The information in this resource is intended only to provide educational information. This profile describes the estimated benefits, activities, resources, and leadership needed to implement a strategy to improve child health. This information can be useful for planning and prioritization purposes.

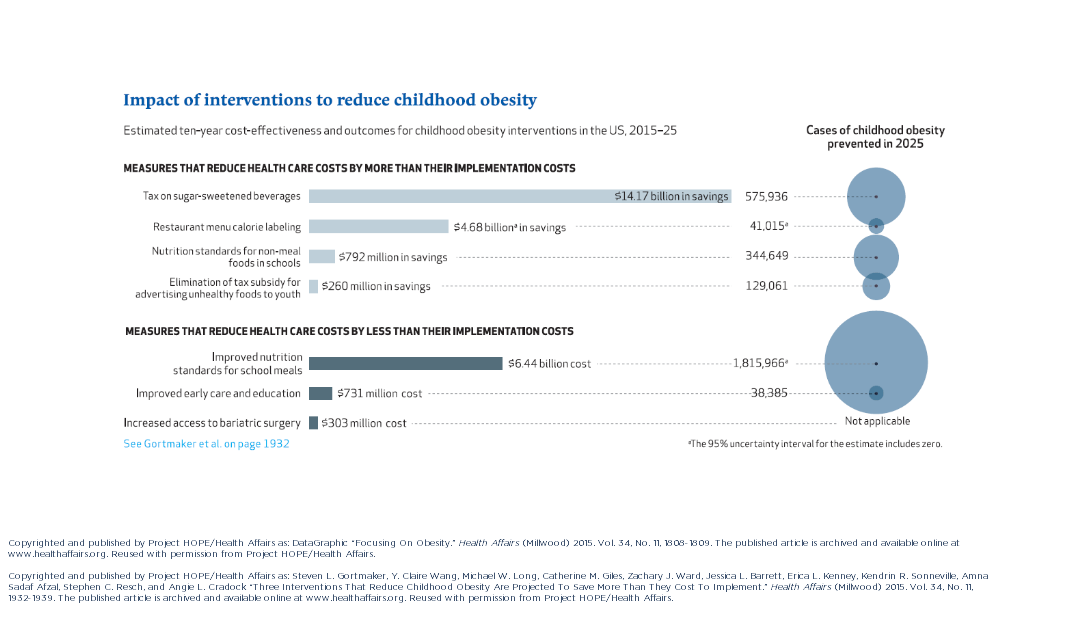

- Reducing exposure to unhealthy food and beverage advertising is a strategy to eliminate the tax deductibility of television advertising costs for nutritionally poor foods and beverages advertised to children and adolescents ages 2-19.

What population benefits?

All youth and adolescents between the ages of 2 and 19.

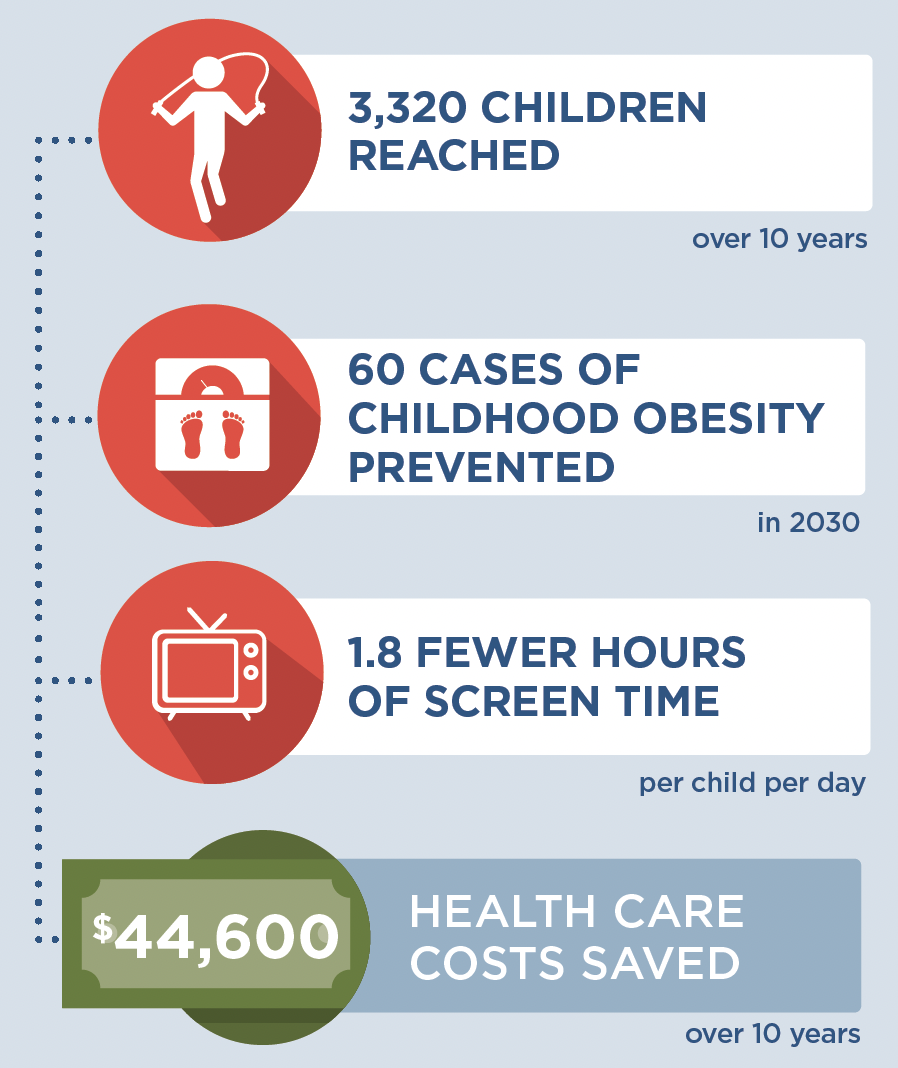

What are the estimated benefits?

Relative to not implementing the strategy

Reduce exposure to unhealthy food and beverage advertising on television and, in turn, promote healthy weight.

What activities and resources are needed?

| Activities | Resources | Who Leads? |

| Process tax statements and conduct audits | • Time for the state tax administrator to process tax statements and conduct audits | State tax administrator |

| Prepare tax statements and participate in audits | • Time for a private company tax accountant to prepare tax statements and participate in audits | Private company tax accountant |

FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Kenney EL, Mozaffarian RS, Long MW, Barrett JL, Cradock AL, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Gortmaker SL. Limiting television to reduce childhood obesity: cost-effectiveness of five population strategies. Child Obes. 2021 Oct;17(7):442-448. doi: 10.1089/chi.2021.0016.

- Browse more CHOICES research briefs & reports in the CHOICES Resource Library.

- Explore and compare this strategy with other strategies on the CHOICES National Action Kit.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES Strategy Profile: Reducing Exposure to Unhealthy Food and Beverage Advertising. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; September 2023.

Funding

This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose. The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.

Adapted from the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist

“By changing the tax treatment of advertising expenses, the food industry will have less incentive to advertise unhealthy foods and drinks to kids,” says lead author Kendrin Sonneville, ScD, RD, Director of Nutrition Training in the Division of Adolescent Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“By changing the tax treatment of advertising expenses, the food industry will have less incentive to advertise unhealthy foods and drinks to kids,” says lead author Kendrin Sonneville, ScD, RD, Director of Nutrition Training in the Division of Adolescent Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital.