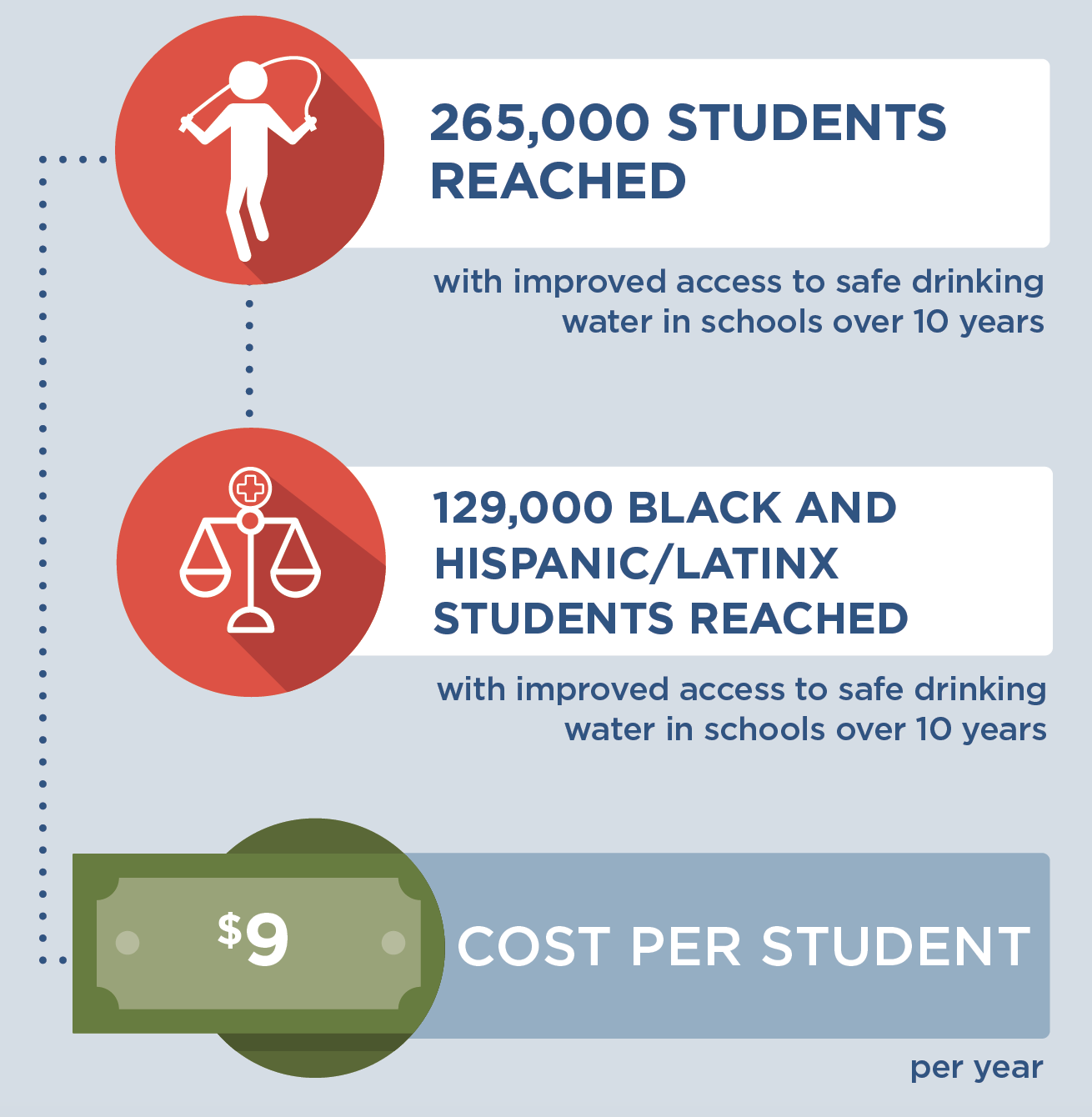

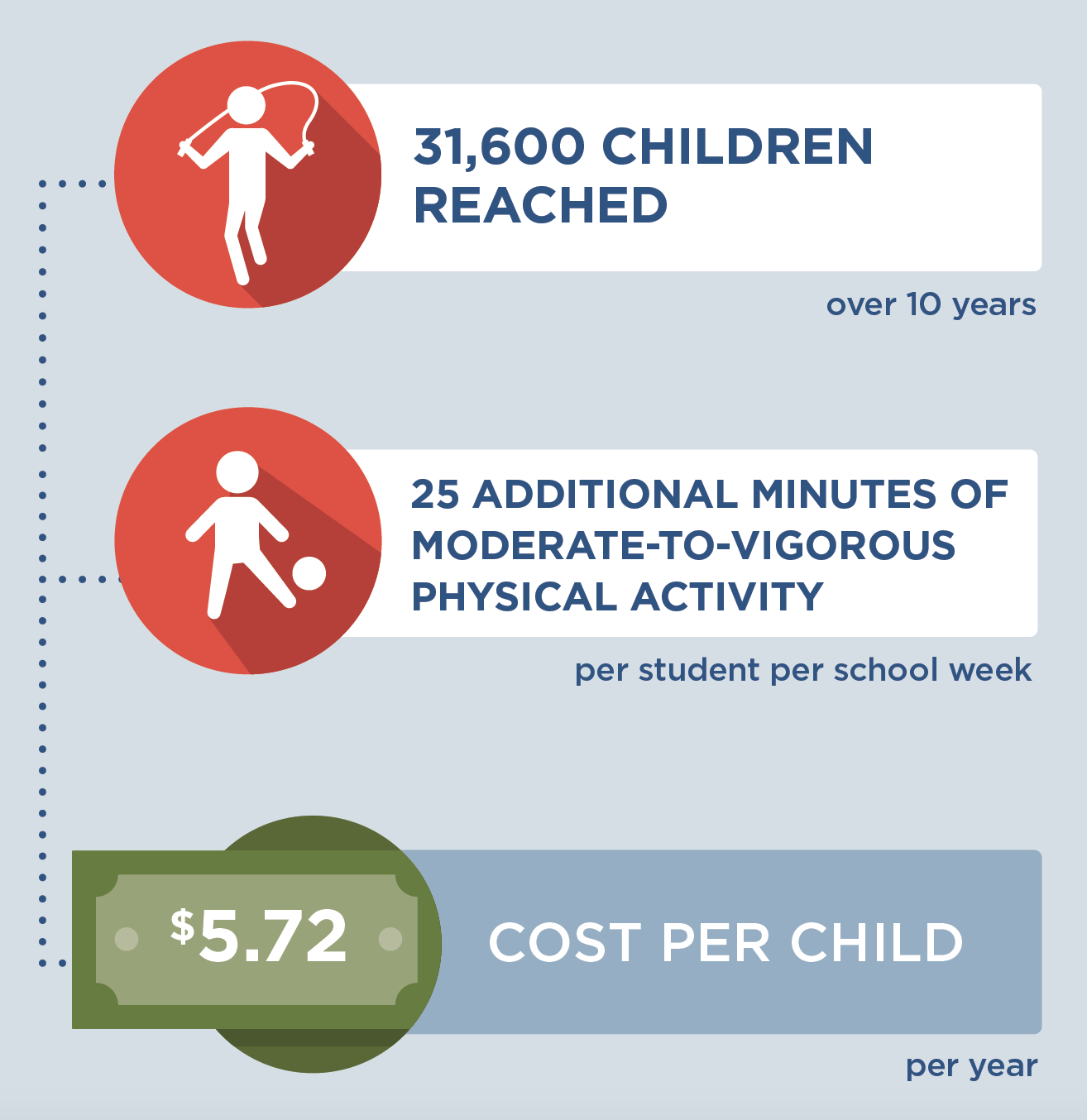

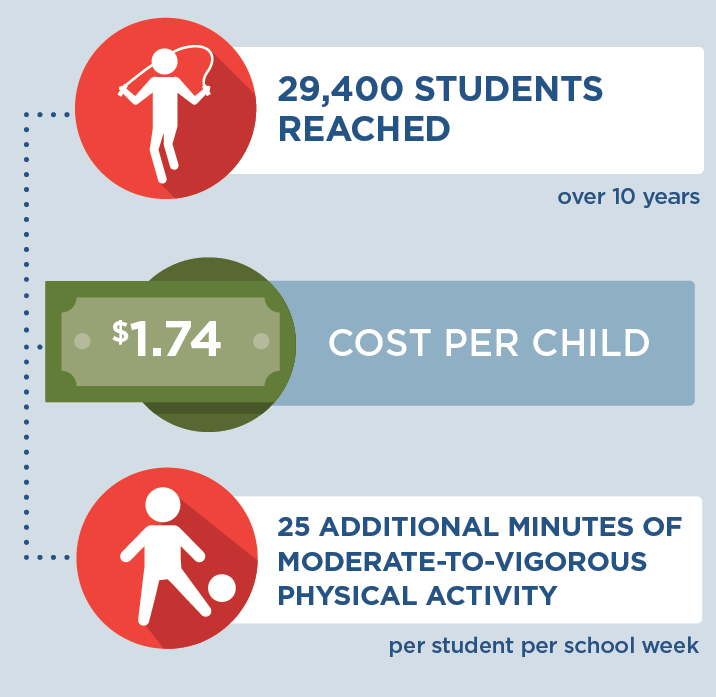

Children in grades K-8 attending schools with viable plumbing that participate in the National School Lunch Program.

What are the estimated benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

Increase the availability of safe, free drinking water in schools. In turn, this would increase child water consumption and promote healthy child weight.

What activities and resources are needed?

| Activities | Resources | Who Leads? |

| Purchase and install chilled water dispensers | • Staffing resources necessary for installing water dispensers • Costs associated with purchasing water dispensers |

School personnel |

| Deliver training to school food service directors in cleaning and maintaining the chilled water dispensers | • Time to develop online training and materials • Time for food service directors to access and attend online training |

School district food service staff |

| Maintain and clean water dispensers | • Time for food service staff to clean water dispensers • Cost of water dispenser filter replacement • Time for food service staff to replace filters |

School food service staff |

| Increase utilities and disposable cup usage | • Cost of incremental increase in water and electricity usage • Cost of increased disposable cup usage |

Schools |

| Test lead levels in drinking water and remediate issues | • Cost of lead testing and remediation for school drinking water | Schools |

| Conduct administrative review related to drinking water | • Time for the school district food service director to participate in administrative review • Time for the National School Lunch Program administrator to conduct administrative review |

State government |

Strategy Modification

Some state and local health agencies added to this strategy the costs of developing and disseminating educational materials on water consumption to further encourage water consumption among students. This would require additional time to develop and disseminate the educational materials and the additional cost of the educational materials.

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Kenney EL, Cradock AL, Long MW, Barrett JL, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Gortmaker SL. CostEffectiveness of Water Promotion Strategies in Schools for Preventing Childhood Obesity and Increasing Water Intake. Obesity. 2019;27(12):2037-2045. doi:10.1002/oby.22615.

Selected CHOICES research brief including cost-effectiveness metrics:

Gouck J, Whetstone L, Walter C, Pugliese J, Kurtz C, Seavey-Hultquist J, Barrett J, McCulloch S, Reiner J, Cradock AL. California: Improving Drinking Water Equity and Access in California Schools {Issue Brief}. California Department of Public Health, Sacramento, CA, the County of Santa Clara Public Health Department, San Jose, CA, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; December 2021. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-water-schools-california

McCulloch SM, Barrett JL, Reiner JF, Cradock AL. Massachusetts: Water Dispensers in Schools {Issue Brief}. The CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; June 2023. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-water-dispensers-ma

- Browse more CHOICES research briefs & reports in the CHOICES Resource Library.

- Explore and compare this strategy with other strategies on the CHOICES National Action Kit.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES Strategy Profile: Promoting Water Consumption in Schools. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; April 2022; revised August 2023.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose. The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Adapted from the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist