The information in this resource is intended only to provide educational information. This profile describes the estimated benefits, activities, resources, and leadership needed to implement a strategy to improve child health. This information can be useful for planning and prioritization purposes.

- Improving nutrition, physical activity, & screen time policies & practices for children ages 3-5 by incorporating the Nutrition & Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) Program into state’s Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS) for early care and education programs.

What population benefits?

Children ages 3-5 attending licensed early care and education programs that participate in their state’s Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS).

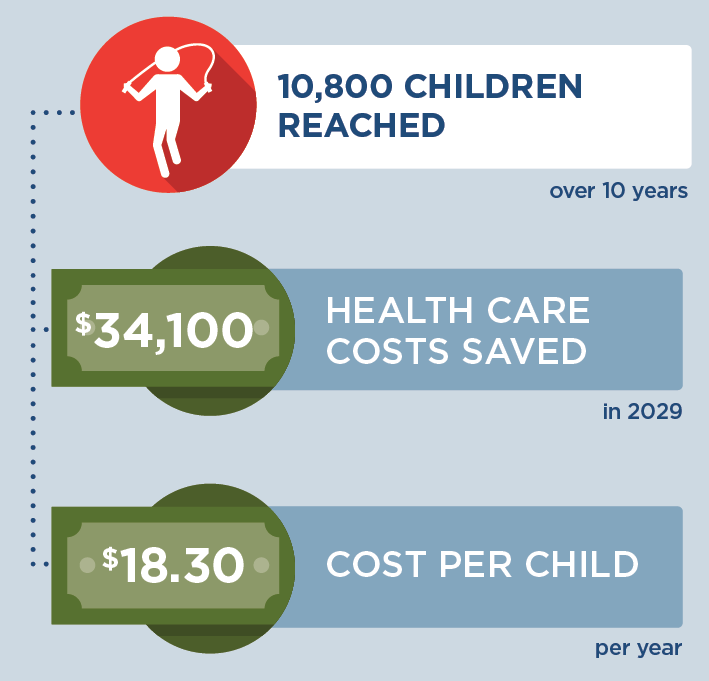

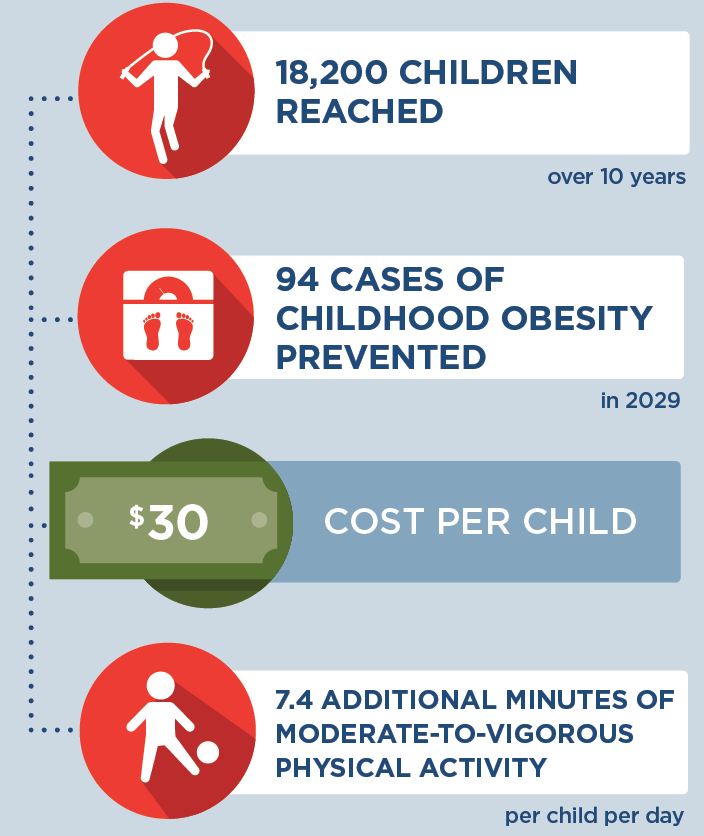

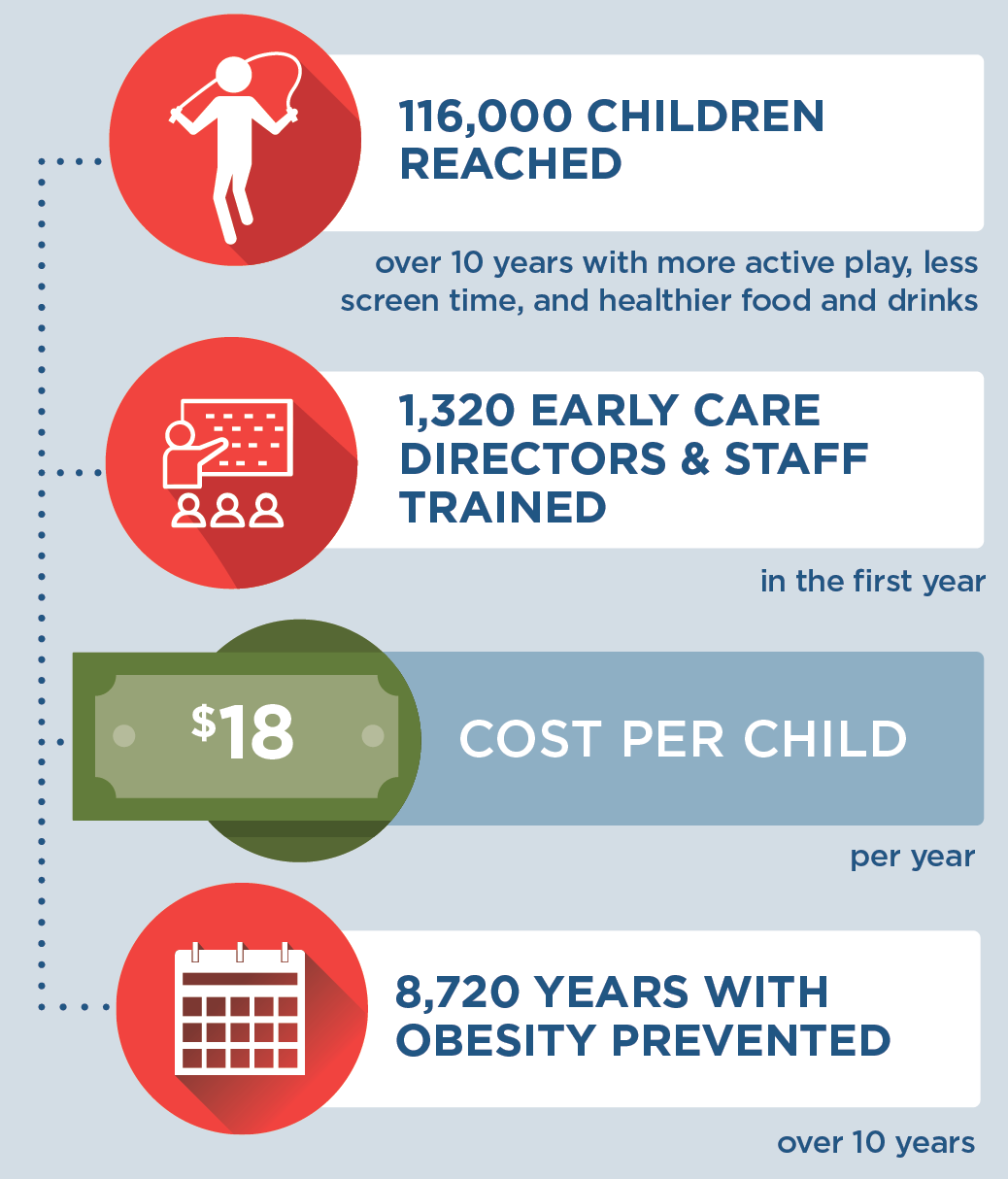

What are the estimated benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

Promote healthy child weight.

What activities and resources are needed?

| Activities | Resources | Who Leads? |

| Train early care and education health professionals to work with early care and education programs | • Time of state training consultant to train early care and education health professionals • Time of early care and education health professionals to be trained |

State QRIS administrators |

| Provide consultation to early care and education program directors and staff for conducting self-assessments of program policies and practices, completing action plans, and implementing changes to improve nutrition, physical activity, and screen time environments in programs | • Time of early care and education health professionals to provide consultation to early care and education programs • Time of early care and education program directors and staff to participate in consultation |

Early care and education health professionals |

| Provide materials and equipment for implementing NAP SACC program | • Cost for GO NAP SACC online license • Physical activity equipment costs |

State QRIS administrators |

| Implement changes in early care and education programs to improve nutrition, physical activity, and screen time environments | • Time of early care and education program directors to implement changes | Early care and education program directors |

| Improve nutritional quality of meals served in early care and education programs | • Food costs for improving nutritional quality of meals | Early care and education program directors |

| Monitor compliance with NAP SACC program | • Time of state-level QRIS Administrators to monitor compliance | State QRIS administrators |

Strategy Modification

In states where NAP SACC is already being implemented, the strategy could be modified to focus on increasing the number of early care and education programs that participate in NAP SACC. With this modification, the cost for the GO NAP SACC online license would not be needed, since it is a fixed annual cost paid per state (i.e., it does not depend on the number of participating programs). With this modification, the impact on health is expected to be similar, and the impact on reach and cost would vary according to the number of programs reached.

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Gortmaker SL, Wang YC, Long MW, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Barrett JL, Kenney EL, Sonneville KR, Afzal AS, Resch SC, Cradock AL. Three interventions that reduce childhood obesity are projected to save more than they cost to implement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015 Nov;34(11):1932-9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0631. Supplemental Appendix with strategy details available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/suppl/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0631/ suppl_file/2015-0631_gortmaker_appendix.pdf

Selected CHOICES research brief including cost-effectiveness metrics:

Adams B, Sutphin B, Betancourt K, Balamurugan A, Kim H, Bolton A, Barrett J, Reiner J, Cradock AL. Arkansas: Creating Healthier Child Care Environments: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) in the Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS) {Issue Brief}. Arkansas Department of Health, Little Rock, AR, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; May 2021. Available at: https://choicesproject.org/publications/brief-napsacc-arkansas

Kenney EL, Giles CM, Flax CN, Gortmaker SL, Cradock AL, Ward ZJ, Foster S, Hammond W. New Hampshire: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) Intervention {Issue Brief}. New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Concord, NH, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; October 2017. Available at: https:// choicesproject.org/publications/brief-napsacc-intervention-new-hampshire

- Browse more CHOICES research briefs & reports in the CHOICES Resource Library.

- Explore and compare this strategy with other strategies on the CHOICES National Action Kit.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES Strategy Profile: Creating Healthier Early Care and Education Environments. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; September 2023.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose. The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Adapted from the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist