The information in this brief is intended only to provide educational information.

This brief summarizes a CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership model examining a policy to promote healthy beverage choices in licensed out-of-school time (OST) programs in Wisconsin.

The Issue

All children should have opportunities to grow up at a healthy weight. However, consuming sugary drinks, like sports drinks, soda, and fruit drinks sweetened with sugar, poses a health risk to children. In 2012, almost one in four (23.1%) adolescents in Wisconsin drank a sugary drink at least once a day.1

In Wisconsin, more than 120,000 children attend OST programs.2 These educational settings can provide essential opportunities for children to learn healthy eating habits. However, many OST programs in Wisconsin do not provide guidance to children or their families about the types of beverages that should be brought in to drink while children participate in program activities. Many programs must meet high national nutrition standards for the foods and beverages they serve to kids. However, when children bring in their own drinks, they can be less healthy than options served by the programs they attend.3 Promoting only healthy beverage choices in OST programs may improve children’s health by reducing sugary drink consumption.4,5

About the Healthy Beverage Policy

We looked at a strategy that would support OST programs in adopting a healthy beverage policy. Programs that participate in YoungStar, Wisconsin’s childcare quality rating and improvement system, and receive their snacks through meal programs that meet national nutrition standards, were considered the subset of eligible sites. A healthy beverage policy would set nutritional standards for the beverages that could be brought into the OST programs, ensuring that all beverages available in these programs meet national standards that support good nutrition.3 Implementation would include training and informing OST program directors about the need for policy change and ways to incorporate the new policy into their program handbooks. YoungStar Technical Consultants would provide technical assistance to support policy adoption, and program staff would complete surveys annually to monitor policy implementation.

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

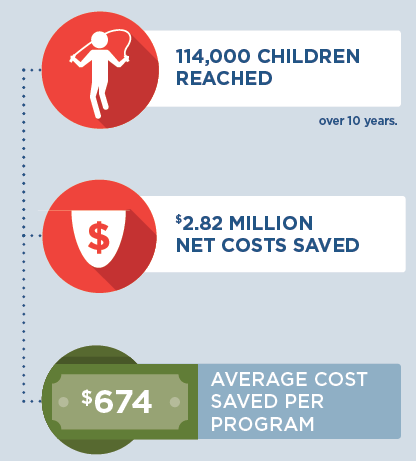

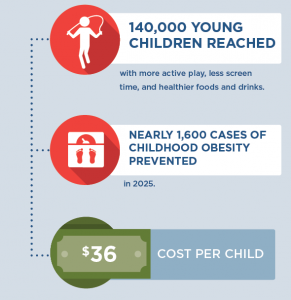

A CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes of implementing a healthy beverage policy in OST programs with the costs and outcomes associated with not implementing the healthy beverage policy over 10 years (2020-2030).

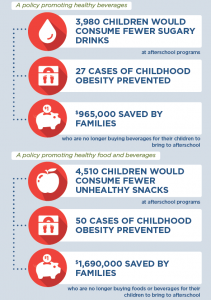

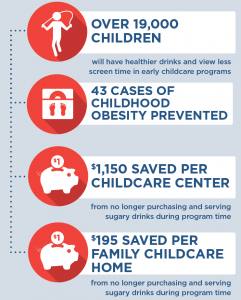

|

Implementing a healthy beverage policy in programs in Wisconsin could support good nutrition and save families money. By the end of 2030: |

Conclusions and Implications

Adopting a healthy beverage policy in OST programs in Wisconsin could promote better health for children and save families money. Over 10 years, this strategy could support 145 programs in creating healthier environments for the more than 33,000 children they will serve. This would cost less than a dollar per child participating in these OST programs per year. Over 10 years, 2,060 children would be consuming 10 fewer ounces of sugary drinks per day on the days they attend the OST program. Over 10 years, this could amount to $555,000 in savings for families who no longer buy sugary beverages for their children to bring into OST programs. Consuming fewer sugary drinks can promote better oral health,6 and prevent more children from having obesity.4 In 2030 alone, it is expected there will be 15 fewer cases of obesity if Wisconsin OST programs implemented healthy beverage policies.

OST programs can play a critical role in helping children establish healthy nutritional habits early on in life. Many providers want to offer an environment that nurtures healthy children, but some programs may need support to integrate new nutrition standards. YoungStar can provide training and resources to help OST program providers adopt nutrition standards that reinforce healthy nutrition habits.7 With training on nutritional standards, OST program directors and program staff would also have the opportunity to learn about and adopt healthier eating habits as well.8 A healthy beverage policy could support OST providers in providing healthier program settings for children in the hours outside of school.

References

-

CDC, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity. Wisconsin: State Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity Profile. Published September 2012. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/stateprograms/fundedstates/pdf/wisconsin-state-profile.pdf

-

Marshfield Clinic Center for Community Outreach. Afterschool in Wisconsin: Building Our Children’s Future, One Program at a Time. https://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/educ/Wisconsin_infographic.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2020.

-

Kenney EL, Austin SB, Cradock AL, Giles CM, Lee RM, Davison KK, Gortmaker SL. Identifying sources of children’s consumption of junk food in Boston afterschool programs, April-May 2011. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014 Nov 20;11:E205.

-

Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84(2):274– 88.

-

Khan LK, Sobush K, Keener D, Goodman K, Lowry A, Kakietek J, et al. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2009;58(RR-7):1–26.

-

Sheiham A, James WPT. A new understanding of the relationship between sugars, dental caries and fluoride use: implications for limits on sugars consumption. Public Health Nutrition. 2014;17(10):2176-2184.

-

Wisconsin Department of Children and Families. YoungStar Training and Professional Development. https://dcf.wisconsin.gov/youngstar/providers/training. Accessed January 6, 2021.

-

Weaver RG, Beets MV, Saunders RP, Beighle A, Webster C. A Comprehensive Professional Development Training’s Effect on Afterschool Program Staff Behaviors to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice. 2014;20(4):E6-E14.

Suggested Citation:Salas TM, Meinen A, Kim H, McCulloch S, Reiner J, Barrett J, Cradock AL. Wisconsin: Supporting Healthy Beverage Choices in Out-of-School Time Programs {Issue Brief}. Wisconsin Department of Health Services & University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; May 2021. For more information, please visit www.choicesproject.org |

Funding for the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW) was provided by the Wisconsin Partnership Program PERC Award (233 AAG9971). The authors would also like to thank the University of Wisconsin Survey Center, SHOW administrative, field, and scientific staff, as well as all the SHOW participants for their contributions to this study.

The design for this brief and its graphics were developed by Molly Garrone, MA and partners at Burness.

This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only. This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.