The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose.

Overview

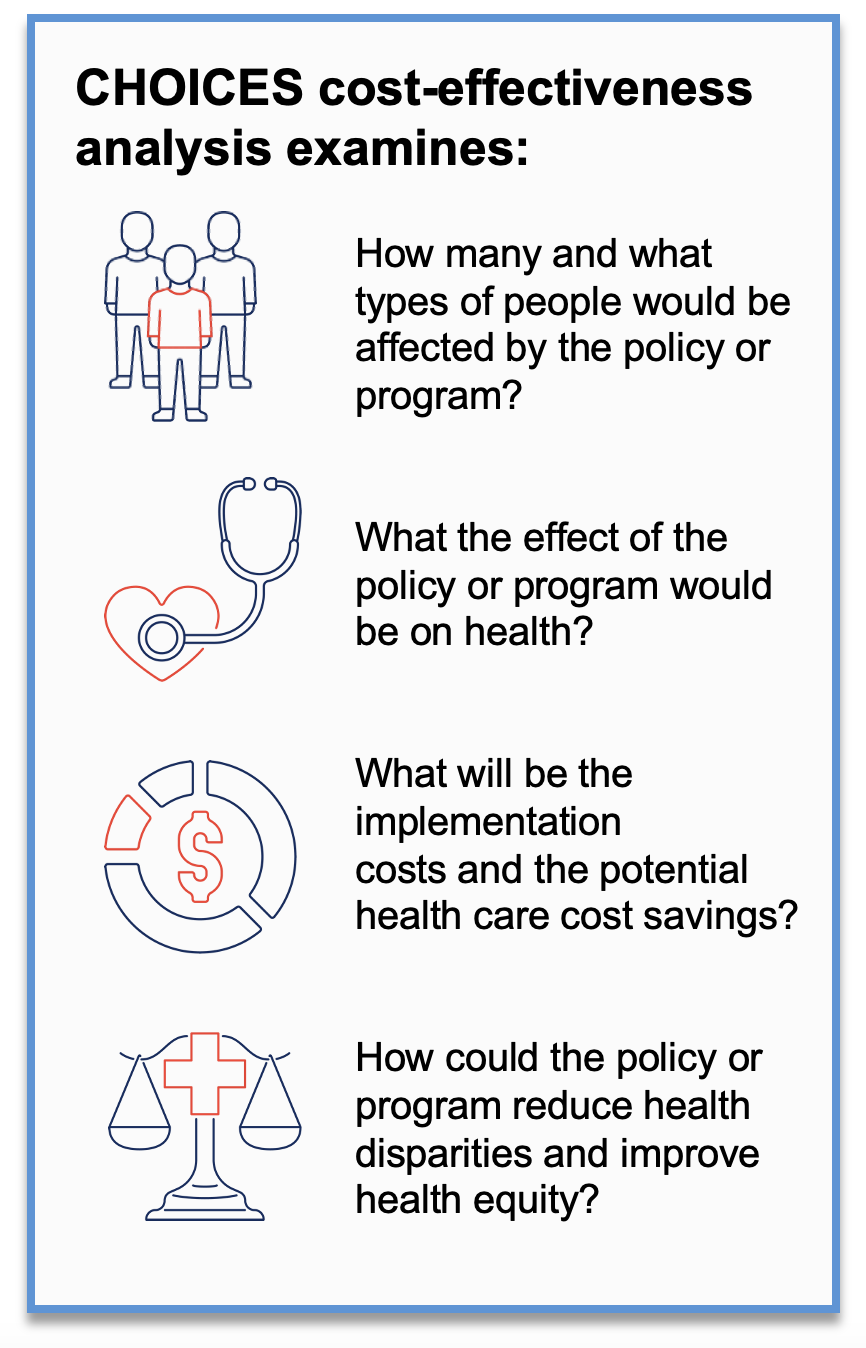

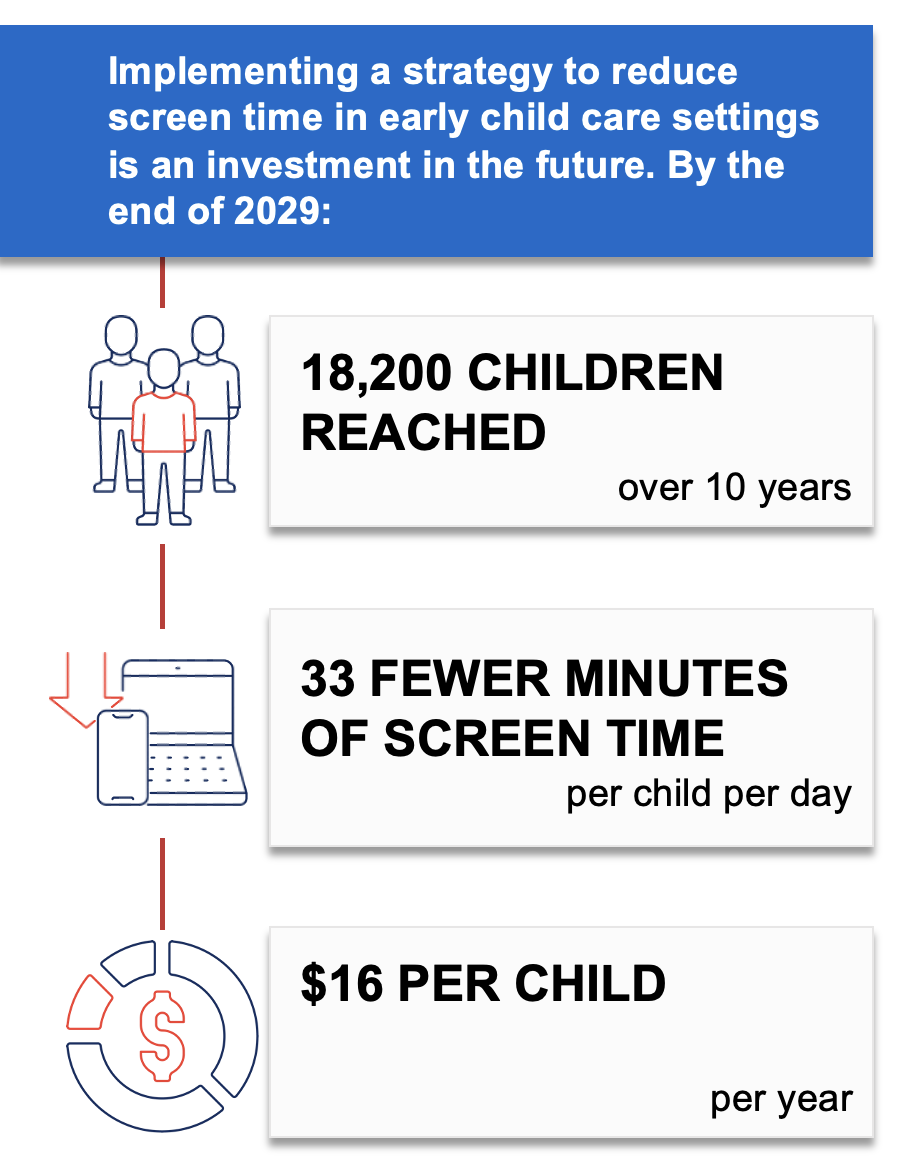

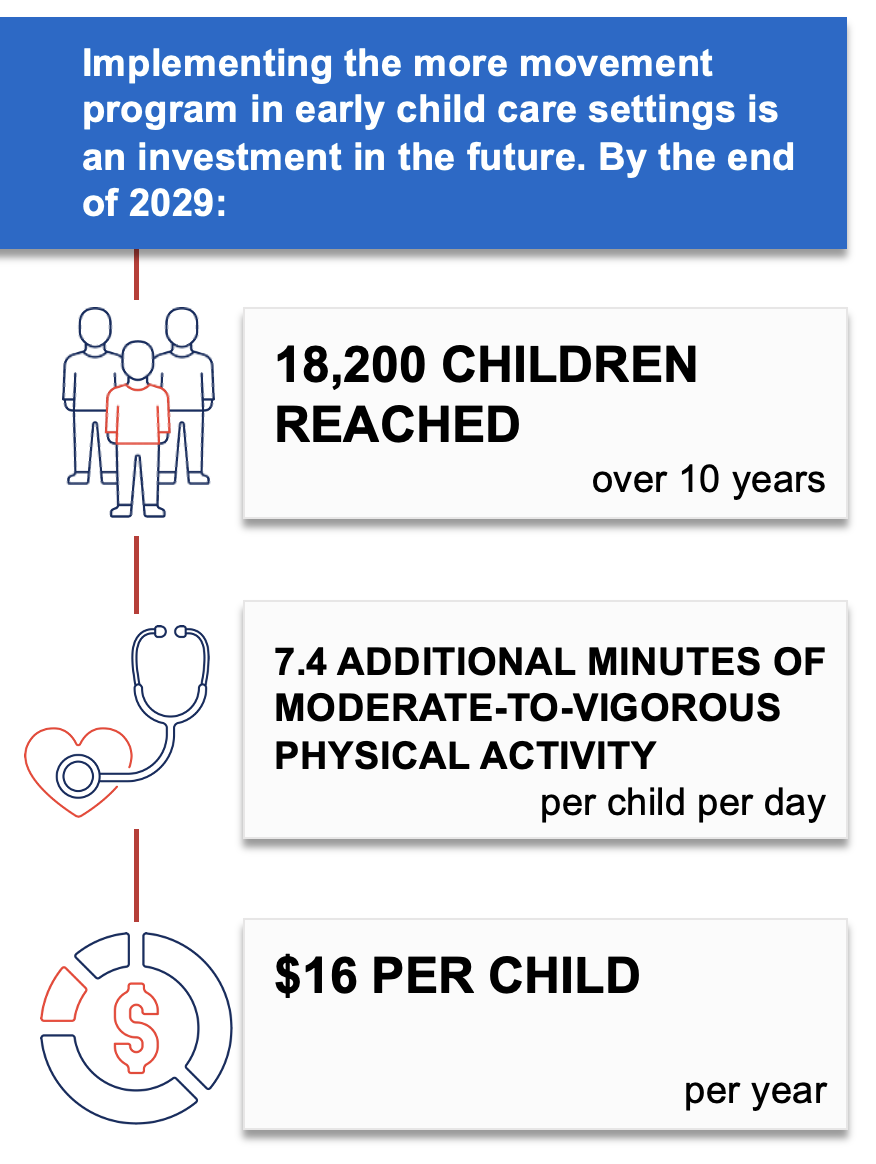

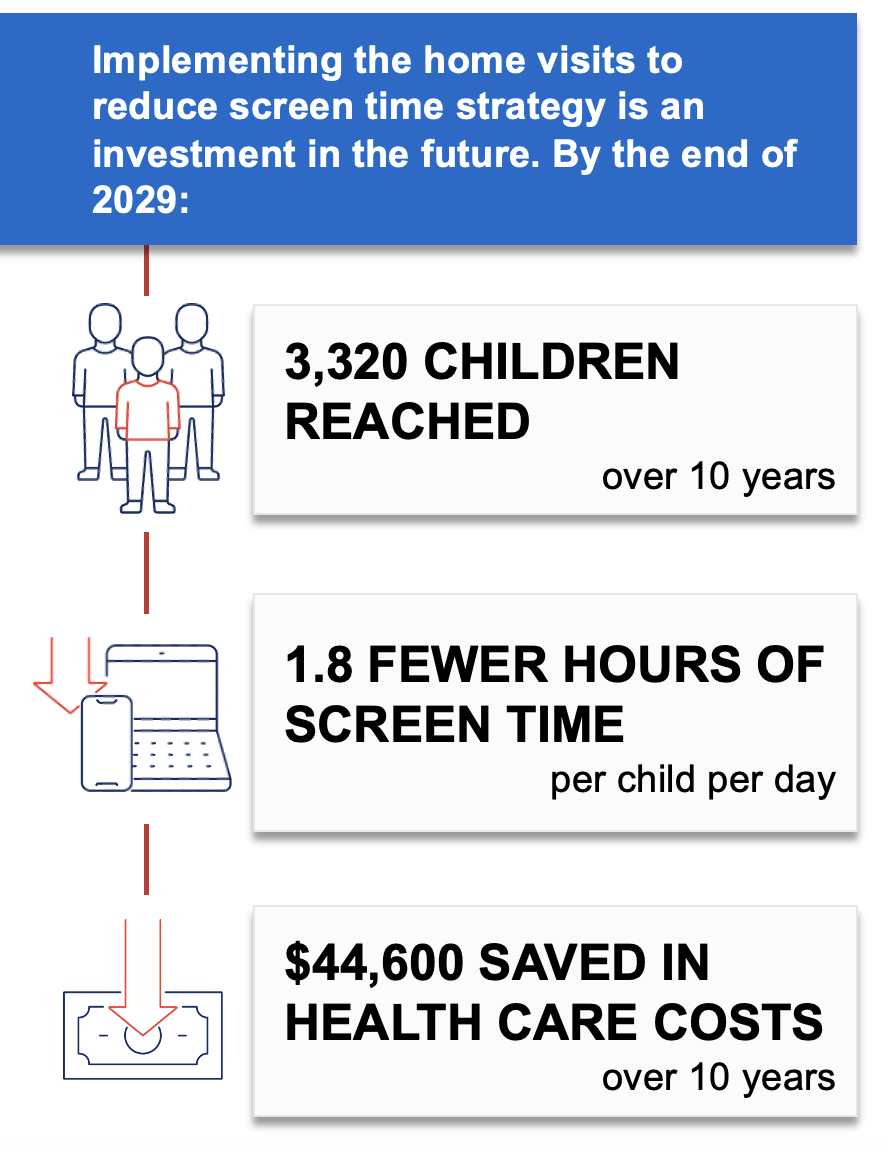

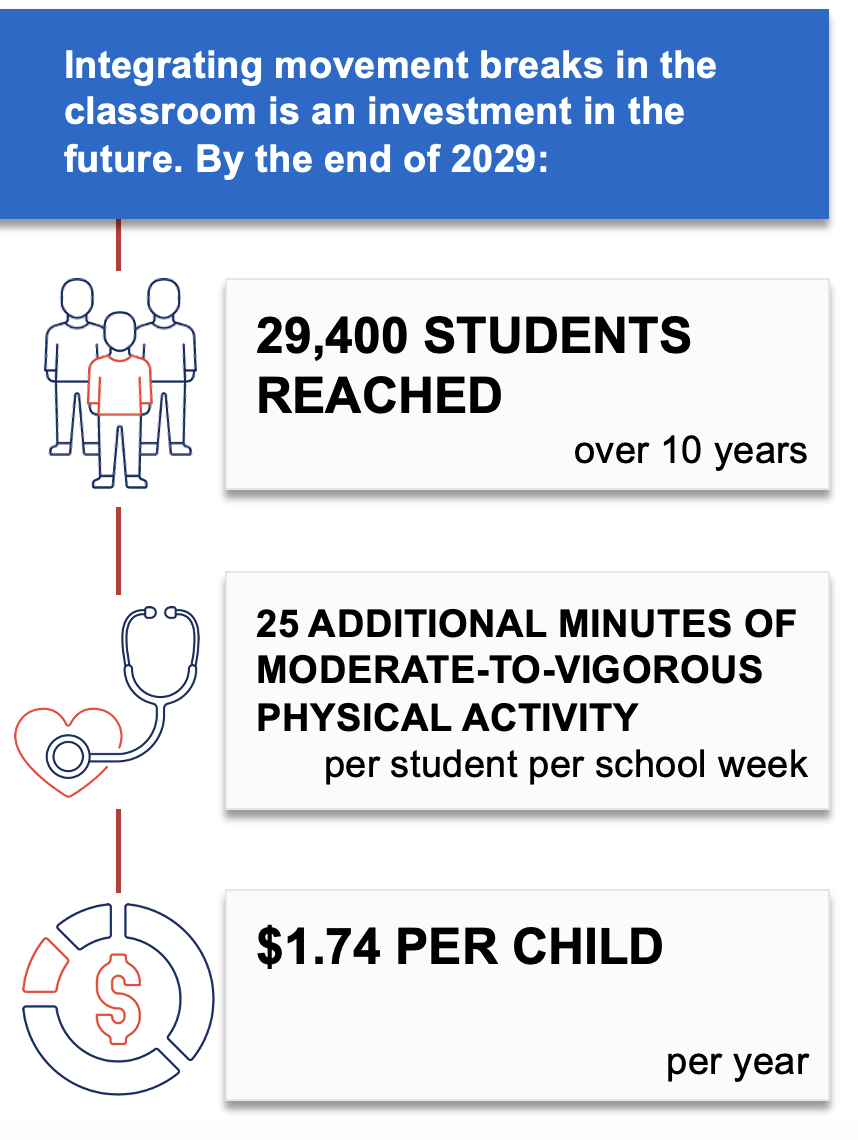

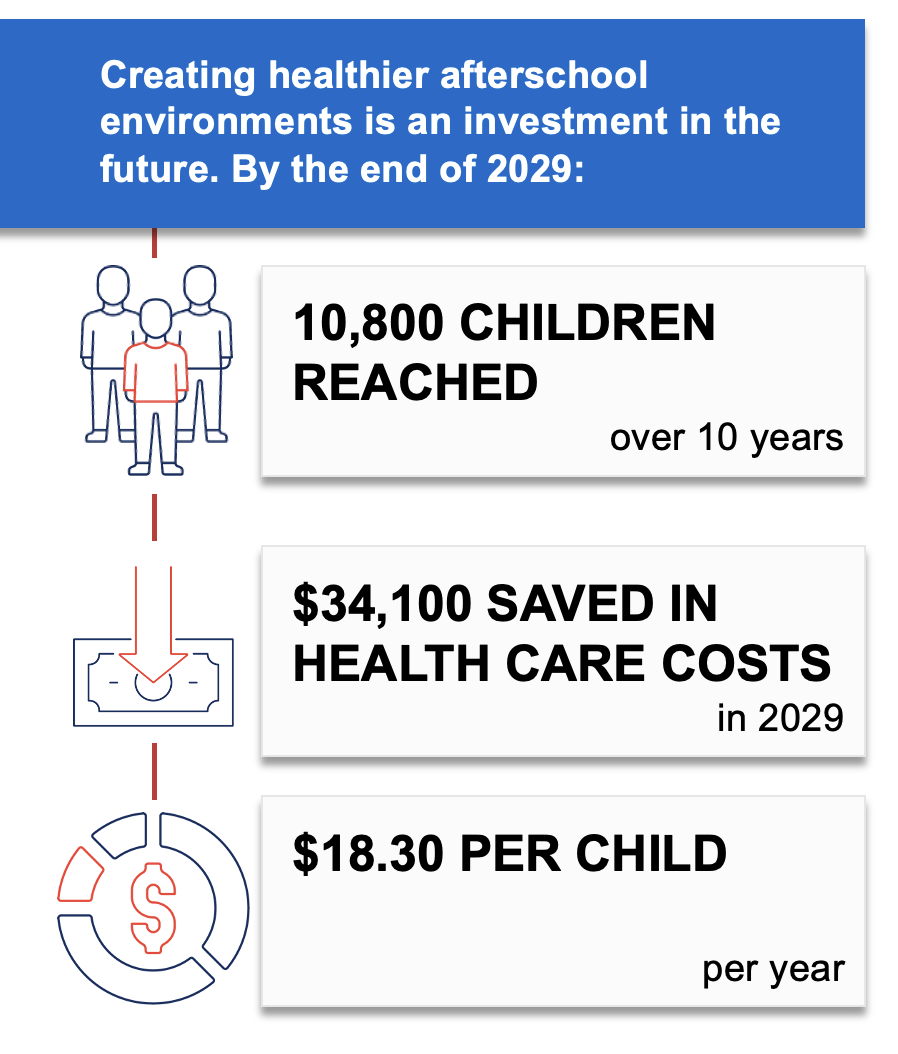

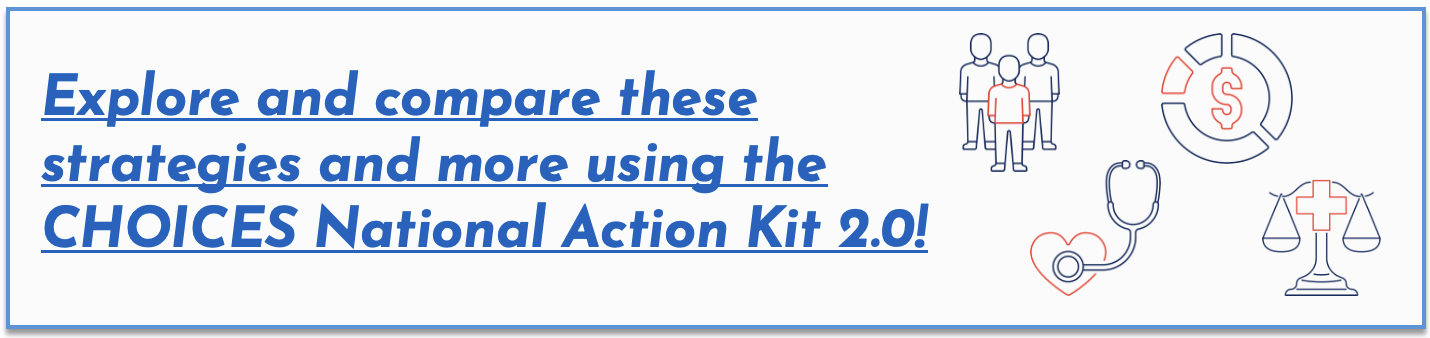

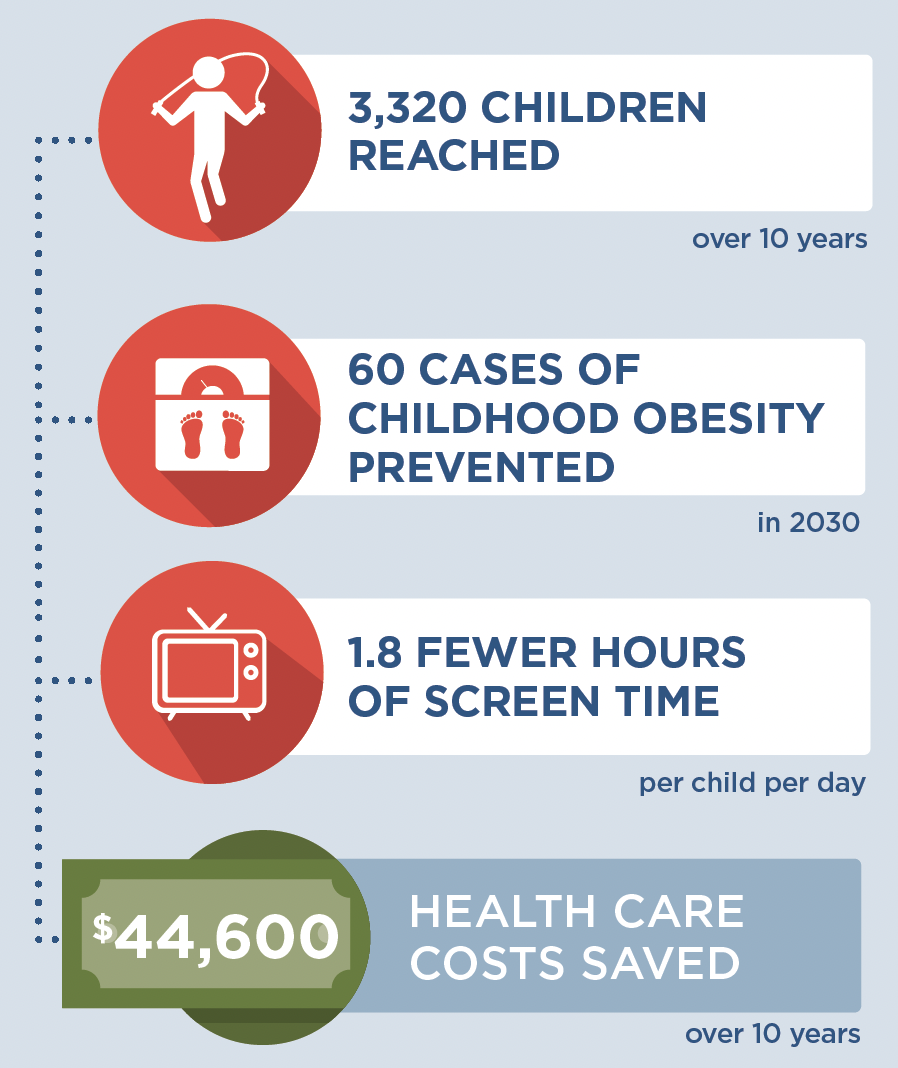

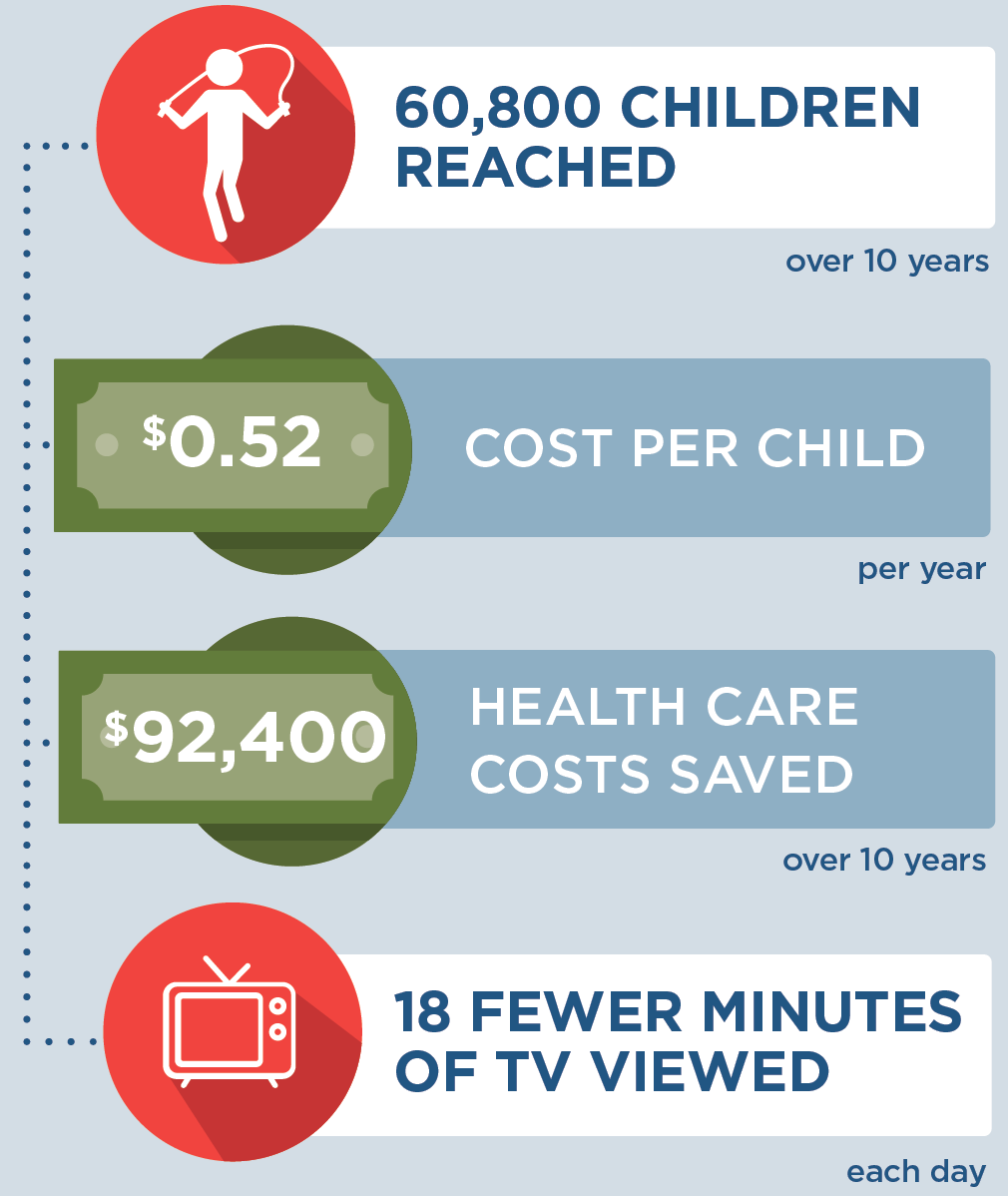

CHOICES uses cost-effectiveness analysis to compare the costs and outcomes of different policies and programs promoting improved nutrition or increased physical activity in schools, early care and education and out-of-school settings, communities, and clinics. This strategy report describes the projected national population reach, impact on health and health equity, implementation costs, and cost-effectiveness for an effective strategy to improve child health. This information can help inform decision-making around promoting healthy weight. To explore and compare additional strategies, visit the CHOICES National Action Kit 2.0.

Continue reading in the full report.

Contact choicesproject@hsph.harvard.edu for an accessible version of this report.

Suggested Citation

CHOICES National Action Kit: Electronic Decision Support for Pediatric Medical Providers Strategy Report. CHOICES Project Team at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; December 2023.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following members of the CHOICES Project team for their contributions: Molly Garrone, Banapsha Rahman, Ya Xuan Sun, Shilpi Agarwal, Ana Paula Bonner Septien, Jenny Reiner, Matt Lee, Zach Ward.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01HL146625), The JPB Foundation, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006376). The findings and conclusions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funders. The information provided here is intended to be used for educational purposes. Links to other resources and websites are intended to provide additional information aligned with this educational purpose

For further information, contact choicesproject@hsph.harvard.edu