Long MW, Ward ZJ, Resch SC, Cradock AL, Wang YC, Giles CM, Gortmaker SL. State-level estimates of childhood obesity prevalence in the United States corrected for report bias. Int J Obes (Lond). Epub 2016 Jul 27.

Abstract

Background/objectives

State-specific obesity prevalence data are critical to public health efforts to address the childhood obesity epidemic. However, few states administer objectively measured body mass index (BMI) surveillance programs. This study reports state-specific childhood obesity prevalence by age and sex correcting for parent-reported child height and weight bias.

Subjects/methods

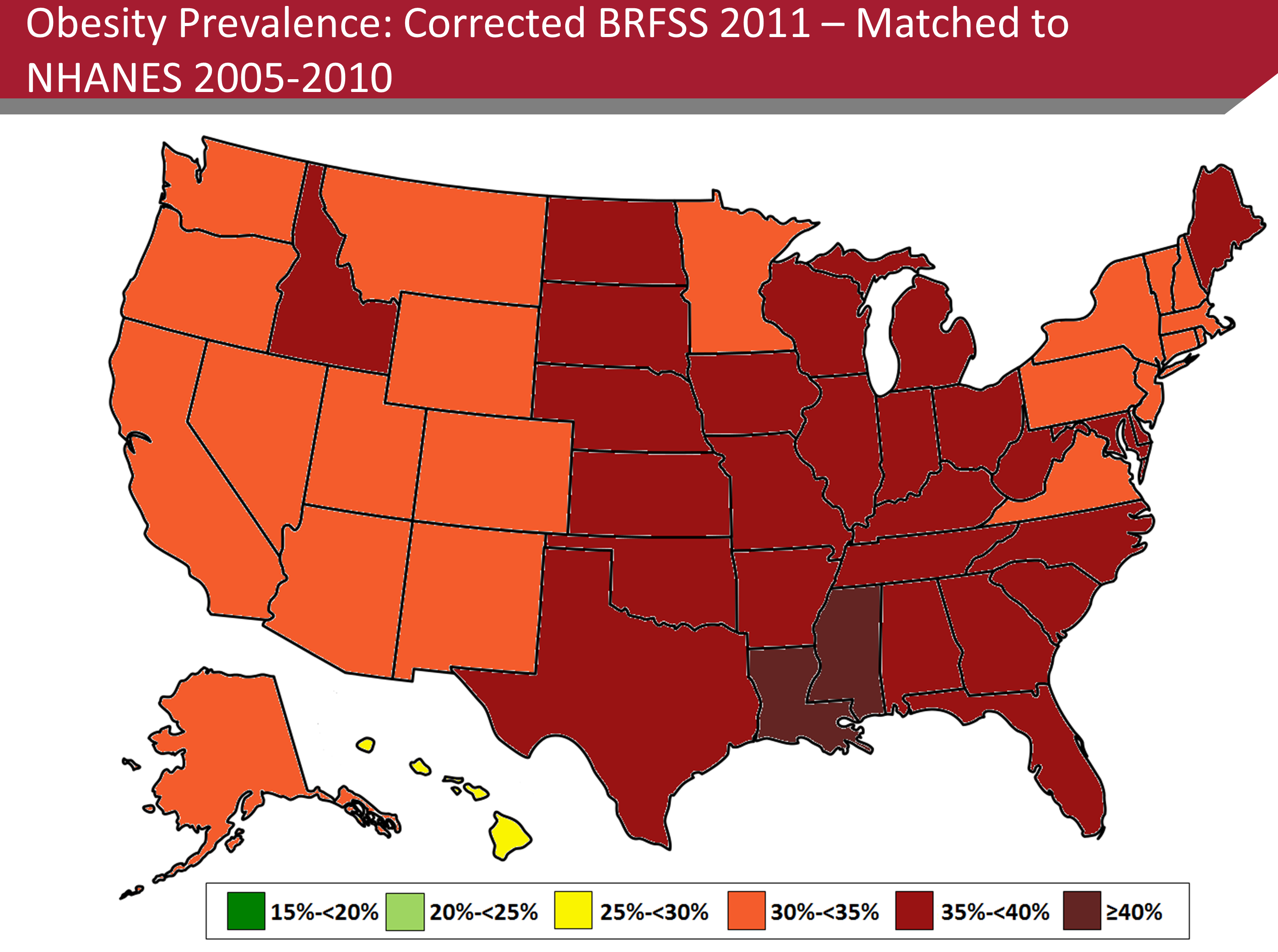

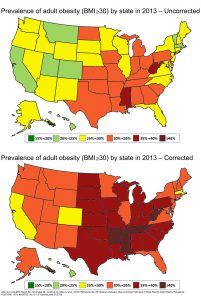

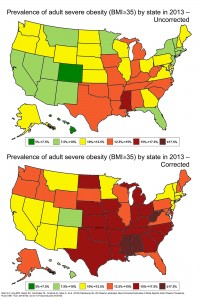

As part of the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost Effectiveness Study (CHOICES), we developed childhood obesity prevalence estimates for states for the period 2005-2010 using data from the 2010 US Census and American Community Survey (ACS), 2003-2004 and 2007-2008 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) (n=133 213), and 2005-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) (n=9377; ages 2-17). Measured height and weight data from NHANES were used to correct parent-report bias in NSCH using a non-parametric statistical matching algorithm. Model estimates were validated against surveillance data from five states (AR, FL, MA, PA and TN) that conduct censuses of children across a range of grades.

Results

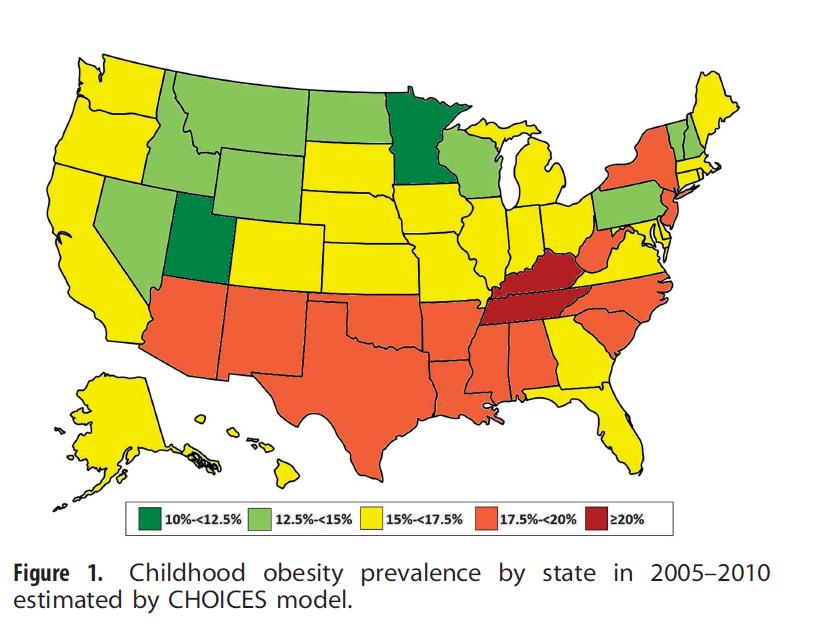

Parent-reported height and weight resulted in the largest overestimation of childhood obesity in males ages 2-5 years (NSCH: 42.36% vs NHANES: 11.44%). The CHOICES model estimates for this group (12.81%) and for all age and sex categories were not statistically different from NHANES. Our modeled obesity prevalence aligned closely with measured data from five validation states, with a 0.64 percentage point mean difference (range: 0.23-1.39) and a high correlation coefficient (r=0.96, P=0.009). Estimated state-specific childhood obesity prevalence ranged from 11.0 to 20.4%.

Conclusion

Uncorrected estimates of childhood obesity prevalence from NSCH vary widely from measured national data, from a 278% overestimate among males aged 2-5 years to a 44% underestimate among females aged 14-17 years. This study demonstrates the validity of the CHOICES matching methods to correct the bias of parent-reported BMI data and highlights the need for public release of more recent data from the 2011 to 2012 NSCH.

“Full day childcare programs are an educational environment responsible for providing children with snacks, meals, and daily opportunities for physical activity,” says lead author, Davene Wright, PhD, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine. “Many childcare programs fail to meet best practice standards for nutrition, physical activity, and screen time viewing. When 20 percent of preschool-aged children in the US are currently overweight or obese, this sector should be a key target for policy regulations to aid in the development of lifelong healthy behaviors.”

“Full day childcare programs are an educational environment responsible for providing children with snacks, meals, and daily opportunities for physical activity,” says lead author, Davene Wright, PhD, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine. “Many childcare programs fail to meet best practice standards for nutrition, physical activity, and screen time viewing. When 20 percent of preschool-aged children in the US are currently overweight or obese, this sector should be a key target for policy regulations to aid in the development of lifelong healthy behaviors.”