The information in this brief is intended only to provide educational information.

This brief summarizes a CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership model examining a strategy incorporating the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) assessment tools into Better Beginnings, Arkansas’ Quality Rating and Improvement System, to support quality early child care program opportunities and promote child health.

The Issue

In Arkansas, three out of 10 kindergarteners entering school in 2018 had overweight or obesity.1 The majority of today’s children will have obesity at age 35 if we don’t act.2 Making sure children are growing up at a healthy weight from their very first days is a critical way to prevent obesity and future risk for obesity-related diseases like diabetes as adults. Conditions linked to obesity, previously only seen in adults, are appearing in Arkansas’ Medicaid-enrolled children.3 Early child care programs that support healthy nutrition and physical activity habits show great promise in promoting healthy weight.4

In Arkansas, more than half of children ages 2-5 attend a licensed child care program.5 Providing licensed child care programs with training opportunities and resources through Better Beginnings may be an effective strategy to improve the quality of child care programs and to ensure that the majority of children in Arkansas are off to a healthy start.

About NAP SACC

NAP SACC is an evidence-based, trusted strategy enabling child care centers to attain best practices regarding nutrition, active play, and screen time.4 To date, NAP SACC shows the best evidence for reducing childhood obesity risk in children under age 5.6 Early education program directors and staff complete self-assessments and receive training and technical assistance to implement practices, policies, and changes supporting healthy outcomes. Better Beginnings is designed to improve child care environments to support child health and development. Integrating NAP SACC into Better Beginnings can improve the quality of child care programs and ensure more children grow up healthy in Arkansas.

Comparing Costs and Outcomes

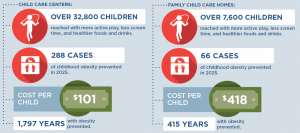

A CHOICES cost-effectiveness analysis compared the costs and outcomes over a 10-year time horizon (2020-2030) of implementing NAP SACC with the costs and outcomes of not implementing the program.

|

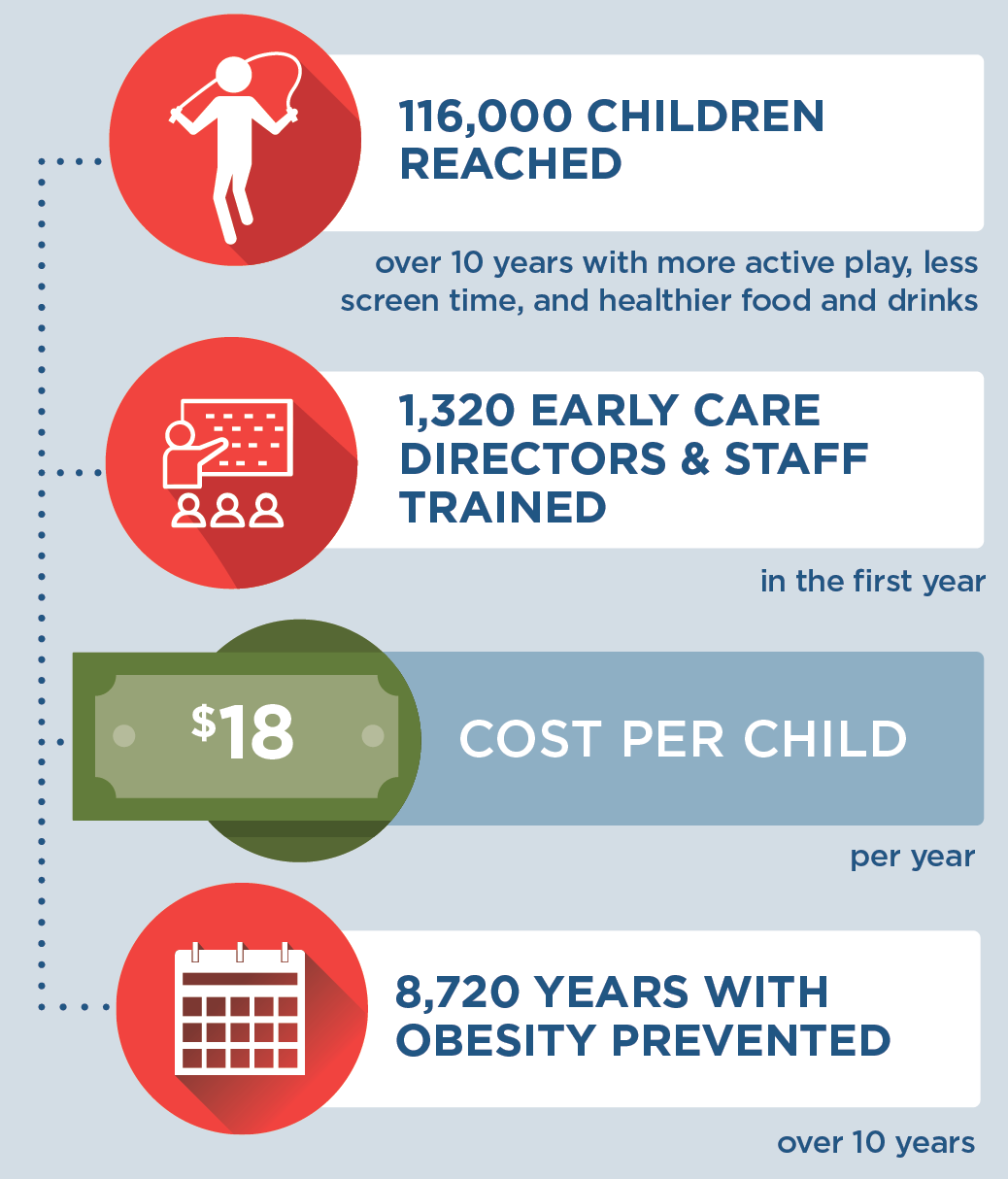

Implementing NAP SACC into Better Beginnings in Arkansas is an investment in child health. By the end of 2030: |

Conclusions and Implications

Every child should have opportunities for a healthy start. A state-level initiative integrating NAP SACC into training and quality improvement through Better Beginnings could create healthier nutrition and physical activity environments in child care programs for 116,000 children over 10 years. This strategy would benefit 1,320 early care directors and staff with training and technical assistance to support using nutrition, active play, and screen time best practices at 659 child care programs. Over 10 years, children in Arkansas would have 8,720 more years lived at a healthy weight and 1,130 fewer children would have obesity in 2030 alone.

Many prevention strategies targeting children require an upfront investment because costly obesity-related health conditions generally present later in adulthood.7 While we project this strategy would cost $18 per child per year, shortchanging early prevention efforts may lead to costly and complicated treatment in the future. Already, the total annual costs of having obesity are estimated to be $6 million for the 30,000 25- to 29-year-olds enrolled in Medicaid—inclusive of Arkansas’ expansion population. This represents an excess annual cost of $200 per person due to obesity.3

Early child care programs also play a critical role in supporting healthy child development and children’s academic readiness.8 Investing in a strategy for quality improvement that provides the necessary training, technical assistance, and resources supports early educators in providing high-quality child care that nurtures healthy habits. Enabling early education leaders in Arkansas to use the best available evidence to prevent excess weight gain in children will support children’s healthy growth and development.

References

-

ACHI. (2019). Assessment of Childhood and Adolescent Obesity in Arkansas: Year 16 (Fall 2018–Spring 2019). Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. Little Rock, AR.

-

Ward Z, Long M, Resch S, Giles C, Cradock A, Gortmaker S. Simulation of Growth Trajectories of Childhood Obesity into Adulthood. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017; 377(22): 2145-2153.

-

ACHI, Arkansas Medicaid. Comorbid Conditions and Medicaid Costs Associated with Childhood Obesity in Arkansas. 2019.

-

Alkon A, Crowley AA, Neelon SE, Hill S, Pan Y, Nguyen V, Rose R, Savage E, Forestieri N, Shipman L, Kotch JB. Nutrition and physical activity randomized control trial in child care centers improves knowledge, policies, and children’s body mass index. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:215.

-

Arkansas Department of Human Services, Division of Child Care and Early Childhood Education, Child Care Facilities Database. Unpublished data. 2020.

-

Kenney E, Cradock A, Resch S, Giles C, Gortmaker S. The Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions for Reducing Obesity among Young Children through Healthy Eating, Physical Activity, and Screen Time. Durham, NC: Healthy Eating Research; 2019. Available at: http://healthyeatingresearch.org

-

Gortmaker SL, Wang YC, Long MW, Giles CM, Ward ZJ, Barrett JL, …Cradock, AL. Three interventions that reduce childhood obesity are projected to save more than they cost to implement. Health Affairs. 2015; 34(11), 1932–1939.

-

Morrisey T. The Effects of Early Care And Education on Children’s Health. Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. 2019

Suggested Citation:Adams B, Sutphin B, Betancourt K, Balamurugan A, Kim H, Bolton A, Barrett J, Reiner J, Cradock AL. Arkansas: Creating Healthier Child Care Environments: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) in the Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS) {Issue Brief}. Arkansas Department of Health, Little Rock, AR, and the CHOICES Learning Collaborative Partnership at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; May 2021. For more information, please visit www.choicesproject.org |

The design for this brief and its graphics were developed by Molly Garrone, MA and partners at Burness.

This issue brief was developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in collaboration with the Arkansas Department of Health through participation in the Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES) Learning Collaborative Partnership. This brief is intended for educational use only. This work is supported by The JPB Foundation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders.